Local Archives, Global History: Post 6 By Matt Darnold

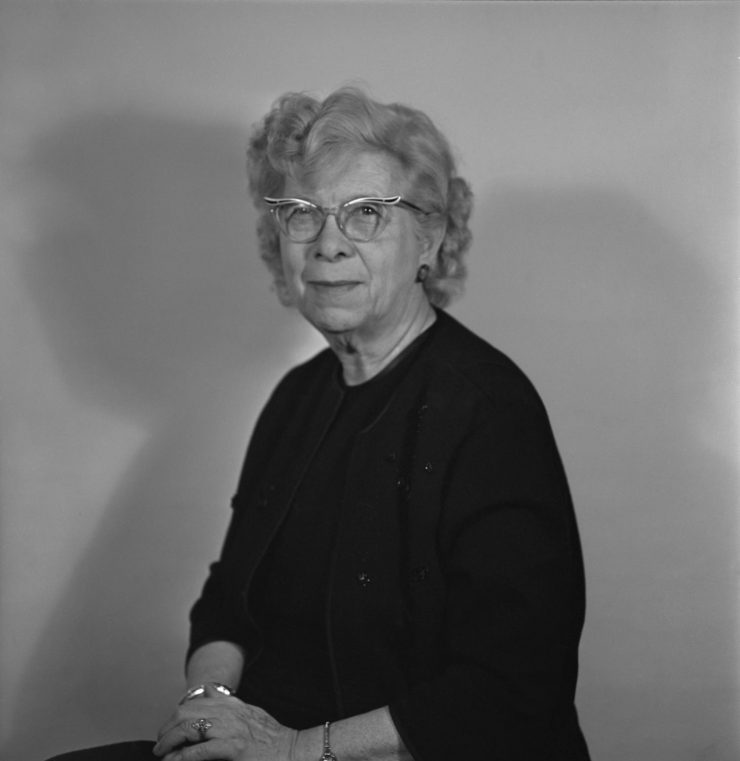

This two-part series will first demonstrate Dr. Helen Hewitt’s commanding place as a woman in musicology, taking a special interest in her time in Paris, which was an integral part of the shaping of the UNT Music Library as it is known today. The second post will chronicle Hewitt’s relationships as a performing organist, and her dedication to UNT’s auditorium organ that almost caused her some legal trouble. Throughout both, one will readily see the lasting impression Hewitt has had on the university and on the field of musicology as a whole. She maintained a number of personal and professional connections across several academic fields and as a result, wielded a degree of influence and reverence that women have not been reflected as having in most histories of academia or musicology as a discipline. Hewitt made a name for herself during American musicology’s early years, and her letters demonstrate that success and her role as a helpful and kind scholar who was a resource to her university and her discipline.

“Dr. Helen Hewitt… is one of the outstanding scholars of the faculty and has made her influence felt far beyond the confines of the School of Music or even of the college. Two years ago she was President of this chapter of AAUP (American Association of University Professors). She has held many offices in our local chapter of AAUW (American Association of University Women). She is the perennial Chairman of the Graduate Music Committee… She has been nominated for presidency of the AMS for this next year.”

This quote from Dean Walter Hodgson to the Vassar College Vocational Bureau comes from the various correspondences found in the University of North Texas Helen Hewitt Paper Collection. It characterizes Hewitt as an influential and involved scholar who even during early years at UNT was making a name for herself both in her department as well as the field of musicology. Hewitt’s robust correspondence reveals that her knowledge and expertise was sought in the field. There are several letters asking her opinion on anything, from doctoral students, whom she had never met, manuscript transcriptions, to personal friends asking for her thoughts on other scholars who were being considered for university positions across the country.

One correspondence that is particularly telling of Hewitt’s influence took place between herself and Hodgson from Fall 1947 to Summer 1948, which coincided with her Guggenheim Fellowship in Paris. Hewitt, at this time, was just being made a full professor in the School of Music at the North Texas State Teacher’s College, later to be known as the University of North Texas, where she had taught since 1942 while finishing her dissertation. These letters contain a mixture of personal and professional details ranging from concerns about the organ studio and the next year’s course schedule, to her living arrangements in Denton and membership in the French Musicological Society as a “foreign member.” Hodgson and Hewitt seemed to have a warm working relationship. Hodgson turned to her with a number of concerns and ideas. Hewitt wrote in a May 1948 letter that she “never wanted nor sought an administrative position… because [she] dislike[d] making judgments of even the most trifling consequences.” She had no problem, however, voicing her opinion on any and all matters in her letters to Hodgson. In the same letter she voices her concerns about the organ studio’s size, hoping to reduce it from 50 to 10 students. This correspondence is also one of the few in which we have Hewitt’s letters along with those she received, allowing us to recapture some essence of Hewitt’s own voice rather than just those who wrote to her.

The highlight of Hewitt’s Paris letters is perhaps when Hodgson tasks her with scouring second-hand book stores in Paris for material to fill the school’s expanding Music Library, especially its organ collection. This quickly became a more general search for music, from opera scores to reference material, such as the well-known works of nineteenth-century Belgian musicologist and critic François Fétis. Hewitt seemed to embrace this task hardily, based on the enthusiasm displayed in some of her early letters, or she at least took it on eagerly as a young professor who was still establishing herself in her position at NTSC. A notable amount of money was granted to the Music Library at this time with around $700 eventually being sent to Hewitt in various installments to cover purchasing costs. There are also lists of the materials she acquired and shipped back to north Texas that likely remain in the library to the present.

Hewitt became weary of this undertaking as time passed. In a March 1948 letter She sent an “S.O.S” in which she strongly tells Hodgson to get his “library committee together,” so she knew what books and scores to secure as she felt “uncertain” in making these decisions herself. She also forwarded a great deal of information on several possible purchases that would in her opinion benefit the library, such as three volumes of Couperin’s Pieces de Clavecin, all the volumes issued by the French Musicological Society, or “the Fitzwilliam Virginal Book.” Around April 1948, Hodgson recommended that Dr. Doty of the University of Texas write to Hewitt for “a list of musicological items that NTSC was not going to purchase.” Hewitt showed her frustration to Hodgson in her response to him written on April 13, 1948 in which she chides him for not just crossing off the items of her previous list and sending it to Dr. Doty and says that “he can write them directly if he wants.” Here we find Hewitt in a relatable situation as a person overwhelmed by professional responsibilities while attempting to complete her own research, showing us that although she was a renowned and accomplished researcher and educator and this work helped to advance the school’s music library, academia had a number of challenges and obstacles that we still find today in the way of young scholars.

Despite these early obstacles, Helen Hewitt was determined to fight for the best possible education for both her musicology and organ students. As an organ professor, she oversaw the maintenance and specifications of the school’s organ even during her research in Paris. In 1947, Hewitt received a phone call from Denton, which at the time was quite an undertaking, concerning the organ in the main auditorium. Hewitt had long indicated the need for a new organ console, and while in Paris, she corresponded with Dean Hodgson to guide the school’s negotiation and approval of a repair contract with the Möller organ company. This project awaited upon her return to Denton and presented many of its own unanticipated challenges for Hewitt as she established herself at NTSU.

Editor’s note: Stay tuned for more research on Hellen Hewitt in the next post by Emma Wimberg.

Citation:

[Dr. Helen Hewitt], photograph, 19XX; (https://texashistory.unt.edu/ark:/67531/metadc977101/: accessed April 12, 2022), University of North Texas Libraries, The Portal to Texas History, https://texashistory.unt.edu; crediting UNT Libraries Special Collections.

Leave a Reply