Dallas Independent School District, February 15 1994. Report to the Court of the Dallas Independent School District. Brenda Fields Dallas Schools Desegregation Collection (AR0833), University of North Texas Special Collections.

School hasn’t been out for long, but many North Texas parents already can’t wait for summer vacation to be over. While the youth of today may be more likely to play video games than engage in outdoor shenanigans, they are also more likely to take part in interracial friendships than the Dallas children of prior generations. Segregation was a part of the Dallas Independent School District (DISD) for decades after such practices were banned nationwide, ensuring that neighborhoods and relationships were predominantly single-race. Our educational system may not be perfect, but at least all of our students can be educated together.

In 1954, the Supreme Court ruled in Brown v. Board of Education that segregated schools were “inherently unequal.” Oliver Brown, the plaintiff, claimed that segregation brought about lower academic achievement, as well as the self-esteem of black students. This was deemed especially harmful in a society where education is such an essential aspect of a citizen’s life. Headed by Chief Justice Earl Warren, the Court ordered the states to integrate their schools “with all deliberate speed.”

But Dallas, like many other cities across the nation, decided to take its time. During the 1956-57 school year, DISD was still segregated. In this news clip from the KXAS-NBC 5 News Collection, President of the Board of Education, Dr. Edwin L. Rippy, cites an insufficient amount of planning time for not integrating. The accompanying script states that the NAACP called for a hearing about the integration issue before the start of the school year, September 5th, but Judge Atwell would not set a hearing date until after calling his docket on September 10th, making the hearing almost pointless.

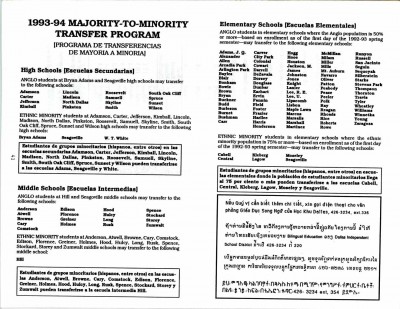

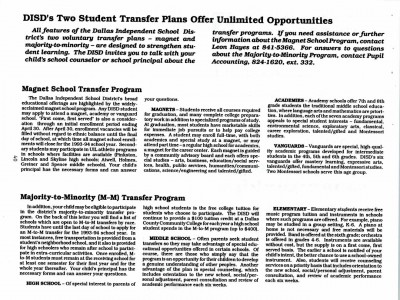

In October of 1970, the court case Tasby v. Estes was initiated. Judge William Taylor declared the district to be operating under dual school systems.He ordered the district to integrate through busing, which shook up neighborhoods by pulling students from one part of town to another. Though it was a step forward, busing upset whites and blacks alike. Throughout the next several years, the district worked to establish better methods of integration. Magnet schools were created, where students of all races could complete rigorous college preparatory work, as well as learn real world skills through a Career Center. The district also implemented its Majority-to-Minority Transfer program, in which students had the option of transferring to a different school to diversify the population. In 1994, Judge Barefoot Sanders declared Dallas desegregated. The Tasby case was finally dismissed in 2003.

Dallas Independent School District, February 15 1994. Report to the Court of the Dallas Independent School District. Brenda Fields Dallas Schools Desegregation Collection (AR0833) University of North Texas Special Collections.

Brenda Fields is an activist for educational equality in the Dallas area. For 15 years, she served as the Chairwoman of the NAACP’s Educational Committee, and she also became president of the organization. Fields became involved with DISD in 1975 when she tutored children through the district’s Adopt-A-School program. During this time, she was appointed to the African American Advisory Committee to the Superintendent. Fields served as a co-plaintiff in the Tasby v. Estes case.

The materials in the Brenda Fields Dallas Schools Desegregation Collection offer a view of the changing educational landscape in North Texas following the Tasby v. Estes case, but desegregation also had lasting effects on the makeup of Dallas neighborhoods, in terms of race, culture, and industry. Information about the city’s changing borders and community needs can be gleaned from this collection’s court reports. Six VHS recordings of NAACP public meetings concerning parental involvement in schools are another exciting inclusion of this collection.

-by Alexandra Traxinger Schütz

Leave a Reply