Local Archives, Global History: Post 4 by Chandler Hall

Many famed musicians have passed through the music program at the University of North Texas (UNT), but has anyone ever heard of UNT’s accountant-to-organist pipeline? One alumnus who came down it was Robert R. Miller, who graduated from what was then the North Texas State College (NTSC) in 1950 with a bachelor’s degree in business administration. Boxes in UNT Library’s small Robert R. Miller Collection reveal his unique career path: accountant by day and organ consultant and substitute organist by night—or by Sunday. Miller may have been the only accountant-organist in the area at the time, but he was far from the only organ consultant in the Metroplex. For instance, famed musicologist and organist Helen Hewitt supervised the renovation of the Möller Organ in the UNT Main Auditorium, and Robert Anderson, Chair of Organ Studies at Southern Methodist University, acted as consultant on several organs, including St. Stephen’s United Methodist Church in Mesquite and First Presbyterian Church in Dallas. How could Miller hope to compete with these pedigreed, well-known, and highly credentialed figures? His archival traces offer some clues.

In an urban area chock-full of professional musicians with enough degrees to fill a stadium, Miller spun his amateur status as an asset. By positioning himself outside of institutions, he demonstrated to his clients that he was above the politics of the organ world, independent and unable to be bought. His integrity became his selling-point. By focusing on his character, Miller was able to skirt around the subject of his credentials (see figures 1-4).

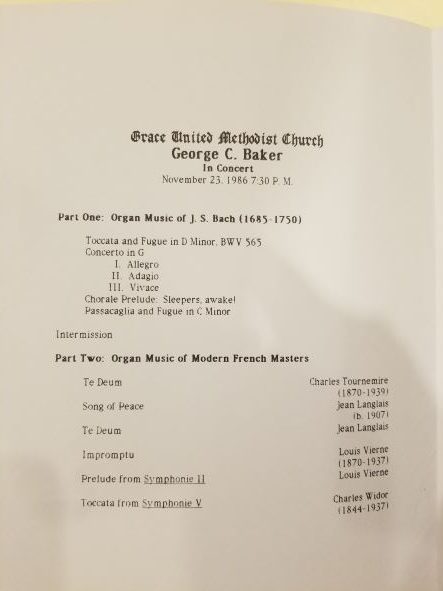

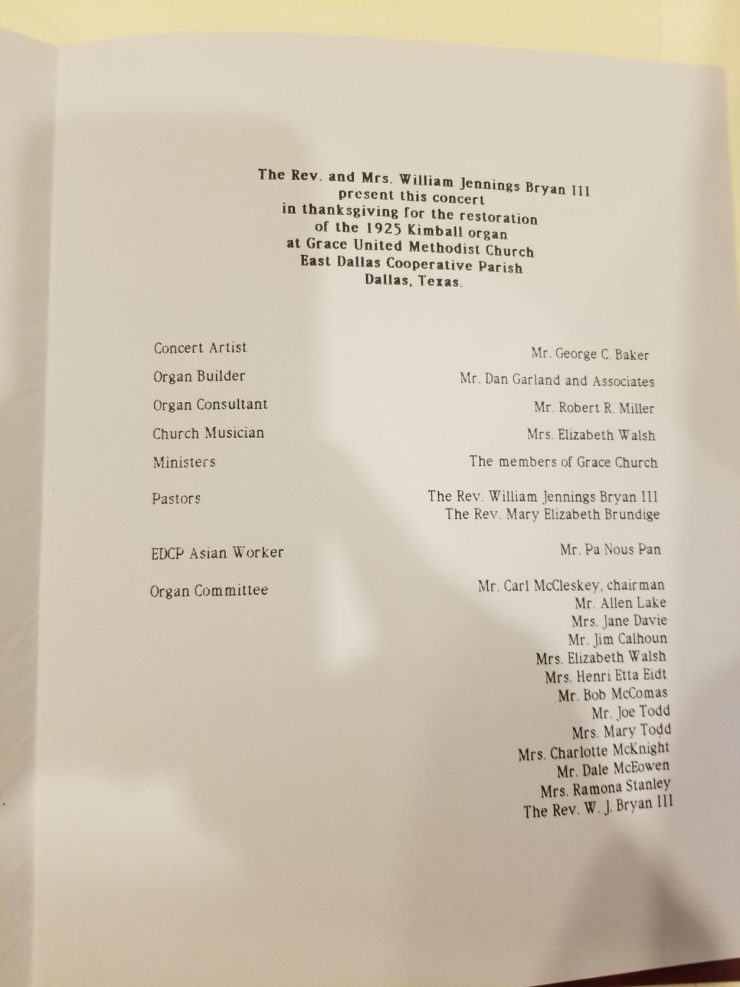

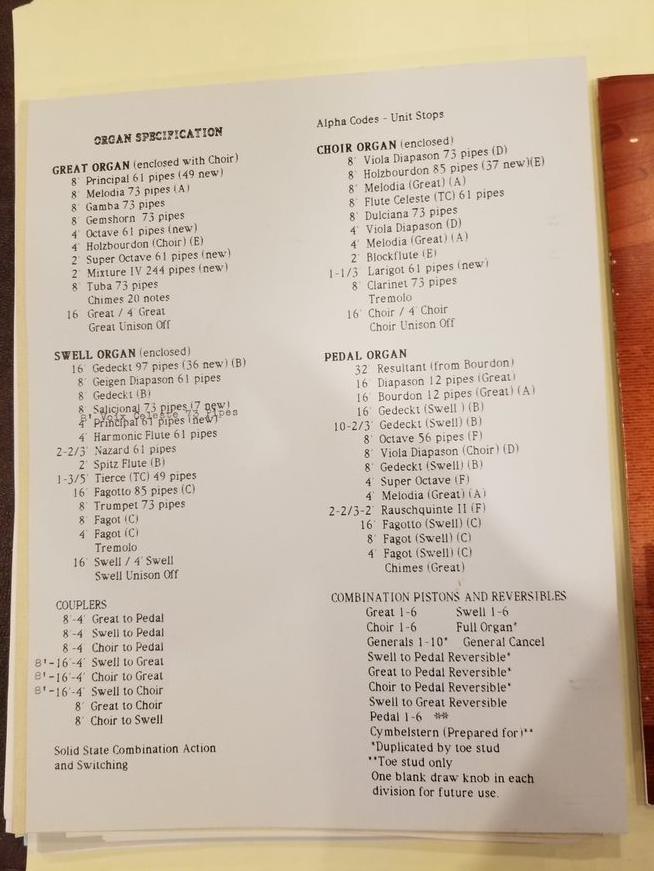

Figures 1-4: 1986 Recital program for the dedication of the restored 1925 Kimball Organ at Grace United Methodist Church, Dallas. Miller was the organ consultant for this project (box 1, folder 11).

Take, for instance, this response to a 1951 letter in which a woman asked for advice about her church’s organ. In the letter, Miller reaffirms that if he were hired as a consultant, he would ensure that the church receives a well-designed organ. He goes on to cite his non-musical career and his independence from builders as assets:

“Yes, I am an Organ Consultant. This type of work is in addition to my regular work at the Magnolia Petroleum Company. As you can well realize, one could not hope to make alliving [sic] at this sort of thing since the calls are few and far between. The reason I do it is that as an organist and a great lover of the organ, I want to help churches obtain the most and best for the money they have to spend… I know of several instances where a church might of [sic] had a better organ if someone that knew about such matters had been called in to go over the plans, rather than just let an organ man or company rebuild the organ as it was.”

In this letter, Miller glosses over his qualifications. By claiming to know of “several instances” in which a church would have benefitted from a consultant, he comes across as knowledgeable without needing to acknowledge his relative lack of formal training. Additionally, by mentioning that consulting is not his main career, Miller implies that he is not in the pockets of any business that would incentivize him to deliver an inferior product. According to Miller, his supposed interest was the church, not the industry.

Figure 5: Miller’s business card from Tellers Organ Company (box 1, folder 18).

Of course, one does not need certain formal credentials to be proficient in an area of expertise; earning a music degree is not the only way to learn music. Although Miller did take some organ coursework at NTSC, he also took lessons before college, played substitute organ at various churches around the Dallas area, and had a (possibly brief) stint as the Southwest Representative for the Tellers Organ Company based in Erie, Pennsylvania.

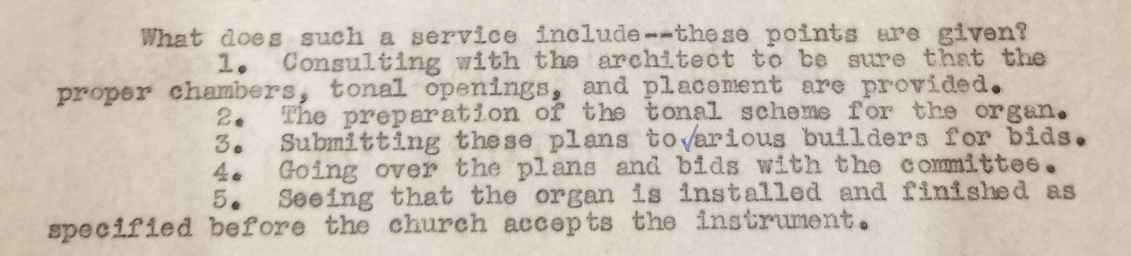

Figure 6: Miller’s duties as an organ consultant as outlined in his letter to Rabbi Annes (box 1, folder 15).

These experiences certainly helped Miller gain expertise regarding how various organs function and sound. Another 1951 letter to Rabbi Pierce Annes of Temple Emanu-El in Dallas, offers further insights into how Miller may have trained as an amateur consultant. In the letter, Miller writes that part of his service as a consultant includes creating tonal schemes (the list of pipe sounds to be used in the organ) and sending them to several organ companies to obtain quotes. Some of these tonal schemes and quotes survive in the collection. In some, a company representative offers Miller suggestions to improve his submission. Other documents in the archive, such as catalogs, design guides, marketing materials, and tonal schemes from hundreds of organs, likely served as reference materials for Miller as he planned projects for his clients. Even as Miller professed his independence from builders in his private correspondence, he clearly relied on them as part of his training.

Miller’s attitude toward institutions was quite different when his audience was public facing. For instance, a worship bulletin at First Presbyterian Church, McKeesport, Pennsylvania, includes a brief biography of Miller’s organ career. This is the church where Miller grew up, and he played substitute organ there just before Christmas 1962, perhaps while visiting family for the holidays. Although it is unclear whether the biography of Miller was written by him or by someone on his behalf, it emphasizes his accreditation as tied to institutions, including NTSU and the American Guild of Organists (AGO). It is not unusual for biographies such as this to list a performer’s musical pedigree and awards, but Miller’s sole accolade by 1962, a “Service Playing Certificate” issued by AGO, is neither particularly impressive nor necessary, considering that the congregation could judge his skill. Rather, the biography is a testament to Miller’s status as a professional on the periphery. By engaging with rhetorical conventions of the profession, Miller attempted to “fit in” as a bona fide musician despite struggling to fill the template. This is not to suggest that a musician needs a music degree or prestigious awards. Rather, the biography highlights the disparity between Miller’s training and what the field and the public expected.

This disparity is at the fore in a 1977 report on the NTSU Möller Organ. Miller compiled the report but concluded it with a reflection on his own qualifications: “Some may wonder why a B.B.A. graduate of N.T.S.U. is writing the survey of the organ instead of a music student or graduate.” Indeed, Miller’s path is curious. His parallel work in accounting, organ consulting, and organ performance forms an unlikely combination, and he capitalized on thwarted professional expectations to brand his identity.

Leave a Reply