The advent of jazz studies at North Texas — diplomatically referred to as “dance band” in early years — met predictable resistance. In an oral history recorded in October of 1978, Gene Hall recalled:

“Generally, they [the music faculty] were antagonistic toward it. There were two or three who were very much in favor of it: Bob Rogers, a piano player, and Frank Mainous, one of the theory teachers. There were two or three who were very much in favor of it because they had played professionally, and they knew what it took to get along in the world…”

One colleague, while making clear he had no personal animosity toward Hall, but simply did not believe jazz belonged in the university, took his concerns to President W. Joseph McConnell. Hall described the outcome, quoting the other faculty member:

“I told the president … Y’know, I’ve just come back from a national meeting, and every time I introduced myself as being from North Texas, the reaction is, ‘Oh, that’s where you have the jazz program! Tell me about it!’ And then I have to go to the trouble of telling them we also have an orchestra, and an opera, and all these other things that make the School of Music. And the president says, ‘Well, if you’d get off your ass and do something, you wouldn’t have to do that, would you?’”

In an oral history recorded in March of 1977, the Dean of the School of Music in those years, Dr. Walter Hodgson, explained that President McConnell had taken a keen interest in academic jazz, asking: “Hodgson, how is it that you have a course on music in the Middle Ages, you have a course on music in the Renaissance, Baroque music, music of the Classical era, Romantic music, contemporary [classical] music, but you don’t have any at all that deals primarily with that one segment of music for which America is most famous: jazz!”

Others in the School of Music continued to hound Dr. Hodgson after the establishment of the program, until he called a meeting of all music students and faculty in response to the uproar. Hall had no idea what to expect from the meeting, but Hodgson told his faculty, as quoted by Hall:

“Ladies and gentlemen, we have a music department here, and part of our job is to teach music for a variety of purposes and a variety of people … Now, I’ve had a lot of complaints about the jazz program we have here…”

According to Hall, Hodgson cited the uniquely American nature of jazz, and maintained it was “part of North Texas’ obligation to prepare people in this field.” Hodgson finished: “I want you to know — all of you — that this program is here to stay. There’s no use in you wearing out my carpet coming into my office and complaining about it.”

The program continued into the late 1950s, when Gene Hall took a job at Michigan State University, preceded by Walter Hodgson, who hoped to have Hall found a similar program there. Replacing Hall was his good friend and former housemate, Leon Breeden.

The mid-century years in Denton and Fort Worth produced a constellation of three closely linked, high-achieving musicians: Gene Hall, Leon Breeden, and Don Gillis. When Gillis moved to Chicago, and then to New York to work for NBC, ultimately as a producer for the NBC Symphony Orchestra under Arturo Toscanini, it was Hall who took his position at the radio station. Both Breeden and Hall discussed prospective employment at NBC with Gillis before other circumstances intervened; such was their caliber as musicians.

Breeden, born in Guthrie, Oklahoma in 1921, seemed destined for a career more similar to Gillis’ than Hall’s, having directed bands at Texas Christian University in Fort Worth, studied at the Mannes School of Music, composed large-ensemble works, and arranged for the Cincinnati Pops Orchestra under Thor Johnson. Breeden was turned down for admission to Juilliard — surely a disappointment at the time, but a minor setback in the grand scheme of things.

Family circumstances prevented him from joining Arthur Fiedler as his chief arranger in Boston, and Breeden was directing bands at Grand Prairie High School, near Dallas, when the offer came to take over at North Texas and direct what was then the Two O’Clock Lab Band, moved to its well-known One O’Clock start time shortly after Breeden took over.

The same resistance to jazz with which Gene Hall contended was waiting for Breeden. The transition was so rocky that he considered submitting his resignation after two weeks, and even wrote up a letter to do so after receiving a large amount of hate mail and even late-night phone calls! Breeden fielded the same withering criticism, including warnings that he was risking his soul to eternal perdition by directing the lab band at North Texas.

Breeden was determined not to hand any ammunition to the program’s detractors, and moved pre-emptively to avoid some of the “jazzer” stereotypes among his musicians. Even goatees were forbidden in an effort to buck the stereotypes; the jazz musicians needed to surpass their traditional counterparts to prove themselves as equals, and there were enough challenges as it was without piling on unnecessary battles of appearance and behavior.

Within a few years, however, the introduction of Breeden and Stan Kenton to one another at the National Stage Band Camp began a long and mutually beneficial working relationship. Other successes soon followed, including a State Department-sponsored tour of Mexico in February of 1967, and a concert at the White House in June of that same year, joined by Duke Ellington and Stan Getz, for President and Mrs. Lyndon B. Johnson, and the king and queen of Thailand.

Breeden kept up as exhausting a schedule as his health would allow. On an evening in February of 1968 when he had returned exhausted from a band clinic in Louisiana, his younger son, Danny, was killed in a hit-and-run accident at the age of 19. In a scrapbook among his papers, Breeden notes on an item from the day before Danny’s death: “This was my last totally happy day on this earth.” Years later, Breeden spoke of his regret at having not spent more time with Danny during those busy years.

Amid such profound grief, Breeden continued working with the band in preparation for its appearance at the MENC Conference in Seattle [Music Educators’ National Committee, now the National Association for Music Education], to be held in March of 1968, in front of over 3000 of America’s top music educators. As they waited to play, one band member told Breeden: “Tell them not to open that curtain. We’re going to blow it open in memory of your son Danny!”

Whatever prejudices about jazz and education that the audience may have harbored before the concert, the One O’Clock Lab Band obliterated them. Here was a band that was not only competent, but head and shoulders above many classical virtuosi, and probably most of the members of the audience as well. The combination of technical proficiency, ensemble sense, and the emotional range of the program were such that the One O’Clock Lab Band gave the first encore performance in the history of concerts at MENC conferences. One can only imagine the ripple effect as those directors and administrators returned home to tell what they had seen in Seattle.

Breeden himself wrote in his autobiography:

“It was wonderful to receive letters from many parts of the United States from administrators who said in effect: ‘After hearing your band in Seattle, how can we get such a program started at our school?’ I wrote and gave them the best advice I could, namely that it will take a strong desire on the part of many people and also must be given strong support by your administration if your program will succeed! This always reminded me that at our school we would not have survived if the desire had not been so strong on the part of all of us. I felt in summation that we succeeded in spite of and not with the help of many who could have helped us but did not.”

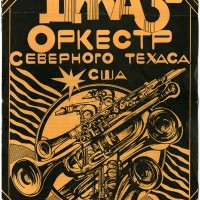

Breeden and the Lab Band only continued toward greater successes, playing with countless jazz legends including Thad Jones, Ella Fitzgerald, Phil Woods, Tony Bennett, and Dizzy Gillespie. The band undertook a European tour in 1970, and in 1976, toured cities across the Soviet Union during the U.S. bicentennial – including Moscow, St. Petersburg, Volgograd, Baku in present-day Azerbaijan, and Yerevan in present-day Armenia. Surely, no one by that point thought that they could bully the program out of existence, as others had tried in the early years.

Upon Breeden’s retirement, Neil Slater took over direction of the One O’Clock Lab Band, and successes continued both for the band as a whole, and for dozens of individual members who have distinguished themselves as studio musicians, in elite jazz ensembles of the U.S. Armed Forces, and in top bands like those of Stan Kenton and Maynard Ferguson. It is also a part of Breeden’s legacy that UNT, as an international destination for jazz studies, became home to both the Kenton and Ferguson bands’ libraries, along with numerous other jazz collections including the Willis Conover Collection, and Breeden’s own extensive archives.

The many aspects of Breeden’s legacy continue to fulfill his wishes, expressed in an oral history also recorded in 1978: “I have got to believe that there are some people, somewhere, that do care, and will fight for jazz education, and do realize that what we’re doing, we can hold our head up and not have a jazz musician feeling that he’s got to be a fourth-class citizen … I’ve gone through those put-downs my whole life, and if we can help eliminate that, my life will not have been in vain.”

[Text includes excerpted presentation notes for “Blow the Curtain Open”: How Gene Hall and Leon Breeden Advanced the Legitimacy of Jazz in Music Education,” by Maristella Feustle, January 11, 2014.]

– By Maristella Feustle, Music Special Collections Librarian

- March 18, 1968: Music Educators National Conference concert at Seattle Opera House

- Leon Breeden in 1959.

- Custom cowboy boots made for Leon Breeden to wear on the 1976 Lab Band tour of the Soviet Union.

- Color Program from Lab Band’s 1976 tour of the Soviet Union

- Leon Breeden and the 1967 UNT Lab Band with then first lady Lady Bird Johnson.

- Dr. Walter Hodgson, former Dean of the UNT School of Music

Kathy McFarland

Looking forward to reading this blog!

Bruce Collier

Our 1961, 90th Floor Records LP, which on reprint became a CD that we titled ‘theRoadtoStan’, was Leon’s first recording.

It was also perhaps part of the official name change of Gene’s ‘’Laboratory A Dance Band’ to the ‘1 O’Clock Jazz Band’.

I had a need to record jazz, beginning in the late 50s.

I approached Gene Hall and received permission to record his last NTSC spring concert…which is how it all began.

There’s more trivia to all that but for now maybe you’ll add this to your notes.

KEVIN COX

Why should we celebrate when, judging from the photos, there are few women and no African-Americans in your photos? Don’t you know that jazz is African-American in origin. Pitiful

Ed Soph

We blew the roof off of the auditorium at the MENC conference in addition to the curtain!

Joe Eckert

I’m so proud to have been a member of Leon’s last 1:00 Lab Band. I only realized years later what a significant accomplishment that was. Still the best program in the world!

Joe Eckert

Former Director

USAF Airmen of Note