LOCAL ARCHIVES, GLOBAL HISTORY: POST 8 BY EMMA WIMBERG

While Dr. Helen Hewitt was on her Guggenheim Fellowship in Paris, Hewitt’s mother, worried about Hewitt and how her time was going, wrote to her from the states to ask if she had found a women’s group with which to engage. Hewitt replied:

“I asked [a French colleague] about women’s societies; and he said they had a group of women who met to sew, etc., Tuesday afternoons at the church. Mother, do you really think I should take more afternoons off for this sort of thing, when I have so much to do? It does seem as though there are enough women who have nothing to do afternoons who can take care of such matters. I feel as though my time should be spent where it will do the most good – – in my own work.”

Hewitt was firm in her conviction about what she wanted in life: to establish herself as an organist and as a musicologist, making materials more accessible for others to study while publishing her own contributions to the field. She did not let the ideas about what a woman should be doing impact what she was going to do. This conviction—and the respect she earned through her work and actions—extended past musicology and into performance. During her time as a professor, Hewitt taught musicology classes and organ lessons. She studied under many famous organ teachers and was an incredible player in her own right, being highly sought after as an organist. This post will explore Hewitt’s reputation among performers and her dedication to the organ, and specifically to the organ studio at NTSU, its students, and the instrument the auditorium houses. This last point would eventually place Hewitt in a difficult position, where speaking her mind in the interest of attaining the best possible instrument for the university caused the Möller organ building company to consider filing a lawsuit against her for defamation.

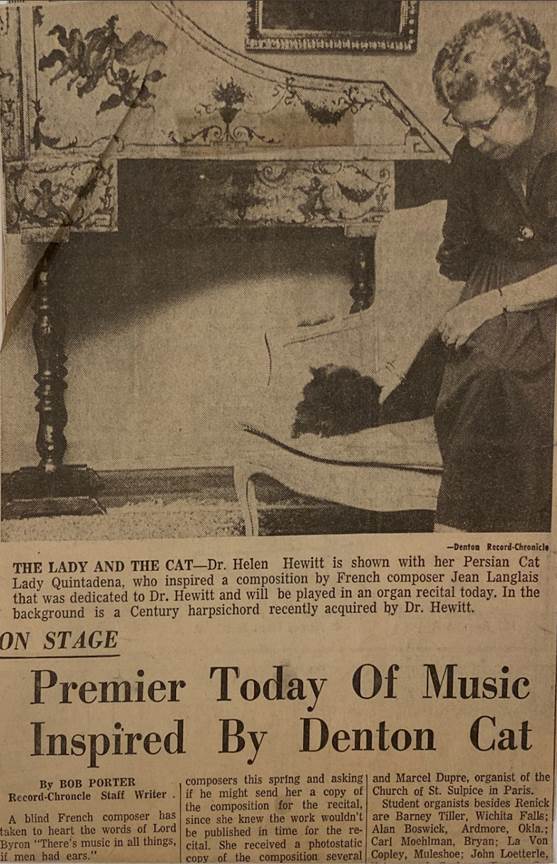

In the mid-twentieth century, French organists commonly toured America to showcase their talent, which allowed Hewitt to forge a strong friendship with the famed organist and composer Jean Langlais. During one visit to Hewitt’s Denton residence, Langlais spent many hours playing with Hewitt’s cat, Lady Quintadina, named after an organ stop and her kittens. He became infatuated with them and not only remembered to call on the cat’s birthday, Valentine’s Day, but also wrote a piece inspired by the Lady and dedicated it to Hewitt. The movement in his American Suite was thus titled Scherzo: Cats and was first performed before its publication on the Möller organ in the North Texas State University auditorium that Hewitt herself had worked so hard to improve.

Figure 1: Newspaper clipping captioned “The Lady and the Cat.” University of North Texas Music Special Collections. Helen M. Hewitt Papers, 1887-1976, Series 1: Papers, Box 428, Folder 5.

The story of Hewitt and the Möller organ began not long after her hiring at the university. There were few organs on campus and 50 organ students. Hewitt began trying to shift the studio to be smaller and more focused, and for these changes to take hold the students needed a quality instrument with which to work. In the mid-1940s Hewitt started asking for a budget to fix the Möller organ in the auditorium, the only performance instrument used during her tenure. However, the dean at the time was more focused on furthering the vocal department rather than the instrumental one, and had turned down the previously proposed repair contract even after it had been looked over by Möller. Once Hewitt left on her Guggenheim to Paris, the dean’s retirement and the department’s regime change brought instrumental music up the ladder of priorities. The new acting dean, Dr. Walter Hodgson, who later became the dean, immediately sought out Möller to finalize a contract for the construction of a new organ console.

In March of 1948, the university signed a final contract with Möller Co. for $26,400 worth of work to be done on the new organ, including a new console, new stops, and general repairs. Hewitt remained very hands-on throughout the entirety of the re-build. She constantly gave her input on what stops she wanted included and how she wanted the instrument to sound upon completion. Correspondence from Hewitt lists specific requests she had for the instrument, requests that were not all filled.

Just as construction on the organ came to a close in March of 1949, Hewitt fell ill and privately sought treatment for her ailment. During this time, there is a sizable gap in her usual letter-writing habits to the point where there are many letters from her close friends inquiring as to if she is angry with them because they had received no reply to subsequent letters over the course of a few months. This gap leaves much to be wondered concerning the final implementation of the organ and Hewitt’s relationship with the builder.

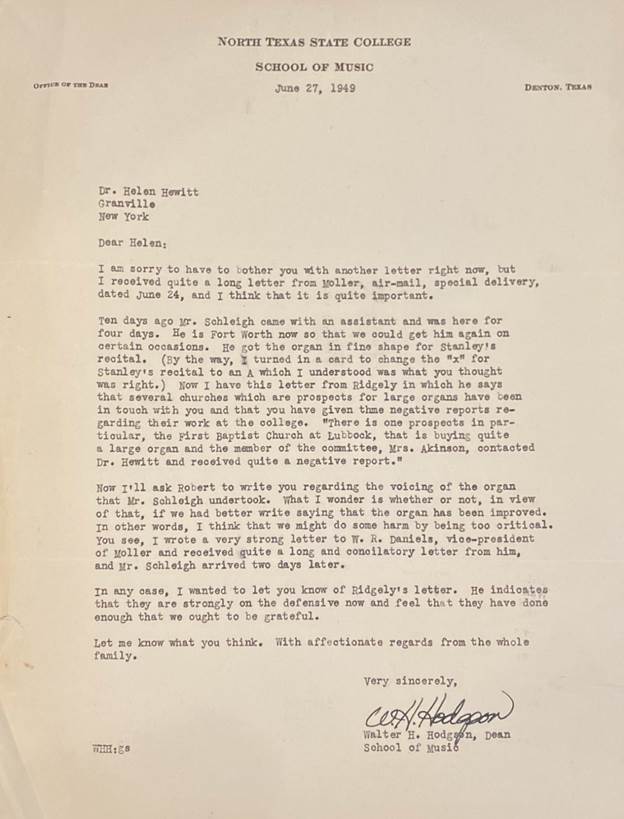

If Hewitt was such a highly respected and loved figure among the university’s music department, then why did Dean Hodgson receive a disgruntled letter about her from a well-known organ company? There is documentation of Möller considering legal action against Hewitt, but why? Many of the letters between the two concerning her displeasure are not recorded in our archives, but there is mention of the feelings the two parties had for one another. Walter Hodgson, the dean who had overseen the project, wrote to Hewitt about a disgruntled letter he had received from the Möller company (see figure 2). It reads:

Dear Hellen:

I am sorry too have to bother you with another letter right now, but I received quite a long letter from Möller, air-mail, special delivery, dated June 24, and I think that is quite important.

Ten days ago Mr. Schleigh came with an assistant and was here for four days. He is Fort Worth now so that we could get him again on certain occasions. He got the organ in fine shape for Stanley’s recital. (By the way, I turned in a card to change the “x” for Stanley’s recital to an “A” which I understood what you thought was right.) Now I have this letter from Ridgely in which he says that several churches which are prospects for large organs have been in touch with you and that you have given them negative reports regarding their work at the college. “There is one prospects in particular, the First Baptist Church at Lubbock, that is buying quite a large organ and the member of the committee, Mrs. Akinson, contacted Dr. Hewitt and received quite a negative report.”

Now I’ll ask Robert to write you regarding the voicing of the organ that Mr. Schleigh undertook. What I wonder is whether or not, in view of that, if we had better write saying that the organ has been improved. In other words, I think that we might do some harm by being too critical. You see, I wrote a very strong letter to W. R. Daniels, vice-president of Möller and received quite a long and conciliatory letter from his, and Mr. Schleigh arrived two days later.

In any case I wanted to let your know of Ridgely’s letter. He indicates that they are strongly on the defensive now and feel that they have done enough that we ought to be grateful.

Let me know what you think. With affectionate regards from the whole family.

Very sincerely,

Walter H. Hodgson, Dean

School of Music

Figure 2: Letter from Walter H. Hodgson to Helen M. Hewitt. University of North Texas Music Special Collections. Helen M. Hewitt Papers, 1887-1976, Series 1: Papers, Box 420, Folder 8.

This letter conveys a friendly scolding tone, where the dean does not truly reprimand Hewitt for her freedom in giving a negative coloring of her interaction with Möller, but gently tries to warn her of the current situation whilst trying to help figure out how to get the situation resolved. He also makes it clear that he has sent a strong letter of his own and that they are in this together.

The next important part of this letter is that Dr. Hewitt did not go around spreading a bad coloring of Möller and their work. Rather, she was asked her opinion, and she gave an honest response. Hewitt had worked hard to gain the respect she had in the musicology and organist communities, and part of this meant being trusted to give sound, honest insight to problems and questions that others had. It would have been incredibly out of character for her to take this opportunity to forge a stronger bond with Möller by recommending them to everyone against her better judgement.

It is also possible that Hewitt’s displeasure with Möller’s services could be from the poor conditions they left the school with while the organ was away being reconstructed. The first practice organ they left in its place began giving the school trouble, and scheduling the time to put a new substitute instrument in the auditorium was a nightmare as well. All of this, while the studio filled capacity at around 50 students. While much remains to be explored on this matter, it is clear that Hewitt wanted to make sure her organ students had an instrument of high caliber on which they could perform, and intended to make this need heard.

Leave a Reply