Local Archives, Global History: Post 3 by Robbie Segars

By the early 1960s, the Country Music Association decided to shed its negative “hillbilly” image and market country music to a sophisticated blue-collared audience (Pecknold 2007, 135). This initiative caused a cultural shift in the genre aimed at promoting a clean-cut image. By the early 1970s, however, a subculture emerged that opposed this polished and commercialized Nashville sound (Cobb 1982, 87). This style of country music went by the prefix “outlaw” in reference to song themes based on criminal activities such as lying, stealing, cheating, and substance abuse. Among the leaders to spearhead this movement were songwriters Waylon Jennings, Johnny Cash, Jerry Jeff Walker, and Willie Nelson, to name just a few. During this era, Willie Nelson’s image underwent a drastic change starting with the release of his first “outlaw” album, Shotgun Willie (1973). As his fame skyrocketed, Nelson became known for his outlaw compilation albums and annual music festivals, including the ongoing summer concert, Willie’s Fourth of July Picnic. During these years, Willie Nelson hired Steve Brooks as his primary artist for promotional works. The Steve Brooks collection housed at the UNT Special Collections archives provides a glimpse into an extraordinary historical moment in country music. This collection offers a unique perspective on how one outlaw country artist both drew from and resisted country music tropes.

The basis for my archival project was to explore the artwork done by UNT alum Steve Brooks. This collection contains a broad assortment of art ranging from sketches, handbills, posters, t-shirts, and a few miscellaneous items like plastic cups, matchbooks, and an odd-looking cardboard shoe. While I consulted a diverse selection from Brook’s other clients, I focused specifically on his Willie Nelson art. I wondered what these archives could tell us about the state of country music at the specific historical moment in which Brooks worked. Who was the intended audience? By trying to understand the purpose of these artifacts, I hoped to glean a few possible motivations that guided their creation. Over the last several weeks, I searched through the Steve Brooks collection to see whether I could detect reoccurring themes with the hope that I might start a conversation about their historical relevance.

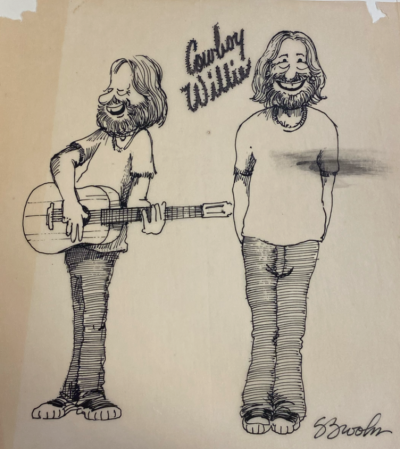

The first box I opened from the archives contained approximately fifty manila folders, roughly 12 x 10 inches in size, with sketches that ranged from the early 1970s to the early 1980s. Based on the drawings from this box, which were consistent throughout this collection, Brooks could best be classified as a cartoonist with a few pieces that resembled realistic portraits. The first folder had a Willie Nelson caricature holding his famous nylon-stringed guitar wearing a t-shirt, jeans, and tennis shoes, as seen in figure 1.

Figure 1. Steve Brooks Collection, Box 5, Folder 1, “Cowboy Willie,” Sketch, undated.

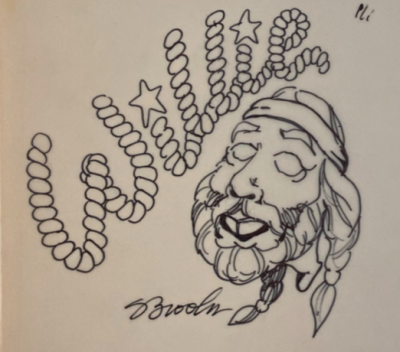

He sported a thick bushy beard, long shaggy hair, beady eyes, and a wide, friendly grin. Next to his name read “Cowboy Willie” in a cursive font designed to look like a cactus. A few folders later, another Nelson cartoon appeared (figure 2) with a similarly bearded smile, but with the addition of a headband holding back his braided hair.

Figure 2. Steve Brooks Collection, Box 5, Folder 4, “Rope Letter, Willie with Character,” undated.

The “Willie” logo in this picture was written with a lasso and presumably two Texas stars to dot the lowercase I’s. The first themes I noticed appeared to be based on wild west cowboy tropes such as lassos, cactuses, cow skulls, and boot spurs.

While these associations with country music were somewhat common, there were apparent differences that clashed with previous generations’ straight-laced style worn by Buck Owens, Hank Williams, Bob Wills, and even Willie Nelson himself.

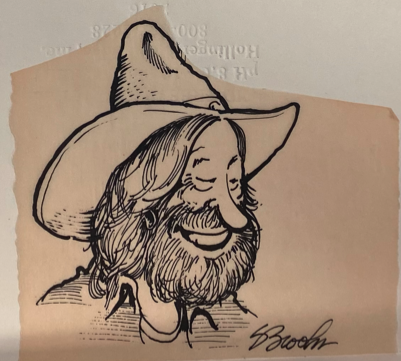

Figure 3. Steve Brooks Collection, Box 5, Folder 37, “Willie for ’75,” 1975.

By the 1970s, Nelson’s identity had more in common with the hippie counterculture of the 1960s. The outlaw country version that Brooks captured in his caricatures emphasized Nelson’s rejection of clean-cut country values (figure 3). His long braided, scruffy beard, worn-out t-shirts, jeans, and tennis shoes contrasted starkly with the crewcut, freshly shaven, collared-shirt cowboy image he had formerly sported. His carefree facial expressions were another feature that struck me as thematic. Indeed, early country music stars almost always smiled. It occurred to me that Willie Nelson’s smile in the Brooks caricatures might be drug-induced (see figure 4).

Figure 4. Steve Brooks Collection, Box 7, Folder 13, “Premium Willie Music in Wichita Falls, Texas – Sketch Studies,” 9-15-1978.

By the 1970s, Nelson made his affection for drugs, especially marijuana, well known to his fans—a reputation he still carries today (Patoski, 2008). It is plausible that Brooks emphasized this side of Nelson’s personality to appeal to his outlaw country audience. Even his choice to use cartoons undercuts the sophisticated image that mainstream country aimed to instill. Aside from one or two still-life drawings—among the select few where Nelson is not smiling—cartoons dominated this collection, like in figure 5.

Figure 5. Steve Brooks Collection, Box 5, Folder 113, “Air Willie – Sketch,” 1981-1982.

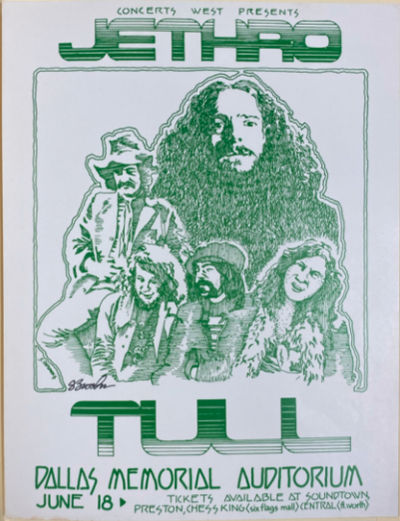

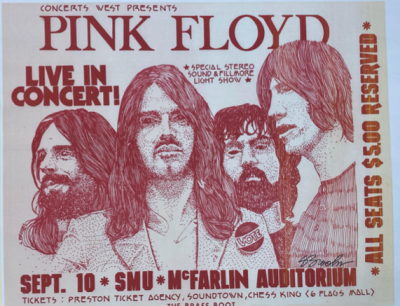

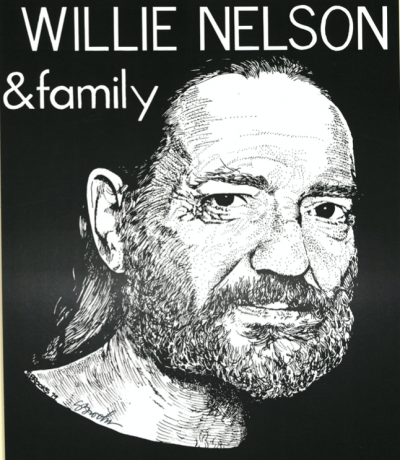

For comparison purposes, I consulted a few boxes with flyers for Brooks’ other high-profile clients including the Allman Brothers, the Beach Boys, Elton John, Alice Cooper, Jethro Tull, Pink Floyd, and the Eagles. From these samples, I was surprised that none of them had cartoon depictions of the musicians. Some had only band logos with a photograph, while others contained a few life-like drawings similar to those from the Willie Nelson collection (figures 6-8).

Figure 6. Steve Brooks Collection, Box 2, Folder 41, “Jethro Tull – Dallas Memorial Arboretum,” 6-18-1972.

Figure 7. Steve Brooks Collection, Box 2, Folder 46, “Pink Floyd – SMU McFarlin Auditorium,” 9-10-1972.

Figure 8. Steve Brooks Collection, Box 5, Folder 12, “Willie Nelson and Family Sportatorium,” 1-15-1980

The date on the outside of the folders showed that these pieces originated from 1972 to 1975, the same time period when Brooks worked with Willie Nelson. This detail reaffirmed my suspicion that the Willie Nelson art expressed cultural values and ideologies meant for a specific audience.

After learning about country music’s history in conjunction with events from Willie Nelson’s life, I began to see Brooks’ art in a new light. My goal was never to discover a missing piece of popular music history; rather, I wanted to provide some insight into how country music’s cultural values started to change in the 1970s. More importantly, I wanted to learn how Steve Brooks reflected these changes with art that would still resonate with Willie Nelson fans as they gather for his annual Fourth of July Picnic each year. While working with the Steve Brooks archives, I was unable to glean how much artistic freedom he had for these commissions. However, the sheer size of this collection convinced me that his clients must have felt he had an innate gift for accurately capturing their musical identity with his drawings.

Bibliography

Cobb, James C. 1982. “From Muskogee to Luckenbach: Country Music and the ‘Southernization’ of America.” Journal of Popular Culture (16-3): 81-91.

Nelson, Willie. 2015. It’s a Long Story: My Life. New York City: Little, Brown, and Company.

Patoski, Joe Nick. 2008. Willie Nelson: An Epic Life. New York City: Little, Brown, and Company.

Pecknold, Diane. 2007. “Masses to Classes: The Country Music Association and the Development of Country Format Radio, 1958-1972.” in The Selling Sound: The Rise of the Country Music Industry, 133-167. Durham: Duke University Press.

Bill Sanderson

Interesting take on Steve Brooks’ prodigious work. He is/was an Oak Cliff artist and evolved with the early

Dallas counter culture; himself a hipster artist and music aficionado, he found Willie early on, and lucky for us, set about to portray and shape the myth. I figure he was part of it as he illustrated it. Good man, fine artist.