Linda Jenkins

What do you think of when you hear the name ‘Ludwig van Beethoven’?

Maybe it’s the iconic opening figure of his Symphony 5 (think: dundundunDUNNNNNN from a sample of these performances).

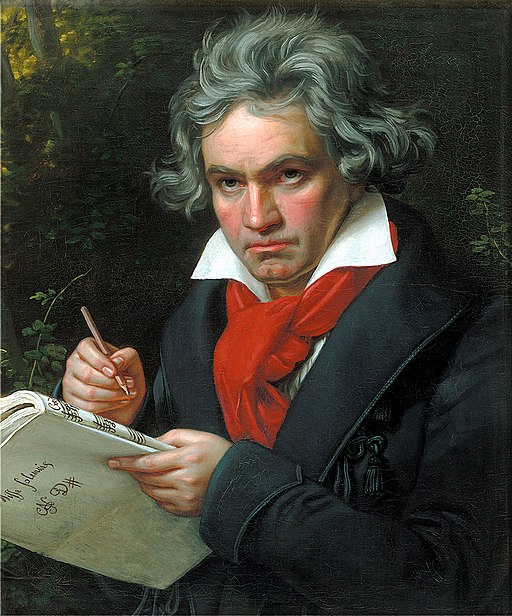

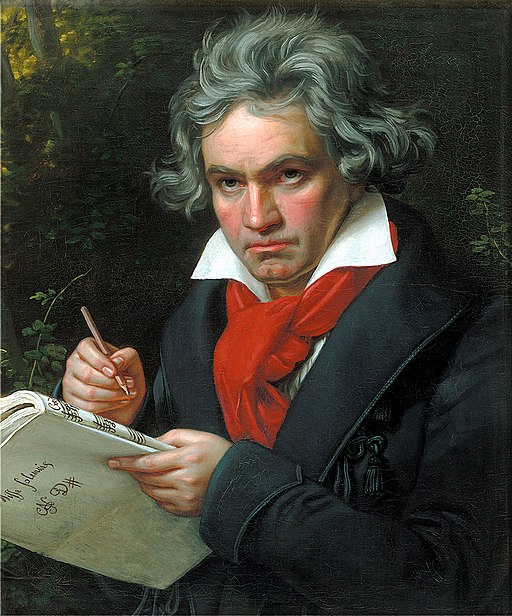

Or his famously thunderous countenance:

Joseph Karl Stieler, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Beethoven is one of the most celebrated composers in Western classical music. In his lifetime, Beethoven enjoyed a privileged lifestyle as the musical darling of Vienna’s aristocracy. Unlike many of his predecessors, such as Joseph Haydn, he was not tied to a royal court and still managed to be financially successful through the support of aristocratic patronage. His contributions to form and harmony across the genre directly inspired composers of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. To this day, Beethoven remains one of the most frequently programmed composers in the United States. In a study of participating orchestras across America from 2000 to 2012, Beethoven was the most programmed composer in all but three seasons. And for the seasons he wasn’t first on the list, it was a close second to Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (League of American Orchestras, 2020).

On the 250th anniversary of Beethoven’s birth, some scholars are examining the mythos surrounding Beethoven and have chosen to recognize Beethoven’s birthday in alternative ways, such as identifying lesser known works of Beethoven and unrecognized works of others (Wilson, 2020).

Regardless of how people are choosing to reflect on Beethoven at his 250th birthday, two and a half centuries later, Beethoven’s body of work still speaks to the concert-going public. What makes his music so impactful? Let’s explore some of his background and musical influences.

Early Life

Ludwig van Beethoven was born in December of 1770 to a musical family in the town of Bonn, Germany. Both his father and grandfather were musicians in the choir of the archbishop-elect of Cologne; so, like most of the working class at this time, Beethoven was born into his profession. Beethoven took violin and piano lessons from his father Johann, who hoped his son would be seen as a child prodigy a la Mozart. Johann even passed his son as younger to mirror Mozart’s debut age, a fact that Beethoven himself only found out as a young teen (Biography.com Editors, 2020).

Around 1780, political shifts and new appointments resulted in Bonn becoming a thriving city of culture with a newly established university and an influx of German renaissance literary minds like Goethe – widely considered the greatest German literary figure of the modern era (Boyle, n.d.). It was in this environment that 12-year-old Beethoven became the assistant to Christian Neefe, the appointed court organist and Beethoven’s teacher (Knapp, 2020).

Over the next ten years, Beethoven was able to make important societal connections. The first important family in this network was the house of the late Joseph von Breuning, who hired Beethoven to teach two of their children piano and to perform for a variety of social events. Beethoven acquired a number of wealthy students and patrons through the Breunings, including the Count Waldstein (whose name you might recognize as the dedicatee to Beethoven’s famous Waldstein Sonata, opus 53). Beethoven even composed a ballet score for the Count to pass off as his own composition, although it was well-known to be Beethoven’s work. This ballet ended up being his ticket out of Bonn when, in 1790, London-based composer Josef Hadyn saw the score while staying with the arch-bishop. Haydn was impressed enough that he invited Beethoven to study with him in Vienna when Hadyn returned from his London residency (Budden, 2020).

Beethoven in Vienna

Beethoven received a warm welcome from the Viennese aristocracy, his reputation as a performer preceded him thanks in large part to Count Waldstein who heralded Beethoven as the successor to Mozart. With the support of wealthy patrons for food and lodging, Beethoven was able to fully cut ties with the Electorate in Cologne in 1794.

In his composition studies, Beethoven worked with Haydn on piano, Antonio Salieri for choral composition, and counterpoint with organist Johann Albrechtsberger. In 1795, he performed his public debut recital in Vienna with a program featuring his piano Concerto No. 2, Opus 19, as well as works by Mozart and Haydn. Around this time Beethoven was also able to publish a set of Trios to a long list of subscribers. Beethoven’s symphonic debut in Vienna occurred in 1800 and featured a performance of his Symphony No. 1, a piano concerto, and the Septet (Opus 20) alongside works by Mozart and Haydn (Biography.com Editors, 2020).

Musical Influences

Working in the Breuning’s household, Beethoven was introduced to the literary movement ‘Sturm und Drang’, which is defined by the Encyclopedia Britannica as a “German literary movement of the late 18th century that exalted nature, feeling, and human individualism and sought to overthrow the Enlightenment cult of Rationalism” (The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica, n.d.).

In music, this movement translated to grand and sudden contrasts of tempo and dynamics aimed at expressing vast extremes of emotion. Beethoven’s affinity for improvisation is heavily reminiscent of his study of this movement, as well as the work of C.P.E. Bach.

Other early musical influences came from Bonn’s proximity to the city of Mannheim and the Mannheim Orchestra, the first orchestra comprised entirely of elite players, who had strong ties to Paris. Beethoven supported the French Revolution and greatly admired Napoleon Bonaparte. Beethoven’s Third Symphony was originally dedicated to the French military leader but, upon hearing that Bonaparte had declared himself Emperor of France, Beethoven changed the dedication to “for the memory of a great man”, and renamed the symphony “Eroica” (Budden, 2020).

Heiligenstadt and Beethoven’s Second Period

The turn of the 19th century marks a shift in Beethoven’s compositional style. Around 1800, his writing becomes more nuanced and widens in scope, using large musical forces in new and unconventional ways. Until this point, his works were mostly for solo piano and conformed to the musical forms and rules of the time (Budden, 2020). A major reason behind this shift is Beethoven’s growing realization that he was going deaf. As this illness progressed, his efforts moved from solo performances to composing. He began to avoid public gatherings, confessing in an 1801 letter that he “leads a miserable existence…because [he] find[s] it impossible to say to people: I am deaf.” (Biography.com Editors, 2020). This internal turmoil came to a head in the poignant note Beethoven penned in 1802 while taking a respite in the country village of Heiligenstadt titled “The Heiligenstadt Testament”. Addressed to his brothers, it also outlines a basic will and was kept in a private drawer to be discovered after Beethoven’s death. An excerpt from this unsent letter reads:

“O you men who think or say that I am malevolent, stubborn or misanthropic, how greatly do you wrong me. You do not know the secret cause which makes me seem that way to you and I would have ended my life — it was only my art that held me back. Ah, it seemed impossible to leave the world until I had brought forth all that I felt was within me” (Beethoven; Thackara (Ed)., 1902; 1979).

Beethoven returned home from Heiligenstadt and continued to compose in a fervor. The next period of composition (~1802-1814) is considered his most productive era, producing six symphonies, his only opera (Fidelio), four solo concerti, five string quartets, six-string sonatas, seven piano sonatas, five sets of piano variations, four overtures, four trios, two sextets and 72 songs (Biography.com Editors, 2020).

Beethoven’s Private Life

Financially and artistically, Beethoven was extremely successful. However, in his personal life, Ludwig van Beethoven struggled to maintain relationships with his patrons, fellow musicians, and relatives. He was infamously temperamental, prone to being incredibly defensive, and thus constantly feuded with those around him. Beethoven never married, although he is rumored to have been in love with multiple female students. Upon his death, along with the “Heiligenstadt Testament”, secret letters addressed to the “Immortal Beloved” were found hidden away in Beethoven’s desk. The identity of the recipient is still unknown, and each letter is labeled only by month and day (Biography.com Editors, 2020).

More on Beethoven

We have so much information about Beethoven’s life and musical output thanks to the letters, journal entries, and notebooks left behind after his death in 1827. Want to read more? Here are some online resources from UNT’s online library catalogue:

Beethoven: Anguish and Triumph: a biography by Jan Swafford

Beethoven the pianist by Tilman Skowroneck

Beethoven and the Construction of Genius: Musical Politics in Vienna (1792-1803) by Tia DeNora

References

Beethoven, L.V.; Thackara, W.T.S. (Ed.) (1802; 1979). The Heiligenstadt Testament of Ludwig Van Beethoven: Notes by W.T.S. Thackara. The Society. https://www.theosociety.org/pasadena/sunrise/28-78-9/s28n07p244_the-heiligenstadt-testament.htm

Biography.com Editors, 2020. Ludwig van Beethoven: c. 1770-1827. Biography. https://www.biography.com/musician/ludwig-van-beethoven

Boyle, N, (n.d.). Johann Wolfgang von Goethe. Encyclopedia Britannica Online. https://www.britannica.com/biography/Johann-Wolfgang-von-Goethe/First-Weimar-period-1776-86

Budden, J.M., (2020). Ludwig van Beethoven: German Composer. Encyclopedia Britannica Online. https://www.britannica.com/biography/Ludwig-van-Beethoven#ref21581

The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica, (n.d.). Sturm und Drang: German Literary Movement. Encyclopedia Britannica Online. https://www.britannica.com/event/Sturm-und-Drang

Knapp, Raymond. Ludwig van Beethoven: German Composer. Encyclopedia Britannica Online. https://www.britannica.com/biography/Ludwig-van-Beethoven#ref21580

League of American Orchestras, (2020). ORR Archive. https://www.americanorchestras.org/knowledge-research-innovation/orr-survey/orr-archive.html

Wilson, J. (2020). Celebrate Beethoven by resisting ‘Beethoven’: how to programme concerts for the great composer’s 250th anniversary. Classical Music from BBC Music Magazine. https://www.classical-music.com/features/composers/celebrate-beethoven-by-resisting-beethoven-how-to-programme-concerts-for-the-great-composers-250th-anniversary/

Edited by Kristin Wolski