This Sunday, March 8, 2020, most of the population of the United States will perform the annual chore of setting their time-keeping devices forward by one hour, as we enter the seemingly ever-lengthening portion of the year referred to as Daylight Saving Time—surely an ironic term for the many students who will lose one precious hour of their Spring Break this year! (Usage note: don’t ever call it Daylight Savings Time, even if you’re a congressman. It’s not a bank account.)

Historical Background

Benjamin Franklin is credited with first conceiving the idea for a daylight-saving law, which he proposed (perhaps as a joke) in an anonymous and humorously-worded letter to the editor published in the Journal de Paris in 1784.

Benjamin Franklin is credited with first conceiving the idea for a daylight-saving law, which he proposed (perhaps as a joke) in an anonymous and humorously-worded letter to the editor published in the Journal de Paris in 1784.

The first serious proposals for such a law came from the entomologist/astronomer George V. Hudson in New Zealand in 1895 and 1898, and from the builder William Willett in England in 1907. (Willett, incidentally, was the great-great-grandfather of Chris Martin of Coldplay, the band responsible for the songs “Clocks” and “Daylight.”)

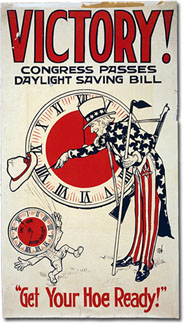

Franklin’s whimsical idea was not taken seriously in the United States until Congress passed the Standard Time Act of 1918 to economize on fuel during the First World War. By then, several European countries had already adopted some version of a daylight-saving law.

The law turned out to be quite unpopular in the U.S., especially among farmers, who found it unnatural and disruptive, and it was abolished immediately after the war. It was reinstated during the Second World War, then abolished again after that war, then reinstated inconsistently by various state and localities. It has been a continual source of controversy up to the present day.

A 2020 Congressional Research Service Report for Congress summarizes the contentious history of this law over the decades.

Observance

The most recent change to the dates of observance of Daylight Saving Time was implemented as Section 110 of the Energy Policy Act of 2005. Under current law, Daylight Saving Time (DST) is observed in the United States from 2:00 a.m. on the second Sunday in March until 2:00 a.m. on the first Sunday in November, theoretically saving energy during the longer days and keeping children safe (and candy companies in business!) during the prime trick-or-treating hours of Halloween.

A few U.S. states and territories do not observe DST:

- Arizona (except for the Navaho Nation, which does observe DST)

- Hawaii

- American Samoa

- Puerto Rico

- The Virgin Islands

Controversies

Among the advantages that have been imputed to DST are that it saves electricity and the money spent on lighting during the evening hours; it offers more daylight hours for recreation after our jobs, studies, or chores and encourages people to spend more time exercising and socializing; it stimulates tourism and business; and it reduces crime and traffic accidents during the evening hours.

Opponents to DST have objected that changing the clocks twice a year is inconvenient, unnatural, and confusing; the extra cost of air-conditioning at night negates any savings in reduced lighting; the extra driving drives fuel-spending up and generates pollution; the extra hour of darkness in the morning leads to more traffic accidents and endangers children on their way to school; and the jolt to our inner circadian clocks is unhealthy.

Many of these assertions for and against have been based more on hunches than on proven facts, but there have been several studies of the effects of daylight-saving laws in various places around the world.

A 1975 study by the U.S. Department of Transportation indicated that extending DST from a six-month period to an eight-month period might have modest benefits in the areas of energy conservation, traffic safety, and reduced violent crime, although their conclusions were not asserted with much confidence.

A 2008 report by the U.S. Department of Energy indicated a small savings in electricity during the daylight saving period, while a study of daylight saving time in Indiana suggested that a reduced demand for lighting is negated by an increased demand in electricity for heating and cooling, especially in the southern states.

According to the American Academy of Sleep Medicine, the one-hour time shift results in sleep loss and a resultant sleep debt, as well as a misalignment of our circadian rhythms. Road accidents increase, especially on the first two days after the time change, and the rate of fatal accidents is about 6.5% higher during the first week of daylight saving time as compared to the previous or following week.

Perhaps most disconcertingly, several studies have indicated that there is a spike in the rate of heart attacks, an increased risk of stroke, and even a rise in the rate of suicides, following the spring time shift. (A later study challenged the conclusion that there is an increase in heart attacks following DST.)

According to a recent Monmouth University poll, most Americans do not like changing their clocks twice a year, but rather than doing away with daylight saving time, the majority of them would like to make it permanent. In the last five years, 19 states have enacted legislation or passed resolutions to provide for year-round daylight saving time, but these state actions cannot cannot take effect until the federal law changes. Last year the U.S. Senate unanimously passed the Sunshine Protection Act, which would have made daylight saving time the new, permanent standard time, but the bill stalled in the House and expired without leaving the committee to which it had been referred. The bill has been reintroduced during this congressional session, and a companion bill has been introduced in the House, so the fight is not over yet. For now, however, it seems the law—and the controversy—will continue.

Would You Like to Know More?

The National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) has answers to several frequently asked questions about Daylight Saving Time, as well as information about the current DST rules.

The National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) has answers to several frequently asked questions about Daylight Saving Time, as well as information about the current DST rules.

For a list of government documents and other publications at the UNT Libraries related to daylight saving time, search the subject heading “daylight saving” in the Library Catalog. More titles can be found in the Library of Congress catalog.

Visit the Daylight Saving Time WebExhibit to learn more about the history of daylight saving time, about the reasons for it and the controversies surrounding it, and about how other countries around the world observe—or don’t observe—Daylight Saving Time, often referred to as Summer Time outside the United States.

Timeanddate.com also has a helpful compilation of articles about Daylight Saving Time, including tips on how to minimize the health risks encountered when we shift the clocks forward, and a chart summarizing how DST is observed around the world.

Share Your Thoughts

What is your opinion of Daylight Saving Time? Has it affected you in a positive or a negative way? Would you like to leave our government policy as it is, change the days we observe DST, see DST go away completely, or perhaps extend DST hours through the entire year?

Article by Bobby Griffith.

Photos from Library of Congress: http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2002722591/ and http://www.loc.gov/pictures/resource/hec.13949/

Leave a Reply