About zines

In the realm of publishing, the Xerox copier doesn’t get (ahem) a lot of press. This simple workhorse pales in comparison to the industrial machines used by major printing presses. Today, for those interested in self-publishing, the internet provides a handy medium for their desired content in the form of blogs and private websites. Flash back to the days before the internet, however, when communities whose numbers or interests couldn’t find mass-market appeal with print publishers, and the copy machine begins to show its true power as a medium for custom content within local, niche communities. Thus, the “zine” (pronounced “zeen”) was born: small, self-published, low-tech compilations of text and images.

Zines appealed especially to punk communities in the 1970’s, but that appeal applied just as much to queer communities, who felt the need to find and exercise a voice. Enabled by the advent of cheap photocopying, zines usually intended only a small circulation, and their creators gave them out free of charge or very cheaply. Experimental, fragmentary, sometimes even crude, these publications represent the social and economic margins of knowledge production. Zines come about through a desire to express oneself and one’s ideas, not necessarily to make money. Unsurprisingly mainstream audiences would normally be indifferent (at best) or hostile (at worst) to the sex, sexuality, and gender focused content of a queer zine; to queer audiences, however, zines provided a means for carving out local communities and serving their interests.

About zines

In the realm of publishing, the Xerox copier doesn’t get (ahem) a lot of press. This simple workhorse pales in comparison to the industrial machines used by major printing presses. Today, for those interested in self-publishing, the internet provides a handy medium for their desired content in the form of blogs and private websites. Flash back to the days before the internet, however, when communities whose numbers or interests couldn’t find mass-market appeal with print publishers, and the copy machine begins to show its true power as a medium for custom content within local, niche communities. Thus, the “zine” (pronounced “zeen”) was born: small, self-published, low-tech compilations of text and images.

Zines appealed especially to punk communities in the 1970’s, but that appeal applied just as much to queer communities, who felt the need to find and exercise a voice. Enabled by the advent of cheap photocopying, zines usually intended only a small circulation, and their creators gave them out free of charge or very cheaply. Experimental, fragmentary, sometimes even crude, these publications represent the social and economic margins of knowledge production. Zines come about through a desire to express oneself and one’s ideas, not necessarily to make money. Unsurprisingly mainstream audiences would normally be indifferent (at best) or hostile (at worst) to the sex, sexuality, and gender focused content of a queer zine; to queer audiences, however, zines provided a means for carving out local communities and serving their interests.

What is it?

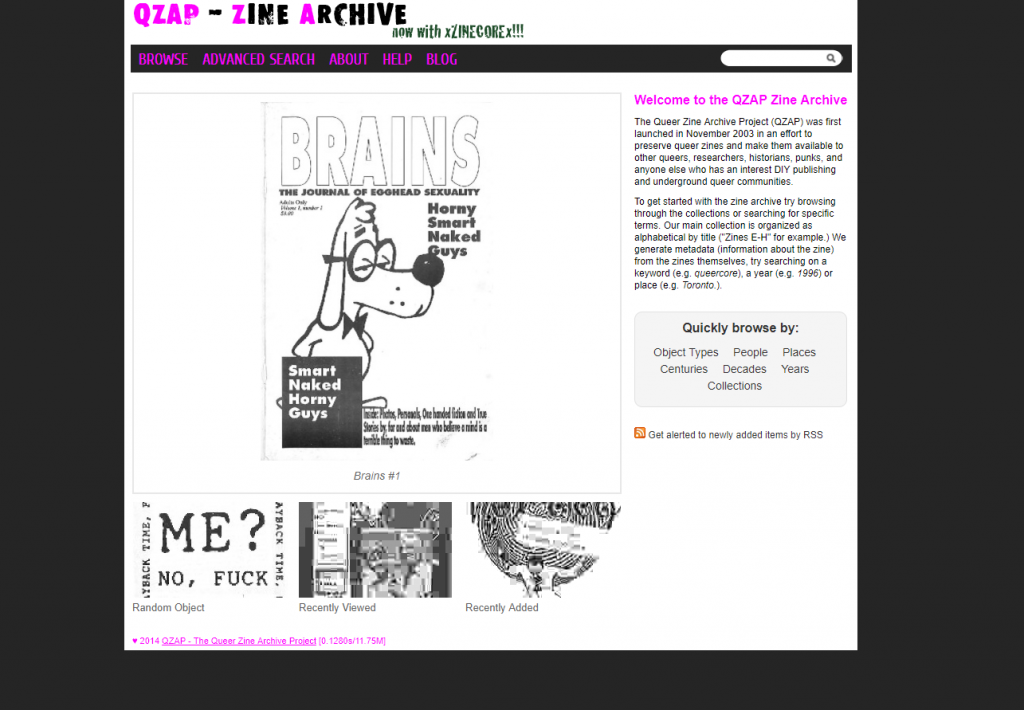

QZAP.org, the Queer Zine Archive Project, is an ongoing effort to find, digitize, and archive zines specifically related to queer communities. QZAP founders, Milwaukee-based Milo Miller and Christopher Wilde, met in the summer of 2001 while working with the organizing collective for Queeruption 3, an annual international Queercore festival. As various questions came up concerning gender, sexuality, race, accessibility, politics, and several other practical concerns, they found themselves referencing zines as guides to addressing those questions. In an email to me, Miller describes how they came to recognize the importance of zines as sources of information:

What is it?

QZAP.org, the Queer Zine Archive Project, is an ongoing effort to find, digitize, and archive zines specifically related to queer communities. QZAP founders, Milwaukee-based Milo Miller and Christopher Wilde, met in the summer of 2001 while working with the organizing collective for Queeruption 3, an annual international Queercore festival. As various questions came up concerning gender, sexuality, race, accessibility, politics, and several other practical concerns, they found themselves referencing zines as guides to addressing those questions. In an email to me, Miller describes how they came to recognize the importance of zines as sources of information:

Chris and I would look at each other and say, ‘Didn’t so-and-so write about that in their zine?’ and we’d then go through our personal collections to see if we could find the pieces. So we knew that we had a great wealth of information and stories within the zines in our collections, and then it became a question of how to share them.Miller and Wilde launched QZAP two years later. According to the “About QZAP” page, “The Queer Zine Archive Project (QZAP) was first launched in November 2003 in an effort to preserve queer zines and make them available to other queers, researchers, historians, punks, and anyone else who has an interest DIY publishing and underground queer communities.” The website consists of a blog-form feed and a database of categorized and searchable archived zines. Each zine is viewable as an embedded document within a scrollable, zoomable frame, and each is downloadable in PDF format. Topics range from queer punk music, queer culture, short stories, poetry, politics, to art, gender, and sex, to name a few. The authors and their intended audiences did not intend to produce or consume content considered “appropriate” for a mass market so the content, language, and images are largely NSFW. As an archive, QZAP seeks to provide a living history of queer culture and its respective interests, challenges, and expressions. Queer zines embody a unique source of data for that history. In Miller’s words, “The zines in our collection talk about sex and drugs and rock-and-roll and mental health, illness and wellness, health in general, racism, sexism, anti-gay bigotry and violence, pop culture, politics and activism and almost anything that one can think of, but through a lens that is often missed by other LGBTQ+ and straight publications and media.” Their fragmentary, frenetic character gives them the ability to reflect an impressively wide range of historical data, and their niche interests give us an intimate peak into the experiences and worldviews of those involved in creating and consuming them. This content ranges from frivolous and smutty to political, heartfelt, and hard-hitting, many of which address issues still relevant to queer communities today. Miller explains,

I think that queer zines are important because queer people are important and our lives and hystories are important. Zines are a tool (and an art, a craft, and to some degree community or subculture) to tell of our lives and focus on issues that affect us. They’re stories that don’t get told or presented in the same ways elsewhere.

The archive homepage features links to search fields and previews of newly archived zines.

The archive’s Advanced Search page with search fields

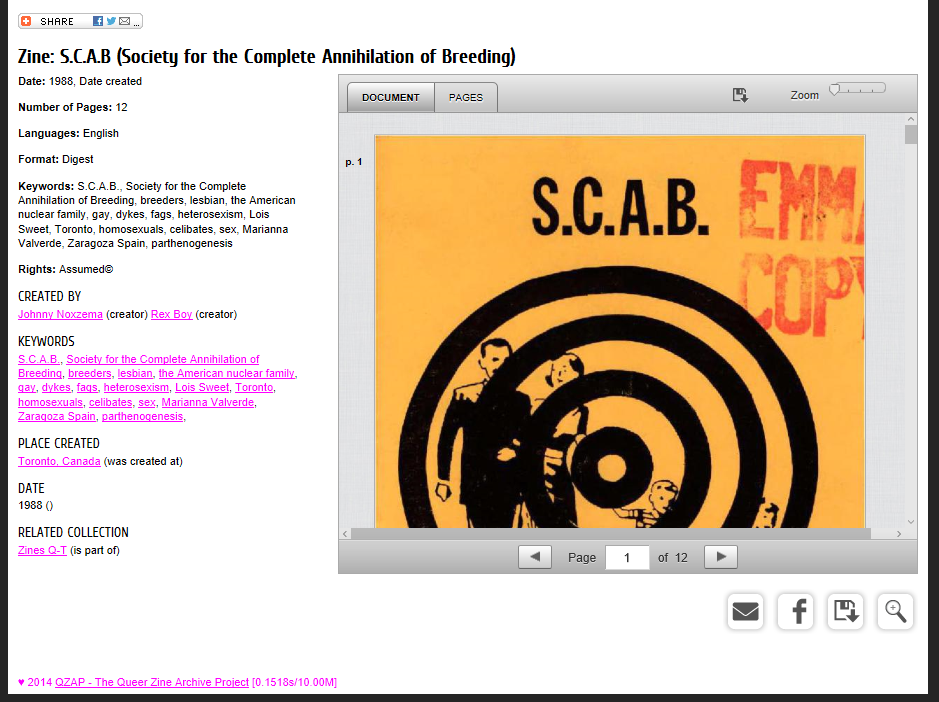

Example of a page featuring a zine. The window allows for the zine to be viewed, scrolled, and downloaded, as well as listing related zines, keywords, and metadata.

The mission of the Queer Zine Archive Project (QZAP) is to establish a “living history” archive of past and present queer zines and to encourage current and emerging zine publishers to continue to create. In curating such a unique aspect of culture, we value a collectivist approach that respects the diversity of experiences that fall under the heading “queer.” The primary function of QZAP is to provide a free on-line searchable database of the collection with links allowing users to download electronic copies of zines. By providing access to the historical canon of queer zines we hope to make them more accessible to diverse communities and reach wider audiences.At the start of the archive, QZAP had fifteen zines. To date, they have closer to 500 – and over 1,300 awaiting digitization, with six active people working on the project. QZAP relies on donations for zines and overhead costs, and sells a modest selection of merchandise. In addition to zines, the archive contains numerous examples of miscellaneous pamphlets and fliers, some of them uncredited. What you’d need to know The challenge in building this archive in particular is taking an aggressively analog medium and preserving it through digital means. The particular challenges faced by QZAP are in archive cataloging and publication and developing metadata standards for a union catalog. To build their archive, QZAP utilizes Joomla for their CMS/Blog and Collective Access for the archive itself. QZAP utilizes a DublinCore-inspired metadata standard known as Zinecore (Miller even composed an entire zine for Zinecore itself). The overriding concern is to make the archive searchable and shareable between multiple institutions–Miller explains that they’ve dabbled with Omeka for this purpose. If your project features zines, media similar to zines, or custom cataloging and archiving and you want to learn more about archiving, organizing, and sharing it with other institutions, take some time to explore these platforms and tools: Collective Access is a cataloging software that allows for building a catalogue with special needs without the use of customized programming. Omeka, an alternative, is a free, open-source web-publishing platform for museum, library, archival, and scholarly exhibitions. Joomla! is a content management system (CMS) used for building custom websites and online applications. Zinecore is a metadata standard developed by the Zine Librarians Interest Group for zines specifically for cross-institutional searching and sharability. The format for Zinecore is as follows:

| xZINECOREx Element | Actual Metadata |

|---|---|

| Title | Heavy Mayo |

| Creator | Milo Miller |

| Subject/Genre | Food/Cookzine |

| Publisher | Milo Miller |

| Contributors | n/a |

| Date of publication | 2009 |

| Physical description | 4.25″ x 7″, cardstock, 16 pages |

| Union ID | n/a |

| Language(s) | En – English |

| Place of publication | Milwaukee, WI |

| See also | SoyBoi, Mutate Zine, etc. |

| Freedoms and restrictions | Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 |

Leave a Reply