Written by Sierra Dahl

Willis Library has recently undergone some changes to make the library better equipped to serve students. These improvements include renovations to the building, modern furniture, new reservable spaces, and additional borrowable equipment and materials.

New Reservable Spaces

The first addition to Willis Library is study pods, reservable spaces designed for individual study or studying in pairs. These pods are soundproof, include furniture such as chairs and tables, and have electrical outlets. The pods are located on the lower, second, and fourth levels.

These spaces are convenient for students who prefer more silence when studying. In addition to the pods, on the first floor, there are One Button Studio Spaces, three rooms designed to record video or audio. Pods and One Button Studio Spaces can be booked on the Space Reservations page and the spaces can be reserved for up to two hours each day by currently enrolled students.

New Accessibility Equipment and Materials

There are new offerings of equipment and materials that can be checked out at the Willis Library Service Desk. This collection is called the Willis Library Services Desk Equipment Collection and can be browsed on the Willis Library Services Desk Equipment webpage (UNT Libraries, 2022c). The accessibility portion of this collection includes sensory items and other items that may be of particular interest to those with accommodation needs (UNT Libraries, 2022a). Specific items include C-Pen Readers, magnifiers, assistive listening devices, sensory items, and calculators. Items in this collection are available to any individual with an unblocked UNT Library account.

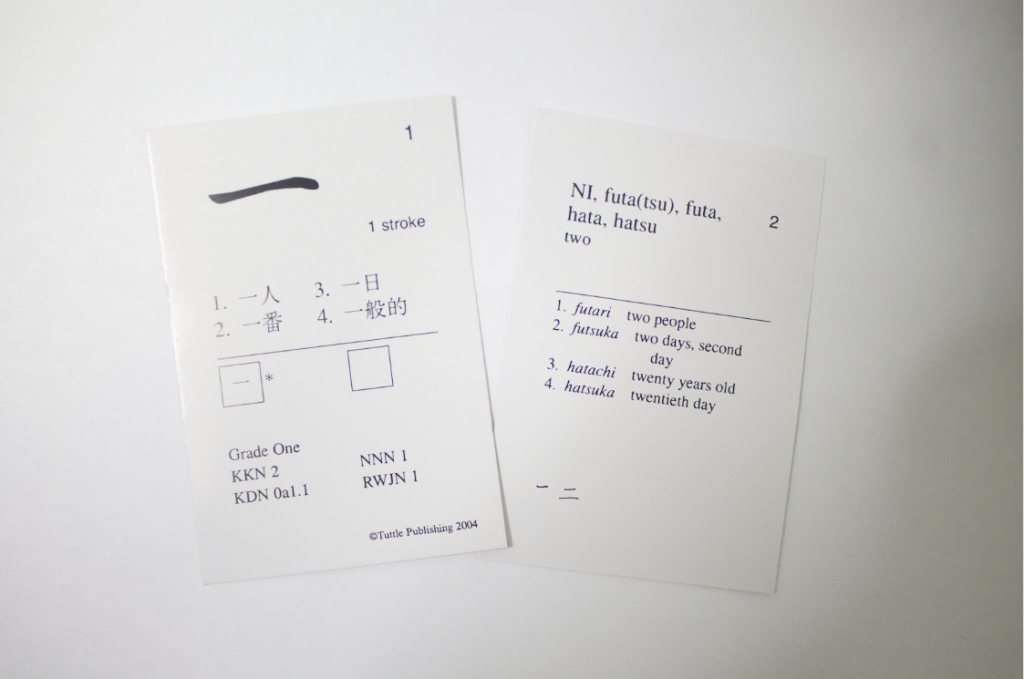

New Curriculum Equipment and Materials

The curriculum portion of the Willis Library Services Desk Equipment Collection includes items that support learning and study (UNT Libraries, 2022b). Specific items in this collection include supply kits, calculators, language flashcards, an electronic translator, a desk light, and a book stand.

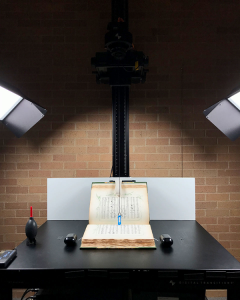

Digitization of General Course Reserves

Course reserves are also being made accessible online to allow better availability to all students. Physical materials in general reserves, which are offered every semester, have been replaced whenever possible by online copies. This change helps to increase access to materials by no longer requiring students to come to Willis Library in person to borrow the course reserves they need.

Space Renovations and New Furniture

Additionally, there have been building updates such as bathroom renovations and the addition of modern furniture. This new furniture includes more individual study furniture and height-adjustable desks located on every floor. The desks can easily be converted from seated to standing desks by pressing the red lever located on each desk’s right side.

Did this blog help you learn about the recent improvements to Willis Library? Let us know your comments! Please contact Ask Us if you have any questions about library services.

References:

UNT Libraries. (2022, February 23). Accessibility Items. https://guides.library.unt.edu/c.php?g=1187058&p=8698146

UNT Libraries. (2022, February 23). Curriculum Items. https://guides.library.unt.edu/c.php?g=1187058&p=8698166

UNT Libraries. (2022, February 23). Overview. https://guides.library.unt.edu/c.php?