This is a guest post, adapted from an essay commissioned by the UNT Art in Public Places Program.

1935 Mural represents a specific historic and cultural moment for the University of North Texas, known in 1935 as North Texas State Teachers College. The campus, then part of the rural community of Denton, was greatly impacted by the economic and political climate of the period, which was dominated by the economic crises known as The Great Depression. The mural portrays campus life in the 1930s from the perspective of North Texas students, and the style shows influence from the contemporary art movements of American Regionalism and Social Realism.

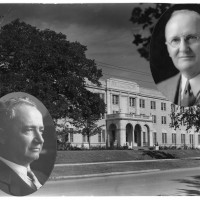

The Great Depression began with the Wall Street Market Crash in 1929 and had devastating effects across the globe.[i] While this did likely result in great personal hardship, and even an increase in State tuition in March of 1935, it also benefitted the college in a unique way.[ii] In response to The Great Depression, U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt and his administration created the New Deal program, which stemmed from economic theories and policies created in hopes of relieving a broken economic system.[iii] The New Deal distributed federal funds through a variety of public endeavors, including the Public Works Administration or the PWA, which was founded in 1933 and spent around “$4 billion in construction” on educational buildings across the nation.[iv] This Program funded seven new buildings on North Texas State Teachers College, including the first dormitory, Marquis Hall, where 1935 Mural originally hung.[v]

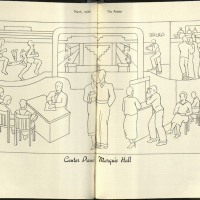

Completed in 1936, Marquis Hall housed 100 women students and featured “two large dining rooms, two banquet halls, a grill and a large reception room.”[vi] The creation of Marquis Hall, was an empowering step for women students. An all-female dorm allowed women to more easily convince their families to let them attend college, since this was considered safer and more proper housing for the period’s standards than previous accommodations in off campus boarding houses.[vii] Women are thus featured prominently in the mural, shown seated at the front of class, student teaching, learning alongside men, and participating in campus activities such as buying books and dancing. However, women are minimally represented in the graduation composition and are not shown participating in athletics. Women were not permitted to participate in inter-collegiate athletics and instead created teams in variety of sports that competed with one another through the college’s Women’s Athletic Association.[viii]

Despite such restrictions as well as strict curfews and rules of etiquette enforced by Hall Mothers in the new Marquis Hall dormitory, women still made their marks on campus, including with this mural. The mural was painted by two advanced painting classes over two semesters, directed by art professor Ronald Williams.[ix] In 1936, the Campus Chat newspaper reported 14 students, including 8 women, as having painted the mural.[x] The students were (as listed in the newspaper article): Frances Allred, Mildred Christie, Otis McMillen, Mary Sweet, Stephen Dickson, Joe Tom Meador, Marie Spiller, Pallie Brumbelow, Cleo Hendershott, Dorothy McMurtray, Marie Holland, J.L. Slack, Mackie Baswell, and Dorothy Gay.[xi] According to this article, it took 900 hours, or five and one-half months, and about forty-five pounds of oil-paint to complete the mural.[xii]

After its completion, 1935 Mural was installed in Marquis Hall behind the serving counter at The Grill.[xiii] The painting hung in The Grill until 1969 when the grill was no longer open to students.[xiv] In 1978, it was displayed in the former North Texas Historical Museum, until the museum closed in 1986, and it was then stored by University Archives.[xv] This was until alumnus Mary McCutcheon, who as a student had dined at The Grill, became the new director of Dining Services.[xvi] She fondly remembered the mural and requested it be hung in Bruce Hall cafeteria in 1988.[xvii] In 2013, the mural was temporarily removed while Bruce Cafeteria was expanded. It was cleaned and restored and returned to the cafeteria in 2017, alongside a new mural created in 2015, exactly 85 years later, titled Denton Shuffle. The timeline on the walls between the two murals describes how the campus developed from 1935-2015.

While many aspects of campus life have endured and are reflected in both murals, the campus has also undergone many changes through its growth over 85 years. The most obvious growth, aside from the campus’ physical footprint and myriad academic programs, is in our community diversity. At the time students painted 1935 Mural, during the height of The Great Depression, enrollment had decreased by more than half, to only 1800 students.[xviii] Though at its beginning in 1890, college enrollment included 28 Native Americans students, there is no record of Native American enrollment in the 1930s.[xix] The first known Hispanic student attended North Texas in the late 1930s and early 1940s,[xx] and the first African American student enrolled in 1954.[xxi] Thus, 1935 Mural serves as a literal snapshot of daily student life during a specific historical and cultural moment.

The left side of 1935 Mural focuses on North Texas State Teachers College’s emphasis on preparing the next generation of educators, which remains a UNT strength. The background is dominated by the beloved Education Building, which was built in 1918 and located on the now open lawn behind Sage Hall.[xxii] The Education Building was a central part of many students’ day to day lives and housed many departments before its demolition in 1979.[xxiii] In the foreground of the Education Building, children are instructed by a student teacher around a flowerbed of cannas. The year the mural was painted saw an expansion of the education program with new classes for training teacher-librarians[xxiv] and graduate courses added with “instant success in enrollment.”[xxv] The left side of the mural also depicts enduring parts of campus life, such as studying on the quad and walking to class with friends.

The middle section of the mural is framed by the stage of the auditorium building, which is still used for classes and events today. On the left side of the stage, the track team and football team practice, representing a successful decade of the college’s athletic history. In 1936 the college celebrated when Eagle halfback Johnny Stovall was selected as a member of the “Real All-American Team” in the magazine Sport Pictorial.[xxvi] The track team won national recognition in the 1930s under the leadership of Coach Choc Sportsman who lead North Texas track men to win seven Lone Star championships and hold the conference records in ten events.[xxvii]

Bellow the track runners, a professor lectures to three students, which represents a continuing part of campus life, but also the increasing standards for the faculty in the 1930s, who were holding higher degrees.[xxviii] On the right of the professor, in the middle foreground, a couple stands arm-in-arm, looking out past the viewer. The woman wears a yellow, 1930s-style dress, carrying books in one arm and escorted by a young man in a Talons Club sweater. Talons was one of several social clubs then on campus, as the Greek clubs did not begin until 1952.[xxix] Talons formed in 1927 with a mission to “bring about a closer fellowship among the boys, to arouse a stronger college spirit, and to support all college activities.”[xxx] A version of the Talons still exists today as a coed school spirit organization that was formally incorporated in 1960.[xxxi]

This central couple seems almost to walk away from the bookstore on their left, where other students wait in line to purchase textbooks. The campus did not have their own bookstore at the time, but instead students purchased books and supplies from Voertman’s Teachers College Store.[xxxii] Voertman’s opened on fry street in 1925.[xxxiii] It included a soda fountain and quickly became a popular hangout for students and important part of life in Denton.[xxxiv] This is possibly represented by the young man having a drink at the soda fountain on the upper right of the bookstore. One of the more unexpected depictions of student life in the mural, that in some ways has little changed, is the man on the phone to the right of the stage. He is likely using a community phone at a boarding house off campus, where all male students were housed during that year.

The far-right side of the mural shows students in graduation attire, posing as if for a picture. The Power Plant building, which has stood over campus since 1915, is shown in background.[xxxv] Despite a decrease in enrollment, the 1935 class was said to be the largest graduating class to date with 160 students graduating with either Bachelor of Science or Bachelor of Arts degrees.[xxxvi] In North Texas tradition, the class was photographed on bleachers near the Power Plant after the graduation ceremony.[xxxvii]

End of the year festivities would not be completed without the Yucca Yearbook, represented by the two blooming yucca plants in the bottom far-right corner of the mural. The yearbook was published under the title Yucca from 1907 until 1974.[xxxviii] The 1935 graduation celebrations also included the annual All-College Publications Dance, represented by the two couples dancing to a live band. The Yucca Queen, winner of the Yucca Yearbook’s Favorites competition was traditionally announced at the dance and in 1935 the winner was Mary Willis.[xxxix]

The mural’s depictions of students participating in activities like dancing and studying are not an accident, as this subject matter was greatly influenced by a prominent art movement of the period known as American Regionalism. Regionalism depicted and promoted traditional values through representational depictions of rural American daily life, and with these depictions was attempting to create a truly American art form, separate from European influenced Modernism.[xl] Well known Regionalists painters working during the period, often on New Deal funded public art, include Grant Wood, John Steuart Curry, and Thomas Hart Benton.

In 1935, Regionalist painter Grant Wood wrote an article stating that Regionalism was particularly well suited for government sponsored murals and voiced his hopes that university students, like those painting the mural here at North Texas, would play a large part in these public projects.[xli] Wood hoped that New Deal funded murals would foster the creation of a purely American art style and the “building up of an honestly art-conscious America.”[xlii] There is no proof that our 1935 Mural was funded through a New Deal program like the Public Works of Art Project (PWAP) founded in 1934.[xliii] However, we do know the building where it originally hung was funded through the New Deal program called the Public Works Administration.[xliv] The PWAP program allowed the broad circulation of the Regionalism’s subject matter and ideas, thus influencing artists across the nation, such as those that participated in painting 1935 Mural.

While American Regionalism influenced the mural’s subject matter, the mural’s stylized, simplified, and structured look was influenced by another major figure painting movement of the period called Social Realism. This movement was known for depicting urban conditions with politically left undertones.[xlv] Social Realism gained traction in Mexico in the 1920s and 1930s as artists sought to create a truly Mexican art form, following the Mexican Revolution of 1910.[xlvi] Mexican muralists, such as Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera, rejected academic naturalism because they felt this style upheld the values of the past, which led them to create stylized figures to convey the social conditions of their time.[xlvii]

The Mexican government’s push for public art that portrayed their heritage greatly influenced President Roosevelt’s creation of the Public Works of Art Program.[xlviii] Mexican muralists such as Diego Rivera even painted public murals in the United States, directly influencing American artists. He also directly influenced student and faculty artists on campus as color reproductions of Rivera’s murals were brought to North Texas State Teachers College in March of 1934.[xlix] The exhibition was sponsored by the Art Club, Kappa Alpha Lambda, and was displayed in the Manual Arts Building, less than a year before work on 1935 Mural began.[l]

Professor Ronald Williams and the students who worked with him did not adopt the leftist imagery of Rivera, but were influenced by his style. Rivera often used the geometry of architecture to frame and structure his large compositions. 1935 Mural’s artists utilized this strategy by balancing the large composition with campus landmarks, such as the Education Building on the upper-left corner and the Power Plant on the upper-right corner. The composition is anchored and organized around the Auditorium Building’s stage, which creates a frame around the focal point of the central couple and looks similar to the organization in Rivera’s Detroit Industry mural created between 1932 and 1933.[li]

Rivera had been influenced by cubism while studying in Europe, which is shown in his simplified and geometric treatment of the human figure in murals like Detroit Industry.[lii] This style is also shown in the treatment of the human figure in 1935 Mural. For example, in the graduation composition, each part of the students’ robes, faces, and hats are treated as separate shapes with minimal shading, that flattens the figure. This simplified, geometric style became popular during the 1930s, especially as Rivera’s fame continued to rise in the United States.

1935 Mural is very much a product of its time. It was influenced by Great Depression New Deal policies that supported architecture and art production during the 1930s. It shows the impact that Regionalism and Regionalist art theory, such as Grant Wood’s writings, had on U.S. artists and educational institutions, particularly in rural communities like Denton. Through its style, it also shows the impact of Mexican Muralism in the United States. 1935 Mural uses these influential 1930s art movements to capture a part of campus history that today allows us to see our participation in the world around us, our positive growth, and our enduring traditions.

— by Isabel Lee-Rosson, MA 2017

- This early photograph of Marquis Hall includes the superimposed portraits of President McConnell (right) and former president Marquis (left).

- Women’s Athletic Association pictured in 1935 yearbook

- Art Professor Ronald Williams instructing art students on mural painting for Marquis Hall Grill as depicted in the 1936 Bulletin.

- The Education Building housed the Demonstration School on the top floor and held college education classes on the floors below. This photo is undated.

- Coach Choc Sportsman watching a stop watch on the original track field.

- UNTA_U0458-101-920-04 North Texas State Teacher’s College students pictured at the Voertman’s Teacher’s College store soda fountain, 1942.

- This photograph shows students graduating in the summer of 1935. The picture is likely taken from the roof of the power plant. The picture the students are taking will have the power plant in the background, which matches the 1935 Mural.

- Yearbook photo of Yucca Queen in 1935, Mary Willis.

- Manual Arts Building, which was built in 1914 and demolished in 1974.

- The 2017 mural installation.

- A student works to restore the mural in 2017.

- Image of the mural in the March 1936 Avesta, a campus literary journal.

[i] Richard H. Pells and Christina D. Romer, “Great Depression” Encyclopedia Britannica, Last Updated: June 28, 2017. https://www.britannica.com/event/Great-Depression

[ii] “Are You Agin It?,” The Campus Chat (Denton, Tex.), Vol. 19, No. 23, Ed. 1 Thursday, March 28, 1935, https://texashistory.unt.edu/ark:/67531/metapth306023/m1/2/?q=UNT%20students%20fight%20raise%20in%20tuition

[iii] Fishback, Price V., William C. Horrace, and Shawn Kantor. “Did New Deal Grant Programs Stimulate Local Economies? A Study of Federal Grants and Retail Sales during the Great Depression.” The Journal of Economic History 65, no. 1 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005): 36. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3875042.

[iv] “Public Works Administration” Encyclopedia Britannica. Last Updated: July 22, 2016. https://www.britannica.com/topic/Public-Works-Administration

[v] Perry Hamilton, “Public Works Administration Buildings on Campus,” 125 Year Archival Retrospective. (Denton: University Library Special Collections, August 17, 2015) http://blogs.library.unt.edu/unt125/2015/08/17/public-works-administration-buildings-on-campus/

[vi] Ibid.

[vii] Ibid.

[viii] The Yucca Yearbook of North Texas State Teacher’s College, 1935, Denton, Texas: 19, University of North Texas Libraries, The Portal to Texas History, UNT Libraries Special Collections. (texashistory.unt.edu/ark:/67531/metapth61005/: accessed June 29, 2017),

[ix] “Art Students Complete Mural.” The Campus Chat (Denton, Tex.), Vol. 20, No. 34, Ed. 1 Thursday, June 18, 1936, University of North Texas Libraries, The Portal to Texas History, UNT Libraries Special Collections. texashistory.unt.edu/ark:/67531/metapth306109/: accessed June 29, 2017

[x] Ibid.

[xi] Ibid.

[xii] Ibid.

[xiii] Courtney Jacobs, “Early Campus Residence Halls,” 125 Year Archival Retrospective. (Denton: University Library Special collections, July 11, 2016) http://blogs.library.unt.edu/unt125/2016/07/11/early-dorms/

[xiv] Ibid.

[xv] Ibid.

[xvi] Ibid.

[xvii] Ibid.

[xviii] Charles Henderson, “Five Minutes Per Day,” The Campus Chat, Vol. 19, No. 20, (Denton: Thursday, March 7, 1935) 2, https://texashistory.unt.edu/ark:/67531/metapth306019/m1/2/

[xix] Perry Hamilton, “Native American Students at North Texas,” 125 Year Archival Retrospective. (Denton: University Library Special Collections, May 19, 2015) https://blogs.library.unt.edu/unt125/2015/05/19/native-american-students-at-north-texas/

[xx] Lisa Brown, “The Forgotten Minority”: Hispanic Life at UNT,” 125 Year Archival Retrospective. (Denton: University Library Special Collections, April 22, 2015) https://blogs.library.unt.edu/unt125/2015/04/22/the-forgotten-minority-hispanic-student-life-at-unt/

[xxi] Nita Thurman, “History of Integration: 50 Years of Change at North Texas,” The North Texan, July 2004, http://northtexan.unt.edu/archives/s04/history3.htm

[xxii] Perry Hamilton, “Lost Campus Buildings.” 125 Year Archival Retrospective. (Denton: University Library Special Collections, May 9, 2016) http://blogs.library.unt.edu/unt125/2016/05/09/lost-campus-buildings/

[xxiii] Ibid.

[xxiv] “A Brief History: 1925-1952 The Beginning” College of Information: Department of Information Science, Accessed July 5, 2017, https://informationscience.unt.edu/brief-history

[xxv] James L. Rogers. The Story of North Texas: From Texas Normal College, 1890, to the University of North Texas System, 2001. (Denton: University of North Texas Press, 2002), 214.

[xxvi] Ibid., 247.

[xxvii] Ibid., 248.

[xxviii] Ibid. 219.

[xxix] Courtney Jacobs. “Early Social Clubs at UNT.” 125 Year Archival Retrospective. (Denton: University Library Special Collections, January 23, 2015) http://blogs.library.unt.edu/unt125/2015/01/23/early-social-clubs-at-unt/

[xxx] Ibid.

[xxxi] Ibid.

[xxxii] Emily Aparicio. “Voertman’s Book Store: A Fry Street Landmark.” 125 Year Archival Retrospective. (Denton: University Library Special Collections, February 7, 2016) http://blogs.library.unt.edu/unt125/2016/02/07/voertmans/

[xxxiii] Ibid.

[xxxiv] Ibid.

[xxxv] “The Corridor of Years” The North Texan, May 6, 2013, https://northtexan.unt.edu/historical-signs

[xxxvi] “Commencement Program for North Texas State Teachers College,” May 29, 1935, Denton, Texas. University of North Texas Libraries, Digital Library, UNT Libraries Special Collections, Accessed July 5, 2017, digital.library.unt.edu/ark:/67531/metadc174793/

[xxxvii] Photograph of Graduating Students, 1935, University of North Texas Libraries, Digital Library, UNT Libraries Special Collections, Accessed July 5, 2017, https://exhibits.library.unt.edu/untfirst50years/graduating-students-summer-1935

[xxxviii] UNT Yearbooks Collection. University of North Texas Libraries, Digital Library, UNT Libraries Special Collections. https://texashistory.unt.edu/explore/collections/UNTY/

[xxxix] “Yucca Favorites Are Presented at All-College Dance Saturday,” The Campus Chat, Vol. 19, No. [22], (Denton: Thursday, March 21, 1935) 3, University of North Texas Libraries, UNT Libraries Special Collections, https://texashistory.unt.edu/ark:/67531/metapth306021/m1/3/?q=1935%20%22Yucca%20Queen%22%20Deans’%20Dance

[xl] Grant Wood, “Revolt Against the City,” Art in Theory 1900-2000: An Anthology of Changing Ideas, ed. Charles Harrison and Paul Wood, (Malden: Blackwell Publishing, 2003) 435

[xli] Ibid., 436

[xlii] Ibid.

[xliii] Jerry Adler, “1934: The Art of the New Deal,” Smithsonian Magazine, June 2009, http://www.smithsonianmag.com/arts-culture/1934-the-art-of-the-new-deal-132242698/

[xliv] Perry Hamilton, “Public Works Administration Buildings,” 125 Year Archival Retrospective.

[xlv] Grant Wood, “Revolt Against the City,” Art in Theory 1900-2000, 435

[xlvi] Mary K. Coffey, “The Mexican Problem: Nation and Native in Mexican Muralism and Cultural Discourse,” The Social and The Real: Political Art of the 1930s in the Western Hemisphere, ed. Alejandro Anreus, Diana L. Linden, and Jonathan Weinberg, (University Park, PA: The Pennsylvania State University Press, 2004), 43-45

[xlvii] Alejandro Anreus, Diana L. Linden, and Jonathan Weinberg, “Introduction,” The Social and The Real: Political Art of the 1930s in the Western Hemisphere, ed. Alejandro Anreus, Diana L. Linden, and Jonathan Weinberg, (University Park, PA: The Pennsylvania State University Press, 2004), XIV

[xlviii] Leticia Alvarez, “The Influence of the Mexican Muralists in the United States: From the New Deal to the Abstract Expressionism,” (Master’s thesis, Virginia Polytechnic Institue and State University, 2001), 24, https://theses.lib.vt.edu/theses/available/etd-05092001-130514/unrestricted/thesis.pdf

[xlix] “Art Club Sponsors Murals of Mexican,” The Campus Chat, Vol. 18, No. 20, Ed. 1 (Denton: North Texas State Teachers College, Thursday, March 8, 1934), University of North Texas Libraries, Digital Library, UNT Libraries Special Collections, 1, https://texashistory.unt.edu/ark:/67531/metapth325611/m1/1/

[l] Ibid.

[li] Alvarez, “The Influence of the Mexican Muralists,” 19

[lii] Ibid.

Leave a Reply