Carol L. Highsmith, photographer. [Second Floor, East Corridor. Mural depicting Lyric Poetry (Lyrica) in the Literature series by George R. Barse, Jr.. Library of Congress Thomas Jefferson Building, Washington, D.C.]. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division.

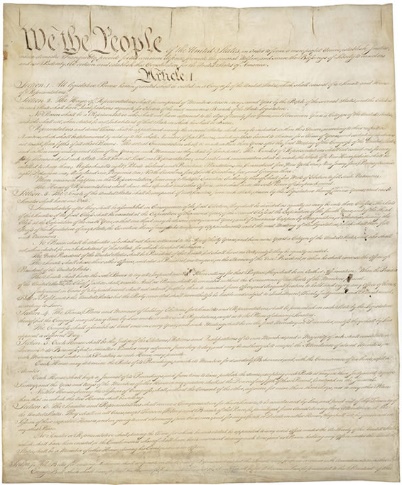

April is National Poetry Month, and the perfect time to shine a spotlight on a hidden treasure in the Government Documents collection at Sycamore Library. You might be surprised to learn how much poetry, writings about poetry, and even performances of poetry are available in the often seemingly dry-as-a-desert world of government information, and what a significant role our government plays in preserving and promoting the rich tapestry of our poetic heritage. From studies of classic authors to lessons in how to write poetry, government documents contain a plethora of poetic resources.

Poetry as Literature

Perhaps the richest source of poetic resources in government is the Library of Congress. Their website hosts a treasure trove of poetry-related materials, including finding aids to help you.

Finding Poems: Is there a poem you half-remember—maybe you can quote a line or phrase, or you think you know the author, but can’t remember the title? This is a list of tools and resources from the Library of Congress that can help you identify that elusive poem using whatever information you might have. And remember, if none of these suggestions proves helpful, you can always Ask Us.

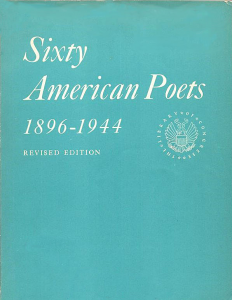

Sixty American Poets, 1896-1944: In 1945, while he was a poet in residence at the Library of Congress, Allen Tate compiled this bibliography of sixty of the most important American poets of the previous 50 years (not leaving himself out), listing the chief works, recordings of works, and major criticism or biographies of each poet, and providing his own highly opinionated commentary on each. A decade later, Kenton Kilmer of the Legislative Reference Service revised and expanded the content with more recently published material while adhering to Tate’s original list of sixty poets.

Poet Laureate

From 1937 to 1986, the Library of Congress had a position called Consultant in Poetry to the Library of Congress (sometimes abbreviated as Consultant). Their job was similar to that of a reference librarian, and the consultant’s job duties consisted primarily of serving as a collection specialist and a resident scholar in poetry and literature.

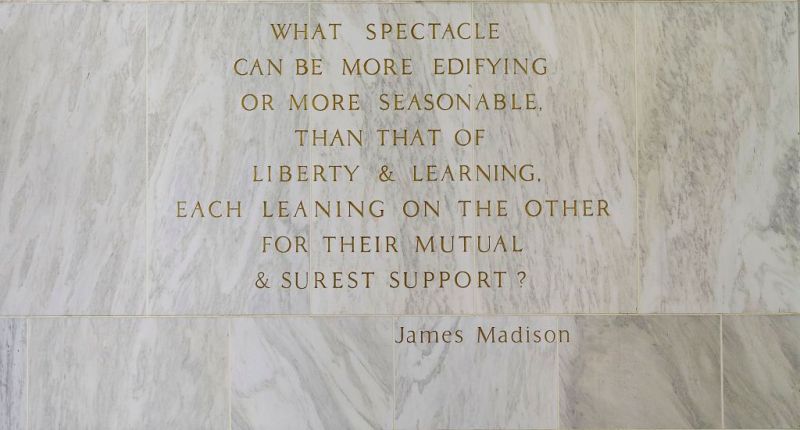

On December 20, 1985, an Act of Congress (Public Law 99-194) established the position of Poet Laureate Consultant in Poetry (usually abbreviated as Poet Laureate). This position has focused more on more on organizing local poetry readings, lectures, conferences, and outreach programs. Nearly half of the laureates have taken on a signature Poet Laureate Project to improve the national appreciation of poetry.

The Library of Congress webpage has a list of all Consultants and Poets Laureate with a short biography of each.

Ada Limón is the current Poet Laureate. She was appointed by Librarian of Congress Carla Hayden on July 12, 2022 and reappointed for a historic two-year second term on April 24, 2023.

Gertrude Clarke Whittall Poetry and Literature Fund

This fund was established by philanthropist Gertrude Clarke Whittall in 1950 to promote the appreciation of poetry, drama, and other literature. On April 23, 1951—the anniversary of William Shakespeare’s birth—a Poetry Room was dedicated where the library hosts lectures, poetry readings, and other literary events supported by this fund. These are some of the many chapbooks that were published by the Library of Congress as a permanent record of the lectures given by illustrious poets and scholars with the support of the Gertrude Clarke Whittall Poetry and Literature Fund.

Anniversary Lectures, 1959: These lectures include “Robert Burns, 1759,” by Robert Hillyer; “Edgar Allan Poe, 1809,” by Richard Wilbur; and Alfred Edward Housman, 1859 ,” by Cleanth Brooks.

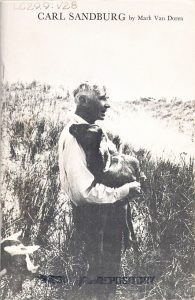

Carl Sandburg: With a Bibliography of Sandburg Materials in the Collections of the Library of Congress is a lecture on the life and works of Sandburg presented in the Library of Congress on January 8, 1968 by Mark Van Doren. It includes a poem about Sandburg—”Where a Poet’s From,” by Archibald MacLeish—and a bibliography of works by Sandburg in the Library of Congress.

Wallace Stevens: The Poetry of Earth is a lecture by A. Walton Litz that locates the essence of the poetry of Wallace Stevens in a constant struggle to depict the inner, personal world of pure imagination while remaining faithful to the external world of objective facts.

Walt Whitman: Man, Poet, Philosopher: These three lectures were delivered at the Library of Congress by Gay Wilson Allen, Mark Van Doren, and David Daiches on January 10, 17, and 25, 1955, to celebrate the 100th anniversary of the first edition of Whitman’s poetry collection Leaves of Grass.

State University Publications

State universities are government institutions and frequently publish poetry either in the form of books issued by their university presses, or through a literary journal that publishes poems by students or by professional poets.

100 Love Sonnets / Cien sonetos de amor is a classic collection of poems by Pablo Neruda translated by Stephen Tapscott and published in a beautifully designed volume by University of North Texas Press with the original Spanish poems and the English translations appearing side by side on facing pages.

The Green Fuse, named after a Dylan Thomas poem, was a literary journal published by North Texas State University from 1971 to 1990 (in 1988 the NTSU was renamed the University of North Texas). This annual print publication showcased art, poetry, and prose created by NTSU/UNT students. In 1977, according to a letter by alumnus Douglas Ray published in The North Texan, the journal was almost not published because of a lack of funds, but enough funds were raised privately to publish a limited edition entitled Shadow of the Green Fuse. The following year a major effort was made to secure funding from the Student Service Fund, and in the spring of 1978 publication of The Green Fuse was renewed. In 1990 the journal was continued under the new title North Texas Review.

The Texas Review is a literary review showcasing fiction, poetry, creative nonfiction, short plays, and comics/art. The Texas Review partners with Texas Review Press (the University Press of Sam Houston State University) and Sam Houston State University’s MFA in Creative Writing, Editing, and Publishing to publish two issues per year.

Poetry as History

Ever since ancient times, poetry has been used as a popular medium for vividly conveying personal experiences of wars, social upheavals, and other major historical events.

The Battle Line of Democracy: Prose and Poetry of the World War is an anthology of patriotic poetry and prose compiled during World War I for the edification and inspiration of American children and published by the U.S. Committee on Public Information. The Committee on Public Information was the first large-scale propaganda agency of the U.S. federal government, established in 1917 to raise public support for the war effort.

Poetry in Response to 9/11: A Resource Guide: The terrorist attack on the United States that took place on September 11, 2001 was an overwhelming experience that elicited a number of varied responses. Many of these responses were took the form of poetry, which can express the deepest, most intense emotions. The Library of Congress has compiled a guide to these poems that includes an anthology of selected poems written or published within a year of the attacks; links to online collections of poems archived by various institutions; a bibliography of print publications about the September 11 attacks; and some suggestions for where to find additional poems.

Operation Homecoming: Writing the Wartime Experience is an anthology resulting from a series of writing workshops sponsored by the National Endowment for the Arts for returning troops and their families at military installations in the United States and overseas. Taught by professional novelists, poets, historians, and journalists, some of whom were veterans themselves, these workshops provided service men and women with the opportunity to write about their wartime experiences in Afghanistan and Iraq using a variety of literary forms, including fiction, poetry, letters, essays, memoirs, and personal journals. Other formats in which these works are available include Operation Homecoming: Writing the Wartime Experience [E-Book] and Operation Homecoming: Writing the Wartime Experience [Audio CD], which includes performances of creative works that memorialize experiences of Americans in the Civil War, the two world wars, and the Vietnam conflict.

“A Critique of Coronavirus” is a poem by Elana R. Osen, a specialty registrar at St. George’s University Hospital in London, that was published the July 2020 issue of Emerging Infectious Diseases, a journal of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). It describes the peculiar experience of “looking around and not seeing or sensing anything observably different from normal, whilst at the same time being in the midst of a pandemic.” You can listen to a podcast of Dr. Osen discussing with Sarah Gregory her experience of writing the poem, or read a transcript of the podcast.

“Of Those We Have Lost and Those Who Have Saved So Many Others” by Terence Chorba is an article published later during the pandemic, in the July 2022 issue of Emerging Infectious Diseases. It looks at the modernist calligrams of Guillaume Apollinaire, a Belarus-born French poet who was one of the many casualties of the great influenza A (H1N1) pandemic of 1918, and also comments briefly on two other poets who lost their lives during the First World War, not from battle wounds, but from infectious diseases: John McRae, author of “In Flander’s Fields,” who died of meningitis, and Rupert Brooke, author of many well-known war poems, who died from an infected mosquito bite. Comparisons and contrasts are drawn between the 1918 flu pandemic and the Covid-19 pandemic.

Poetry and Special Populations

These documents are just a few samples of the ways government agencies have helped marginalized populations—often populations marginalized by the government—use poetry as a tool for self-expression, self-awareness, and a way to explore and embrace their own unique life experiences.

First Peoples

When it was established in 1962, the Institute of American Indian Arts was a high school funded by the Bureau of Indian Affairs. Today they are a world-class institution that offers certificate, undergraduate, and low-residency graduate programs as well as lifelong learning classes, all taught from indigenous perspectives. Joy Harjo, the 23rd Poet Laureate Consultant in Poetry to the Library of Congress, attended IAIA in the 1960s when it was still a high school. From the beginning they have encouraged students to experiment, and over the years the IAIA has curated a large collection of student works. Poems written by students who attended IAIA from 1962 to 1965 are collected in a 27-page chapbook with the lengthy title Anthology of Poetry and Verse: Written by Students in Creative Writing Classes and Clubs during the First Three Years of Operation (1962-1965) of the Institute of American Indian Arts, Santa Fe, New Mexico.

Incarcerated Persons

The Echo is a monthly newspaper produced by and for inmates in the Texas criminal justice system. In addition to news stories, policy updates, opinion pieces, recipes, and other information, each issue features original works such as poetry and fiction that serve as an outlet for the inmates’ creative expression. Like most publishers of poetry, The Echo always has far more submissions than space to print them all (the editors claim to have over 100 submissions approved for publication at any given time), but inmates are always encouraged to send in their work.

For a study of the purpose and effectiveness of this publication, see A Critical Examination of “The Echo”: Prison Publication of the Texas Department of Corrections, a 1977 thesis by NTSU Journalism student David A. Hadeler.

The Elderly

Care and Independent Living Services for Aging: Competency Based Teaching Module is the rather prosaic title of a textbook published in 1977 by the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare (HEW) to train future workers in the field of occupational home economics. This particular module includes an anthology of poems and prose excerpts about love and old age, general attitudes toward aging, religious perspectives on aging, and death and dying that can be used to stimulate discussions among students about how different people experience the aging process.

Poetry in the Classroom and the Community

Educational institutions and libraries across the country receive funding and support from government grants to promote literacy and poetry appreciation. These initiatives often include poetry workshops, readings, and community outreach programs aimed at fostering a love of language and literature among people of all ages and backgrounds.

Found Poetry is created by selecting words, phrases, lines, and sentences from one or more written documents and combining them into a poem. Raw material for found poems can be selected from newspaper articles, speeches, diaries, advertisements, letters, food menus, brochures, short stories, manuscripts of plays, shopping lists, and even other poems. A collection of text resources written by well-known authors is provided in this online set of primary sources from the Library of Congress.

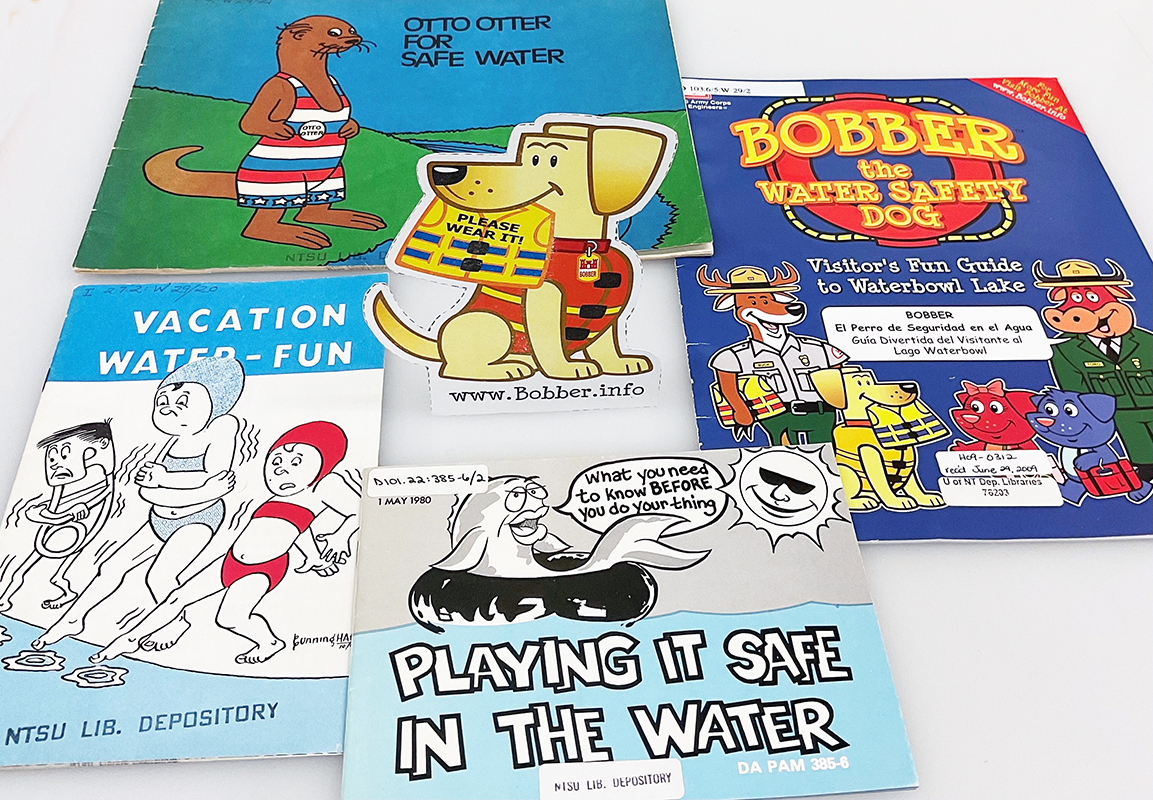

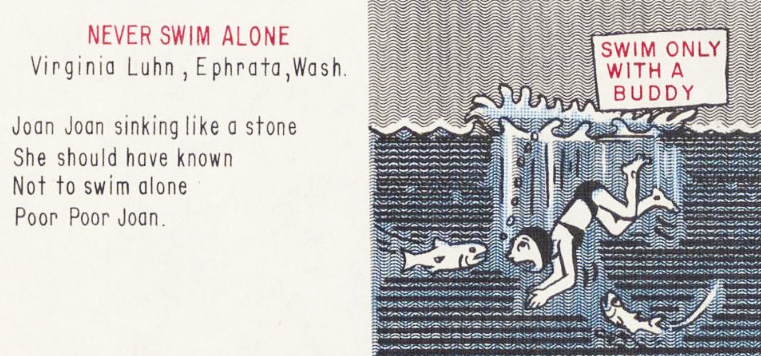

Vacation Water-Fun is an anthology of poems written by schoolchildren to remind themselves of important concepts regarding water safety. The poems were written as part of an education initiative by the Bureau of Reclamation and the anthology provides an enduring record of their experience. The children’s poems are illustrated with whimsical cartoons by Bureau of Reclamation employee David Cunningham.

ERIC (Education Resources Information Center) is a comprehensive, easy-to-use, searchable, Internet-based bibliographic and full-text database of education research and information. ERIC indexes education research found in journal articles, books, and gray literature. (Gray literature includes materials produced by nonprofits, advocacy organizations, government agencies, and other sources not typically made available by commercial publishers.) Depending on the copyright status, materials indexed in the ERIC database may be available as full text or as a citation to an external source.

The ERIC database contains many useful articles and books on using poetry in the classroom, either teaching about poetry itself, or using poetry to enhance the teaching of other subjects. These are just a few examples of the intriguing and innovative content you can find here:

“#Poetryisnotdead: Understanding Instagram Poetry within a Transliteracies Framework” is an article by Kate Kovalak and Jen Scott Curwood published in Literacy, the official journal of the United Kingdom Literary Association. It is not a government publication, but the full text of this article is available for free through ERIC. This fascinating case study examines the very recent phenomenon of adolescents creating multimodal creative works such as digital poetry enhanced by photo-editing apps, then sharing their creations with an online audience. The authors conclude that the interaction of creators of instapoetry and their audience has led to an increased exposure and relevance of poetry writing and appreciation; a space for student-centered writing, reading, and analysis of poems; and a relevant method of peer review and collaboration.

“Green Writing: The Influence of Natural Spaces on Primary Students’ Poetic Writing in the UK and Australia” is an article published by Paul Gardner and Sonia Kuzich in the Cambridge Journal of Education. This study contrasts the experiences of students writing about nature from within the classroom, using a vicarious experience of nature as a stimulus, versus students who write their poems based on a direct experience of nature. The results suggest that standards of writing improve when students are given direct contact with natural spaces.

Teaching Poetry Writing to Adolescents, a book by Joseph Tsujimato published by the ERIC Clearinghouse on Reading and Communication Skills, contains many exercises that teachers can use in their classrooms to teach students how to write poetry. These exercises can also be used to teach yourself how to write poems!

Some of the most interesting teaching materials in ERIC are those that describe how to use poetry to enhance the teaching of decidedly non-poetic subjects.

“Poetic License: Using Documentary Poetry to Teach International Law Students Paraphrase Skills” is an article by Robin Nilon published in InSight: A Journal of Scholarly Teaching that demonstrates how studying the poems of poet-lawyer Charles Reznikoff can help law students learn the art of paraphrasing legal cases. Student first summarize Reznikoff’s own poems inspired by reported legal cases into prose form, then they try their hand at summarizing other reported cases as poetry. Students improved their paraphrase skills as well as their understanding of policy analysis. This teaching technique can also be applied to improve students’ critical thinking and writing skills in the humanities, sciences, and social sciences. (The device of transforming prose into poetry and poetry into prose is not new—Benjamin Franklin describes in his autobiography how he expanded his vocabulary and improved his writing skills by translating articles from the Spectator into verse, then back to prose.)

“Writing and Reading Multiplicity in the Uni-Verse: Engagements with Mathematics through Poetry” is an article by Nenad Radakovic, Nenad, Susan Jagger, and Limin Jao published in For the Learning of Mathematics: An International Journal of Mathematics Education. Their article describes the types of mathematical poetry, provides examples of several poems by mathematician-poets, relates their variable results at conducting an in-service teacher education workshop in mathematical poetry, and suggests how the concrete imagery and emotional content of poems can provide students with a non-threatening and holistic way to engage with “a field of study that is often seen as disembodied and abstract.”

Poetry as Therapy

The National Association for Poetry Therapy provides this useful definition of poetry therapy:

Poetry therapy is the use of language, symbol, and story in therapeutic, educational, growth, and community-building capacities. It relies upon the use of poems, stories, song lyrics, imagery, and metaphor to facilitate personal growth, healing, and greater self-awareness. Bibliotherapy, narrative, journal writing, metaphor, storytelling, and ritual are all within the realm of poetry therapy.

Government agencies focused on health and wellness have found reading or writing poetry to be an effective way to help patients heal from traumatic experiences as well as an effective everyday practice that anyone can use to improve their own self-awareness and general well-being.

In the 1990s the Texas Department of Health, in cooperation with several other agencies, encouraged therapists to use poetry writing as well as the creation of visual art to help victims of sexual abuse share their often long-suppressed stories and give voice to their overwhelming and often difficult to express feelings. A selection of poems and artworks were published in two anthologies named after each year’s theme for Sexual Assault Awareness Month—Sharing the Secret, Surviving the Silence from 1993 and Listen to the Children from 1995.

Poetry in Performance

Long before it was a written art form, poetry was primarily oral. Sung, chanted, or recited, oral poetry has been sometimes improvised on the spot, sometimes passed down from generation to generation and developed communally. (See D.M. Kgobe’s essay “ORAL POETRY: The Poet’s Performance and His Audience in an African Context with Special Reference to the Northern Sotho Society” for a discussion of how these techniques and traditions have continued into current times.)

Several government publications and websites contain recorded performances of poetry, often by the poets themselves. Other documents provide advice on creating oral poetry and sharing it with the local community.

Inaugural Poems

Inaugural Poems in History: Only four United States presidents so far have invited poets to read a new poem, specially composed for the occasion, at their inaugurations. This page at the poets.org website includes the text of each poem and a link to a video of the poet reading at the inauguration. (Robert Frost was having trouble seeing his manuscript because of the sun’s glare bouncing off the snow, so he ended up reciting his poem “The Gift Outright” from memory instead of reading the newly composed poem, but you can read both poems here.)

You can also watch several of the poets reading their inaugural poems on YouTube:

These are several posts from the Library of Congress From the Catbird Seat blog that discuss inaugural poets and their poems:

Amanda Gorman recites her inaugural poem, “The Hill We Climb,” during the 59th Presidential Inauguration ceremony in Washington, Jan. 20, 2021. President Joe Biden and Vice President Kamala Harris took the oath of office on the West Front of the U.S. Capitol. (DOD Photo by Navy Petty Officer 1st Class Carlos M. Vazquez II) CC BY 2.0

Library of Congress

The Archive of Recorded Poetry and Literature is an extensive archive of live recordings of poets and other writers participating in public literary events at the Library of Congress in Washington, DC, plus studio recordings made in the Library’s Recording Library. Hear renowned poets such as Robert Frost, Audre Lorde, Derek Walcott, Denise Levertov, Robert Penn Warren, Maya Angelou, and many others reading and discussing poetry by themselves and their colleagues.

From the Catbird Seat is the official poetry and literature podcast of the Library of Congress. Their archive features recordings of poets reading and discussing their work at the Library of Congress, and offers behind-the-scenes interviews with special guests. In 2023, From the Catbird Seat was replaced by the Bookmarked blog, which combines From the Catbird Seat with the National Book Festival blog.

White House

James Earl Jones Performs Shakespeare at the White House Poetry Jam: On May 12, 2009, in the first year of his presidency, Barack Obama initiated the White House Poetry Jam, more formally known as the White House Evening of Music, Poetry, and the Spoken Word.

In his opening remarks, President Obama summed up the purpose of this event:

Now, we’re here tonight not just to enjoy the works of these artists, but also to highlight the importance of the arts in our life and in our Nation, in our Nation’s history. We’re here to celebrate the power of words and music to help us appreciate beauty, but also to understand pain, to inspire us to action and to spur us on when we start to lose hope, to lift us up out of our daily existence, even if it’s just for a few moments, and return us with hearts that are a little bit bigger and fuller than they were before.

The highlight of the evening was this intensely moving performance of a monologue from Shakespeare’s Othello by Academy Award winning actor James Earl Jones.

Also on the program was Lin-Manuel Miranda’s preview of a little project he was working on at the time—a hip-hop musical called Hamilton.

NASA

In Memoriam: Ray Bradbury 1920-2012: One of the more unlikely government sources of recorded poetry is NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory. In this tribute to the late science fiction author Ray Bradbury, posted on YouTube the day after his death in 2012, Bradbury reads his poem “If Only We Had Taller Been” during a symposium with Arthur C. Clarke, journalist Walter Sullivan, and scientists Carl Sagan and Bruce Murray. The symposium took place on November 12, 1971, the evening before Mariner 9 began its orbit around Mars and became the first spacecraft to orbit another planet.

ERIC (Educational Resources Information Center)

“A Poetry Coffee House: Creating a Cool Community of Writers,” by Kristen Ferguson, provides tips and ideas for teaching elementary and secondary students how to share their writing through a coffee-house style poetry reading. This activity includes a discussion about poetry, a poetry writing workshop, and an open mike sharing session. The article, provided for free through the Educational Resources Information Center (ERIC) database, originally appeared in Reading Teacher 71, no. 2 (September 2017): 209–13. doi:10.1002/trtr.1610.

A Reason to Celebrate

As we celebrate National Poetry Month, let us not overlook the invaluable contributions of federal, state, and local government agencies in preserving, promoting, and honoring the art of poetry. Through its publications, websites, and initiatives, the government provides a platform for poets to share their voices, preserves the poetic heritage of the nation, and cultivates a deeper appreciation for the power of language and expression.

So, whether you’re delving into the archives of the Library of Congress, exploring the publications of the Government Publishing Office, or participating in poetry events sponsored by federal agencies, take a moment to appreciate the rich poetic resources to be found in government documents. Happy National Poetry Month!

Do You Want to Know More?

The UNT Libraries Subject Guide Poetry in Government Publications lists more government resources related to poetry.

Visit Sycamore Library on the University of North Texas Campus to explore the many poetic resources in our Government Documents Collection. Sycamore Library is also host to the UNT Libraries Juvenile and Curriculum Materials Collections, which contain many children’s and young adult books related to poetry.

If you need assistance with finding or using government information, please visit the Service Desk in the Sycamore Library during regular hours, contact us by phone (940) 565-4745), or send a request online to govinfo@unt.edu.

If you need extensive, in-depth assistance, we recommend that you e-mail us or call the Sycamore Service Desk at (940) 565-2870 to make an appointment with a member of our staff.

Article by Bobby Griffith