World AIDS Day has been celebrated on the first day of December every year since its founding at the height of the AIDS epidemic in 1988. It provides an annual opportunity to show support for those living with AIDS and to remember those we have lost; to look back at how it started and see how far we have come; and to realize that the fight against AIDS is not yet over.

In the earliest days of AIDS, when the disease was less understood and the government was dragging its heels in formulating any kind of effective response to the growing epidemic, Surgeon General C. Everett Koop proved an unlikely but effective ally in changing public policy. In 1981, the very conservative Dr. Koop was nominated by President Reagan to be Surgeon General and was sworn into office in January 1982 after a contentious confirmation process. Opponents on the left feared that his appointment was giving political ideology priority over public health, but as Michael Specter put it in his 2013 Postscript for The New Yorker, “Koop turned out to be a scientist who believed in data at least as deeply as he believed in God. And he proceeded to alienate nearly every supporter he had on the religious and political right.”

As AIDS first began to spread, there was a great deal of uncertainty over just how contagious the disease was and how it was being transmitted. AIDS seemed to resemble earlier catastrophes such as bubonic plague and yellow fever. Some proposed drastic measures, such as mass quarantines and mandatory screening of at-risk populations. Many people treated AIDS patients with disdain. The disease had become associated with populations outside the mainstream: gay men, drug addicts, and the sexually promiscuous. At times, this social attitude even took on a religious tone; victims were accused of being under a curse for their immoral behavior.

Dr. Koop recognized early on that the disease that came to be known as AIDS had the making of an epidemic, but differentiated this disease from easily transmitted contagions such as bubonic plague, yellow fever, Spanish flu, and the more recent COVID-19. Those diseases required extraordinary public health measures such as mandatory testing and quarantine of infected patients. AIDS, in contrast, was a chronic disease that could be managed with drugs and behavioral changes and could be prevented by educating the public in how to protect themselves without discriminating against AIDS sufferers in schools, the workplace, and housing.

The conservative Reagan administration, squeamish about starting a public debate over homosexuality, sex education, and drug abuse, contributed a small amount of funding for medical research, but largely ignored the disease and its victims. For two years Assistant Secretary of Health Edward Brandt—Koop’s immediate superior—excluded Koop from the Executive Task Force on AIDS and forbade reporters to ask the Surgeon General questions about AIDS. Koop raised the objection that “you can’t talk of snake poisoning without mentioning snakes.”

In 1985 the death from AIDS of actor and celebrity Rock Hudson, a personal friend of Ronald and Nancy Reagan, served to focus attention of the public and the White House on the seriousness of the disease. During the same year, a test was developed to identify AIDS antibodies in the blood supply used for transfusions.

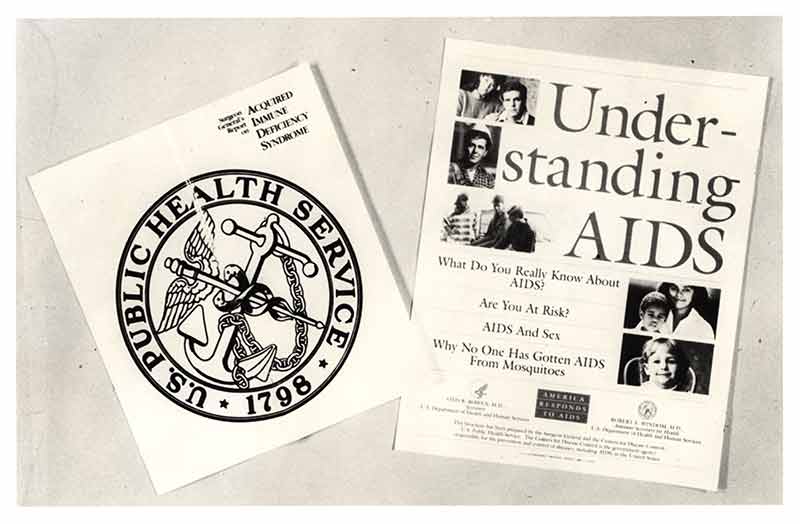

In February 1986, President Reagan finally authorized Koop to produce a Surgeon General’s Report on Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome. There was never any direct, formal request. During a speech given to employees of the Department of Health and Human services on February 5, 1986, Reagan mentioned casually that “I’m asking the Surgeon General to prepare a major report to the American people on AIDS.” Fortunately, Surgeon General Koop happened to be at the meeting and took the hint! With the assistance of a few trusted advisors, Koop wrote the report himself, at a stand-up desk in the basement of his home, rather than delegating the writing as government officials so often do. The finished report was presented before the President and the cabinet before going public. To avoid excessive, nitpicky meddling, he had the pamphlet printed on very expensive paper. On October 22, 1986, he released the finished report at a press conference.

The Surgeon General’s Report discussed symptoms of AIDS and explained frankly how it was spread—through sexual intercourse, sharing of contaminated needles among drug users, from infected mother to child during pregnancy or birth, and through transfusion of contaminated blood or blood products. Readers were assured that AIDS could not be transmitted through casual contact. The report advised prevention through a program of compulsory sex education in schools, increased use of condoms, and voluntary, confidential testing. AIDS was a chronic, incurable disease, but it could be managed with drugs.

Though the Surgeon General’s Report was not received without controversy (objections were raised to the mention of sex education and condoms; Koop was burned in effigy), it was notable for treating AIDS as a health issue rather than a moral issue and for giving the victims of the disease hope that they could extend their lives, participate fully in society, and be treated with respect and compassion.

In 1988, misinformation was still being spread about how AIDS is transmitted. Millions of Americans still believed they could get AIDS from cats, from mosquito bites, from toilet seats, from donating blood, even from sitting next to a child in school. Another misunderstanding being spread was that only people from certain “high risk groups” were infected with AIDS. In order to counter this constant stream of misinformation, the Surgeon General sent out a mailer entitled Understanding AIDS to everyone on the IRS mailing list. It was the largest mailing in American history: 107,000,000 copies. The brochure explained in plain language exactly how one can and can’t get AIDS.

At the time of Surgeon General Koop’s report, a person diagnosed with AIDS had little chance of surviving the next two or three years, and next to no chance of surviving longer than that. Today there is still no cure, but with modern treatments AIDS patients are living long and fulfilling lives. Still, it is important to remember on World AIDS Day and after that there is a constant need for us all to unite in the fight to to eliminate the disparities and inequities that create barriers to HIV testing, prevention, and access to HIV care.

For more information about what you can do to make a difference, see hiv.gov.

Article by Bobby Griffith.

Bibliography

“AIDS, the Surgeon General, and the Politics of Public Health.” The C. Everett Koop Papers. National Library of Medicine: Profiles in Science.

“The AIDS Epidemic.” Reports of the Surgeon General. National Library of Medicine: Profiles in Science.

Koop, C. Everett. “The Early Days of AIDS, as I Remember Them.” Annals of the Forum for Collaborative HIV Research 13, no. 2 (2011).

Koop, C. Everett Understanding Aids. Rockville MD: U.S. Dept. of Health and Human Services, 1988.

Specter, Michael. “Postscript: C. Everett Koop, 1916–2013.” The New Yorker. February 26, 2013.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Surgeon General’s Report on Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Dept. of Health and Human Services, 1986.

Leave a Reply