Written by: Ashra Londa

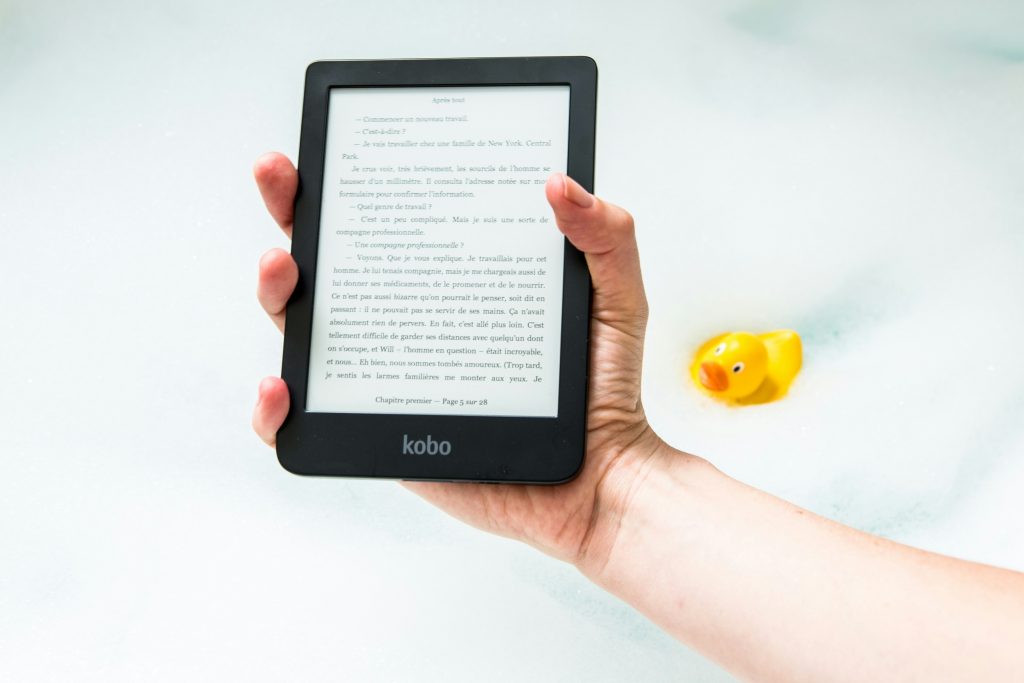

In the past 20 years, technology has begun playing a bigger and bigger role in how society functions on a global scale. Less and less are libraries used for finding books—and even if a patron still wants to read, they may rather sift through online options while perusing a tablet than check out a physical item. Databases and online articles have rapidly expanded in prospect and accessibility, while physical books shrink into smaller and smaller bookshelves.

On top of these changes, many people are no longer merely seeking reading materials from their local library, instead exploring the malleability between differing media formats and tastes (American Library Association 2023). Perhaps they are interested in borrowing a DVD of a film or television show. They may want to listen to a new audiobook. Perhaps they would rather stream a digital resource than stop by to pick one up. The media consumed by patrons has evolved into newer, more complex types: Film, audio, video games, and other multimedia options.

These changes may lead one to wonder: If people are less interested in reading, or have even stopped reading entirely, then does that mean they are no longer literate?

“Post-literate” is a relatively new term that started to see use in the 2010s. It is not defined as people who can’t read, but people who choose to gain information via non-reading means, such as audio, video, graphic, or gaming components (Massis, 2012). A post-literate society is not a dark age where once-literate, once-intelligent people have foregone reading for the sake of ignorance. In fact, America is still a society in which over 79% of its adult citizens are able to read and critically analyze their findings at a sufficient level (National Center for Education Statistics, 2019).

There are several ways in which post literacy has begun to shape how people interact with information outside of traditional reading. For example, people tend to read in smaller bursts, comprehending the most important components of what they scanned; this behavior can already be seen in the scholarly field, where many academics skim in order to pick up the main points of articles (Massis, 2012; Alberto Mora & Golovátina-Mora, 2020).

The movement toward digital, multimedia, and online engagement has also fundamentally shifted how libraries interact with their communities. Not only does post-literacy alter libraries’ practices, but it questions their very definitions, prompting librarians to redefine their functions into more relevant practices for their patrons. Post-literacy could even be understood as a complete retooling of the meaning of “literacy,” reconsidering the concept as a multimodal presentation of information rather than a single dimension (Alberto Mora & Golovátina-Mora, 2020).

A more library-relevant example of the multimodal post-literacy movement is embedded within the Metaverse, a platform based on the fusion of the physical and virtual realms (Noh, 2023). One such platform propelled libraries into the Metaverse: Second Life. This application allowed libraries to build virtual portals for anyone accessing the Internet to explore, framed as a series of hub worlds stocked with an information desk and a librarian’s avatar behind it. A vast number of libraries around the globe synced with the platform when it dropped in the late 2000s, giving virtual patrons a way to connect with libraries thousands of miles away from the comfort of their computer. While this particular Metaverse has fallen out of use due to the rise of budget cuts and the fading of the fad, it stands as a monument of what libraries could mean to patrons, as well as what post-literacy could yet transform libraries into.

It is impossible to document exactly how post-literacy will shape the world ahead of us. While aspects such as text skimming, multimodal information displays, and the Metaverse offer potential avenues, we are as likely to guess what could happen in the future as information science students were 50 years ago. Perhaps literacy will become completely unfathomable to today’s world; perhaps it will not be remembered, even “dismembered,” as a construct (Massis, 2012; Cline & López-McKnight, 2024).

I will sign off with this quote that ponders the state of the future, viewing the lens of literacy as a preconception that can be thought outside of:

“…We imagine outside the need for [Information Literacy (IL)] and its ways (and worlds) of knowing and learning and being (human) that it facilitates, mandates, and encloses. And this outside of IL, turns back around to demand just what to do about IL in the now to set in motion an after” (Cline & López-McKnight, 2024).

References

Alberto Mora, R. & Golovátina-Mora, P. (2020). Video composition as multimodal writing: Rethinking the essay as post-literacy. KnE Social Sciences, 4(13), 4-12. https://doi.org/10.18502/kss.v4i13.7690

American Library Association (2023, November 1). New ALA report: Gen Z & millennials are visiting the library & prefer print books. https://www.ala.org/news/2019/12/new-ala-report-gen-z-millennials-are-visiting-library-prefer-print-books

Cline, N. & López-McKnight, J. R. (2024). Before information literacy: Field notes on the end of IL. Journal of Information Literacy, 18(1), 5-13. https://doi.org/10.11645/18.1.568

Massis, B. E. (2012). Post-literacy and the library. New Library World, 113(5), 300-303. https://doi.org/10.1108/03074801211226382

National Center for Education Statistics (2019, July). Adult literacy in the United States. https://nces.ed.gov/pubs2019/2019179/index.asp

Noh, Y. (2023). A study on the developmental direction of the metaverse libraries for the future. Libri, 73(3), 239-252. https://doi.org/10.1515/libri-2022-0060

Leave a Reply