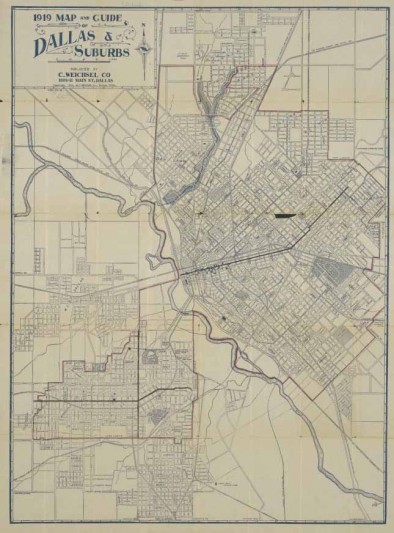

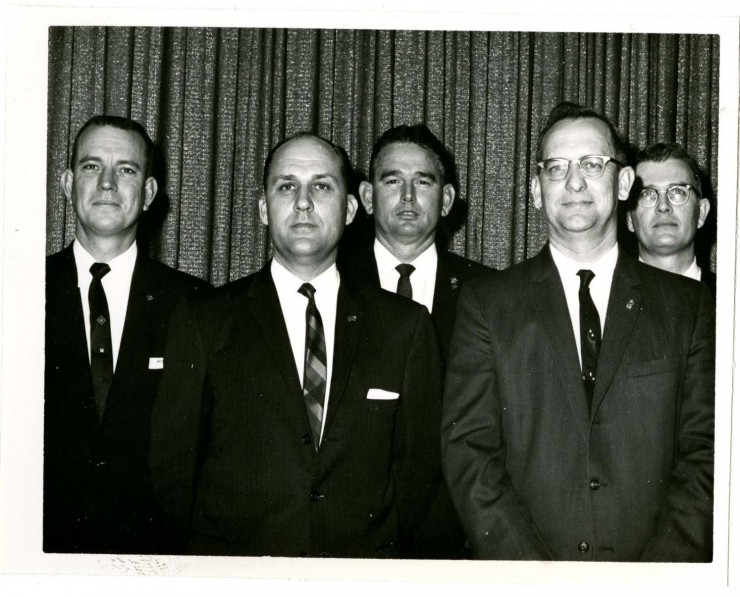

1963-64 TIAA Executive Committee: Frank Miller, M. D. Williamson, F. L. Bay, Benton Broschette, and John Ballard

In 1964, the Texas Industrial Arts Association appointed a new executive secretary to its ranks: Dr. M. D. Williamson, Associate Professor of Industrial Arts at North Texas State University. He was chosen at the annual TIAA conference at Texas A & M University in College Station. Williamson is pictured above, alongside the rest of the 1963-64 TIAA Executive Committee.

Williamson made many contributions to Texas Industrial Arts, including several TIAA Bulletin articles, leading educational workshops, and serving as secretary-treasurer of the West Central Texas Regional Industrial Arts Association. He chaired the 1962 state convention, and was also chairman of the 1962 TIAA Drafting Committee, which wrote the drafting curriculum study for Texas schools. In addition, he served as Vice-President of TIAA in the 1962-63 year, followed by a term as President.

![[Industrial Arts Club], Photograph, 1942; (http://texashistory.unt.edu/ark:/67531/metadc233013/ : accessed August 13, 2015), University of North Texas Libraries, The Portal to Texas History, http://texashistory.unt.edu; crediting UNT Libraries Special Collections, Denton, Texas.](http://blogs.library.unt.edu/southwest-metroplex/wp-content/uploads/sites/14/2015/08/metadc233013_l_UNTA_U0458-096-516-04-400x307.jpg)

[Industrial Arts Club], Photograph, 1942; (http://texashistory.unt.edu/ark:/67531/metadc233013/ : accessed August 13, 2015), University of North Texas Libraries, The Portal to Texas History, http://texashistory.unt.edu; crediting UNT Libraries Special Collections, Denton, Texas.

At the time, TIAA was comprised of 800 teachers and supervisors from public schools and colleges across the state. The North Texas chapter was the largest of the fifteen regional associations. Williamson wasn’t the only North Texan making a big impact on industrial arts education. Dr. Jerry McCain founded the Industrial Arts Club at North Texas State University, and he also served as secretary-treasurer of the North Texas Industrial Arts Association.

Thanks in part to hardworking faculty like these, North Texas became a trusted name in Industrial Arts education. A look at this commencement program from 1950 lists the names of several students who completed a Bachelor of Science program in Industrial Arts. When IA was just beginning to take off, Texas Woman’s College in Denton was known as the College of Industrial Arts for a few years (1905-1934).

The Texas Industrial Arts Association Publications and Records Collection at UNT’s Special Collections offers photographs, publications, and correspondence from 1946 to 2004. Items in this collection illustrate the importance of industrial arts to students, teachers, and their impact on Texas and the Southwest Metroplex.

-by Alexandra Traxinger Schütz