Mattie Tempio

Introduction

The sounds of rain and water are more than simple sounds: since the beginning of humanity, rain has been the center of our lives, making everything from food to electricity possible. As such an important part of world culture and human history, it has been explored by countless composers, conveyed in countless media formats. It has been portrayed through simple recordings and in programmatic music. However, with the rise of interactive computer music, there is yet more within the realm of water to explore. My thesis, Rainpiece, aims to create a modular, interactive soundscape as a basis for a flute, viola and harp trio, using pre-recorded fixed media and live diffusion to create a single, synthesized experience. The work for this piece began more than a year ago, though in the last semester I have made great strides towards accomplishing my goal. These steps included creating unique notations to convey my ideas, studying concepts behind soundscape and memory, and experimenting with granulation frameworks in the max/MSP software.

Technical Aspects

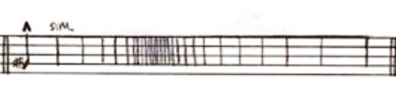

As this thesis focuses on the interaction between water sounds and instrumental sounds, the notation is a key part of a performer’s understanding of the work. The score structure is divided into solo parts, for solo performances, and trio parts, used for optional trio performances. This piece uses proportional notation, though also includes fast-paced, rhythmic passages that rely on accelerando and decelerando. To keep the unmetered, improvisatory feel to the piece, I chose to use beamed, headless stems that would vary between 1 and 10 centimeters apart.

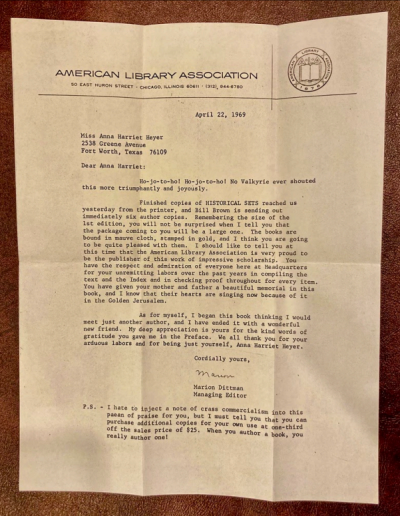

Fig.1. Sample rhythmic passage, from mvt. 1, Rainpiece.

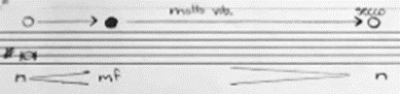

The actual note(s) the performer could choose would appear either on the first stem, or in parenthesis just before the start of the passage. This leads to the concept of notating the air to pitch spectrum (available only in the flute part, for obvious reasons). This notation has appeared in my previous works, including 2022’s Interrupted meditation, 2021’s Strange times in the void Space, 2018’s Remnants of the Veil Nebula, and Juno and the Voyager. It works on multiple instruments, and most performers understand it and can replicate the requested sounds quickly.

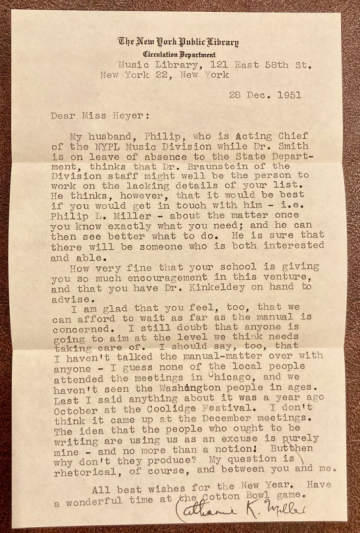

Figure 2. Air to pitch notation.

Finally, this score explores multipath modular notation, inspired by Terry Riley’s In C, Earle Brown’s Available forms and Dr. Andrew May’s Wandering through the same dream. This means that rather than employing a fully-linear score, the performer(s) have individual modules that they may choose from. In the trio parts, this means that vertically-displaced boxes show the performer a variety of options they may choose from, when artistically called for. This aids not only in creating an open, adaptable work that invites performers to shape the work, it also frees the performers from a rigid, structured work that might hinder in understanding and working with the electronics.

The electronics for this work have been assembled in the Reaper DAW (Digital Audio Workstation) and max/MSP (Now commonly referred to simply as Max). I used Reaper to assemble the fixed-media portions of the work, while my work in Max has taken far more time and research, focusing on granulation. First, I have explored a few formats and models for granulation: the first is a digital instrument I assembled over the last year, using Dr. May’s granular composition tools as a base. With Dr. May’s aid and guidance, I learned how to adapt the granulation tool, meant primarily for pre-recorded sound, into a tool that can granulate live sound. While this granulation tool has served me well, I wished to understand my other options, and see if there exists a granulation tool that would fit my needs better, and provide a more streamlined interface. For that, I tried Chris Poovey’s Grainflow max package. While Chris’s work is well done and worthy of further exploration and analysis in its own right, I have found it far more than what I need for the scope of the project. Most likely, the granulation aspects of this thesis will end up as some mixture of the two levels of complexity, as the granulation is only one aspect of the work. Of course, there are many more aspects of the work to discuss, such as scripting, modularity, and a user-friendly UI (User interface) design, but granulation feeds most directly into the aural world of Rainpiece.

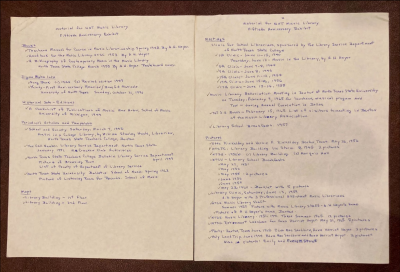

Figure 3. Work in progress maxpat view.

Aesthetic Decisions

Beyond the practical elements of score and patcher, there is the ultimate question of why. Why explore these subjects in particular? What do I hope to achieve in my thesis? As stated previously, Rainpiece serves as an exploration of the sound world created by various types of water; the specific types include rain, rivers, and springs, with the hope to achieve synthesis between the pre-recorded sound recordings and live instruments. As such, a few concepts have been invaluable to my research. One such notable concept is the ‘Soundscape’ as described by R/ Murray Schafer in his work Our sonic environment and the Soundscape: The tuning of the world. From the Interlude chapter, Murray Schafer notes that “throughout the history of soundmaking, music and the environment have bequeathed numerous effects to one another, and the modern era provides striking examples” (Schafer, 1994, pp. 112). It is clear that synthesizing acoustic instruments and interactive sound is not inherently new, nor are successful results. However, creating a unique soundscape that the audience can both recognize, and see the subjects in a new light, is the goal that I wish to achieve. Thus, using the concept of cross-timbral sounds is key to achieving this goal.

As for the second aspect, where the connections between the original sound and the resulting piece are concerned and the source bonding might be severed, Schafer notes that context is what builds our soundscape, “But when [sounds] are removed from their contexts… they may quickly lose their identities” (Schafer, 1994, pp. 150). While at first this may seem antithetical to the goal of my work, I would instead approach it as another opportunity: with the connections to a sound’s origin weaker, there is room for suggestion. Thus, an audience might be more willing to suspend their disbelief and allow for a heightened experience as the instrumental sounds mingle, contrast, or heighten the original water source sounds.

Narrative is a third aspect of the work I must consider. Throughout my studies with Dr. May, I have learned and discussed with him the implications of a linear structure, and the ways in which I may free the performers of my piece to create their own narrative decisions. Many of these narrative choices will likely come from archetypal narratives of storms and river flows. This will guide the listener’s ear and help them understand what to pay attention to. Ultimately, the sounds created by manipulations of my original water recordings and the sounds created by the live instruments should meld together and create their own world: one that is recognizable, yet invites exploration. It will allow myself, the composer, and the performers the opportunity to create a compelling narrative, and bring the audience a unique experience.

Conclusion

This semester, and indeed the duration of my thesis work thus far, I have explored and studied the acoustic, psychoacoustic, and narrative implication of water and the interactions my field recordings may have with the selected trio of live instruments. To serve these artistic goals, I will continue exploring the timbral relationships between the natural world and the ensemble, as well as learn about granulation, additional forms of sound manipulation, and the ensemble’s interaction with the computer.

References

Brown, E. (1965). Available forms. Assoc. Music Publ.

May, A. (2005). Wandering through the same dream.

Riley, T. (1964). In C. Associated Music Publishers Inc.

Schafer, R. M. (1994). Our sonic environment and the soundscape: The tuning of our world. Inner Traditions International, Limited.