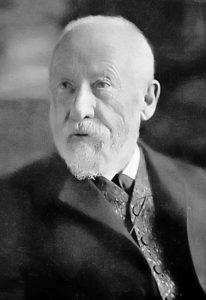

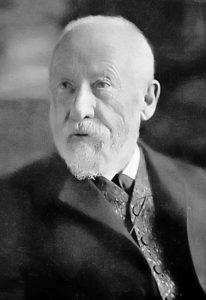

Wilhelm Dilthey, 1833-1911, German philosopher. Sought to apply the rigor of Kant’s philosophy to human experience. Made significant and lasting contributions to history, hermeneutics, and empirical philosophy.

Photo of women working in a 19th century factory during the Industrial Revolution. The mechanized, routinized, impersonalized labor depicted serves as an illustration for the rationale behind reactions against the Natural Sciences and their worldview.

The Lady of Shallott, John William Waterhouse (1888), depicting a scene from an Alfred Lord Tennyson poem of the same name, highlights the vision of Romanticism and its view of the human subject in light of the depersonalized Industrial forces of the same era.

Leave a Reply