In addition to its strengths in jazz and western art (i.e. classical) music, UNT’s College of Music also boasts one of the country’s largest early music programs. For the uninitiated, early music in this context refers to the study and practice of historical performance techniques, using primary (treatises, contemporary accounts, original manuscripts and editions) and secondary (scholarly studies and analyses) resources. The discipline grew out of post-World War II musicology and its positivistic emphasis on discovering “new” composers and works from the Baroque era (1600-1750) and earlier, with an initial interest in authenticity that was later deconstructed in the 1980s to become simply another way of performing classical music, normally using original or facsimile instruments: gut strings, early bows, harpsichords instead of pianos, etc. A common name for this type of ensemble is Collegium Musicum, a musical society that appeared in German areas during the Reformation.

One of the earliest instances of a Collegium at North Texas appears to be this concert from July 1953 presenting “a program of rarely-heard music” (Renaissance- and Baroque-era French and German works) and including an appearance from stalwart trumpet professor John Haynie, who joined the faculty in 1950 and would continue for forty years (Haynie died in 2014). The cover for the book of concert programs from 1952-1953 also appears to be an ensemble of students in period costume near a harpsichord, further confirming the rising interest in historical matters at the (then) School of Music.

In the late 1950s, a doctoral musicology student named James Kenton Parton directed performances by the Collegium Musicum “Pro Musica Antiqua”, as evidenced by this 1959 article in The Campus Chat and this 1960 concert program featuring an impressive variety of compositions spanning the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Parton’s dissertation Cantus Firmus Techniques and the Rhythmic Elements of Style in the Organ Music of the Early Tudor Era was published four years later; he was also active as an arranger of early music and a composer in his own right.

Of course, vocal and choral music also received due attention, beginning in at least 1949 with the excellent Madrigal Singers under the direction of Robert Ottman; the use of the term “madrigal singers” appears to have been more all-inclusive in regard to genre and period, hence Fauré and Brahms were performed as much as Vittoria and Purcell. However, this likely served as a foundation for later efforts like this Collegium concert of medieval and Renaissance music directed by Samuel Adler and Chamber Chorale performances of Renaissance-era choral music from the New World, conducted by Lester Brothers. These eventually led to the establishment of the Canticum Novum choir (directed for around thirty years by Henry Gibbons) and the Collegium Singers, currently conducted by Richard Sparks.

Following his graduation from the University of Iowa in 1963 (dissertation: The Theory and Practice of the Monochord), Cecil Adkins joined the North Texas School of Music faculty and promptly founded a program for the study of early music. Some of the first major performances were marionette operas, following an eighteenth-century tradition; a 1967 production of Haydn’s Philemon und Baucis was toured extensively throughout the Midwest. Music Reference Librarian Donna Arnold remembers participating in a similarly-toured later production of Pleyel’s Die Fee Urgele, specifically that Collegium students made the papier-mâché marionettes themselves, using pink toilet paper and wallpaper paste.

Adkins was a man of myriad talents: in addition to directing the Collegium, he prepared many of the editions from which they performed (often subsequently publishing them) and even built instruments for the Collegium when they could not be purchased. He and his wife Alis Dickinson co-edited the landmark publication Doctoral Dissertations in Musicology from 1967-1997, when the American Musicological Society decided to move the resource online; it is worth noting that North Texas faculty member Helen Hewitt (who was Kenneth Parton’s dissertation advisor) began the publication in 1952. Adkins’ interest in organology also encouraged him to specialize in several obscure instruments, perhaps most notably the tromba marina.

The 1970s saw Adkins’ edition of Orazio Vecchi’s madrigal comedy L’Amfiparnaso and its performance by the Western Wynde in New York City, as well as heightened participation in the Collegium (including the eldest children in the Adkins family). In 1982, one year before Adkins created Les Petits Violons (the first period-instrument Baroque orchestra in the Southwest), Lenora McCroskey joined the North Texas faculty from the Eastman School of Music as a harpsichordist and organist. She eventually became assistant director of the early music program and has remained a vital component of the Metroplex performance practice scene, even following her retirement in 2009.

After his appointment as Regents Professor in 1985, Adkins continued to serve on doctoral committees and further his work in both performance and scholarship; he retired in 2000, succeeded by lutenist Lyle Nordstrom. In Nordstrom’s decade as director of the early music program, he continued the tradition of excellence with recordings, tours, and multiple appearances at the Boston Early Music Festival. Upon his retirement in 2010, the program had become one of the nation’s largest, with several dedicated performance practice faculty and a well-deserved national reputation. Dutch recorder player and consummate musical editor Paul Leenhouts assumed directorship thereafter, and the program remains an essential and vibrant part of the College of Music, with several concerts each academic year, performances at festivals, and US premieres of obscure works.

Suffice to say that early music has been important at North Texas for at least sixty years, and it shows no signs of diminishing.

This post is dedicated to the memory of Cecil Adkins, who passed away in November 2015; special thanks to Elisabeth Adkins, Donna Arnold, and Linda Strube for their contributions.

— by Andrew Justice, Associate Head Music Librarian

- North Texas student members of the 1978 Collegium Musicum.

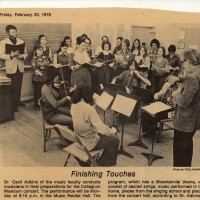

- Dr. Cecil Adkins of the music faculty conducts musicians in final preparations for the Collegium Musicum concert. Newspaper source unknown.

- Collegium Musicum students in the 1967 Yucca yearbook.

- Collegium Musicum students, circa 1950s.

- Former North Texas music professor Cecil Adkins, who founded a program for the study of early music.

Leave a Reply