In 1961, the Amon Carter Museum of Western Art opened its doors in Fort Worth, Texas. Plans for a museum were left in the will of Amon G. Carter, Sr., who passed away in 1955 after suffering several strokes. His acquisitions, including the work of Charles M. Russell and Frederic Remington, would become part of the museum’s holdings. The Amon G. Carter Foundation, established in the summer of 1945, took on the task of establishing Carter’s vision for a public museum of American art. His daughter, Ruth Carter Stevenson, was especially involved in this endeavor.

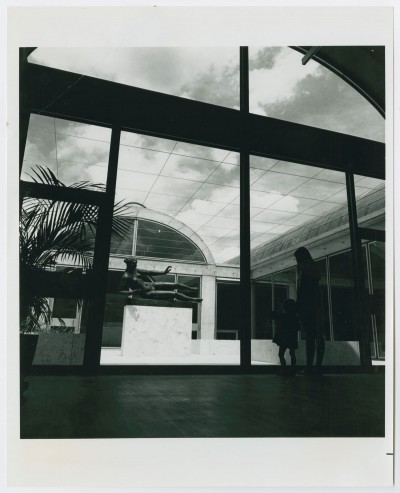

In 1959, the city of Fort Worth donated a parcel of land downtown to the Foundation, so that construction on the museum could begin. Philip Johnson designed the building with Texas shell-stone, and used bronze and teak in the interior of the museum. The museum was completed and open to the public in 1961, and an expansion was completed two years later, providing the facility with a basement, a storage vault, and more ground-level exhibition space.

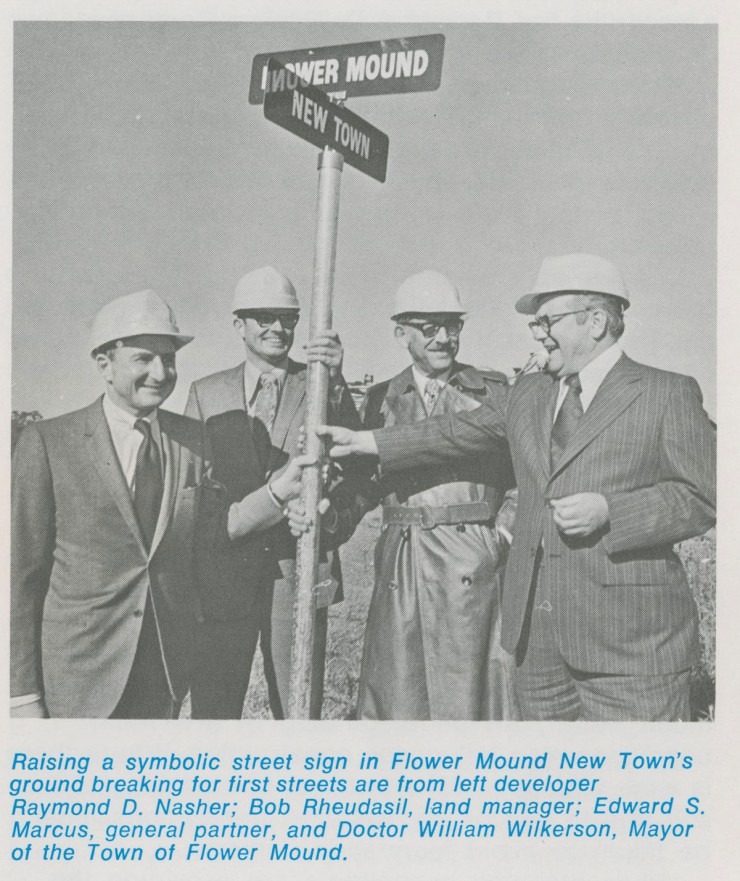

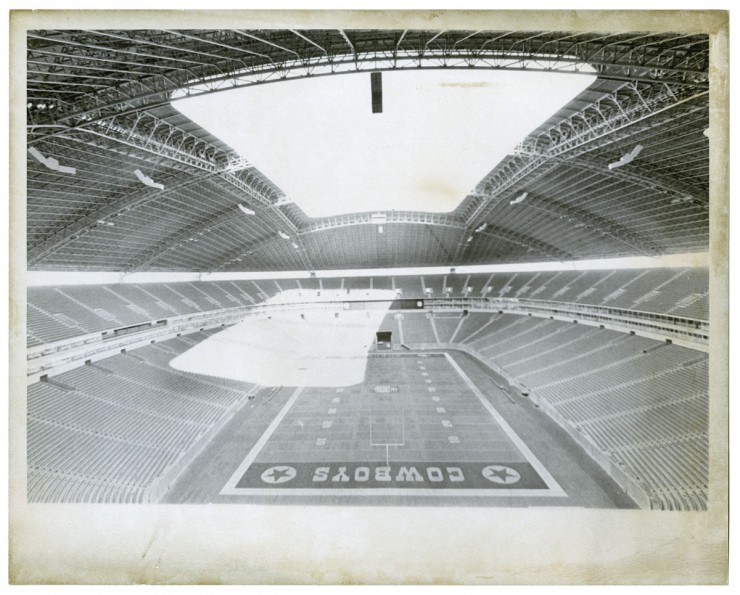

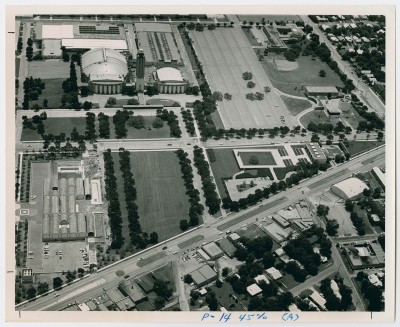

Aerial view of the Kimbell Art Museum (bottom left), Will Rogers Memorial Center & Coliseum (top left), Fort Worth Community Arts Center (top right), and the Amon Carter Museum of American Art (right middle, below the Fort Worth Community Arts Center, UNTA_AR0327-023-003

The holdings of the museum are unique and inspiring. Rather than focusing on regional artwork, the “western” art at the museum portrays the powerful need of Americans to continually move westward. The excitement of the frontier, as well as the sense of it diminishing with American expansion, is prevalent in the work at the Amon Carter.

The museum quickly rose to national acclaim, and the Carter Foundation continued to utilize the museum in its mission to educate the city of Fort Worth and enrich the community. In 1966, the museum received a $30,000 grant from the National Foundation of Arts and Humanities to focus on education. The museum received the same grant in 1969. The museum used this grant to research how museums and educational institutions can cooperate together to supply a fulfilling learning experience for children. In 1977, 36,000 square feet were added to the museum, including a larger library and a movie theater.

The Amon Carter museum celebrated its 50th anniversary in 2011. As part of its anniversary campaign, the museum decided to change its name to the “Amon Carter Museum of American Art.” The museum continues to excite, entertain, and educate residents of the Dallas-Fort Worth Metroplex with its collection. To learn more about the Amon Carter museum’s holdings and other endeavors, view their webpage here.

The photographs of the Amon Carter Museum of Western Art come from the Lester Strother Texas Metro Magazine collection. The Texas Metro was largely founded to publicize the Dallas-Fort Worth Airport and the many economic opportunities in the Southwest Metroplex. The collection includes 183 linear feet of articles and photographs from the magazine, as well as other grey literature.