A new structure, the Science and Technology Building, is being built on the corner of Mulberry and Avenue C. This is just a recent example of UNT’s focus on the sciences on the UNT campus. Forty-one years earlier another structure was built on Mulberry Street, this one on the corner of Avenue B. The Science Research Building opened in 1985, with 60,000 square feet spread over two floors. The architect was Preston Geren of Fort Worth.

The block where the building would sit was originally the site of single-family houses. Over the years the homes were replaced by small businesses and parking lots. At least one house was moved, by Littrell House Moving, to make room for the new science building.

Talks to build a structure for science research started under President Vandiver. However, the Coordinating Board was not willing to approve the building in 1980 because they felt the university was overbuilt. In 1981, the Board of Regents proposed a 60,000 square foot building. The Coordinating Board approved a 30,000 square foot building. Bruce Street, Board of Regents member, stated, “I am disappointed in the board’s decision, but I think their approval for a 30,000 square foot building was an important recognition on their part of the importance in updating NT’s research facilities.” [North Texas Daily, 1981-07-16]. The vice president of academic affairs, Howard Smith, referred to the Coordinating Board’s action as a preliminary approval. Dr. Smith said that the university planned to resubmit the request for the larger structure with an architect’s plan.

The Texas Legislature approved the construction of the larger Science Research Building in 1982. However, Governor Bill Clements asked that projects with legislative approval also had to receive Coordinating Board approval to proceed. UNT joined other colleges and universities in an appeal of the Clements’ rule. Waiting for the Texas attorney general to rule postponed the university’s request for construction bids.

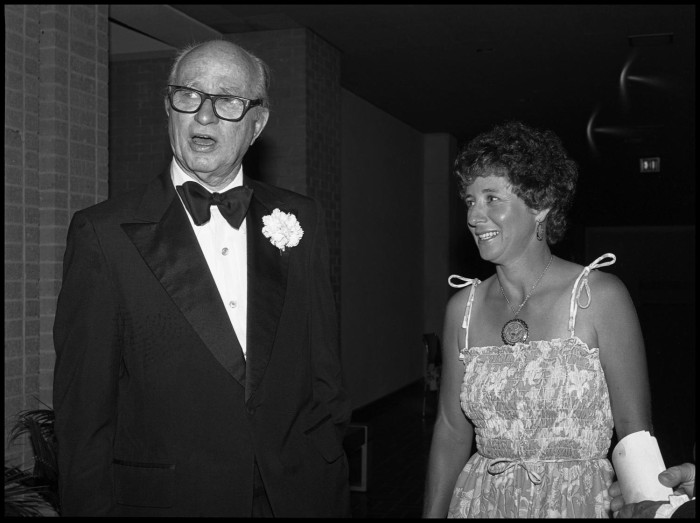

Despite the difficulties getting the project approved, it finally got underway. The Science Research Building, one of four projects the university undertook in 1982, started before President Hurley’ s inauguration. The Great Southwest Construction Company was building the structure. The groundbreaking for the Science Research Building was held in the Administration Building (now the Hurley Administration Building) due to freezing weather. Two large dirt filled containers were placed in the building. President Hurley and members of the Board of Regents dug earth from those canisters.

The new building was planned to hold offices and laboratories for chemistry, physics, and biology departments and the Institute of Applied Sciences. The primary use of the space was for laboratories, each of which was equipped with an emergency shower and safety exhaust hoods. The exterior of the building was finished with large panels of bricks which were bolted on. Each panel had 96 bricks held together with steel rods and concrete.

The construction was not without controversy. Two workmen were fired from the project due to yelling, whistling, and harassing behavior toward women who walked past the construction site.

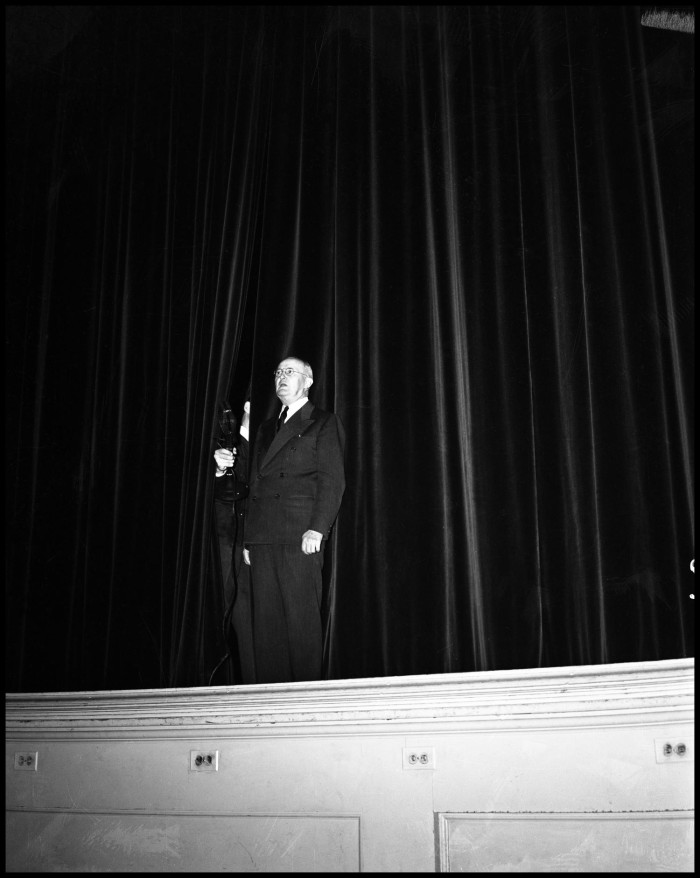

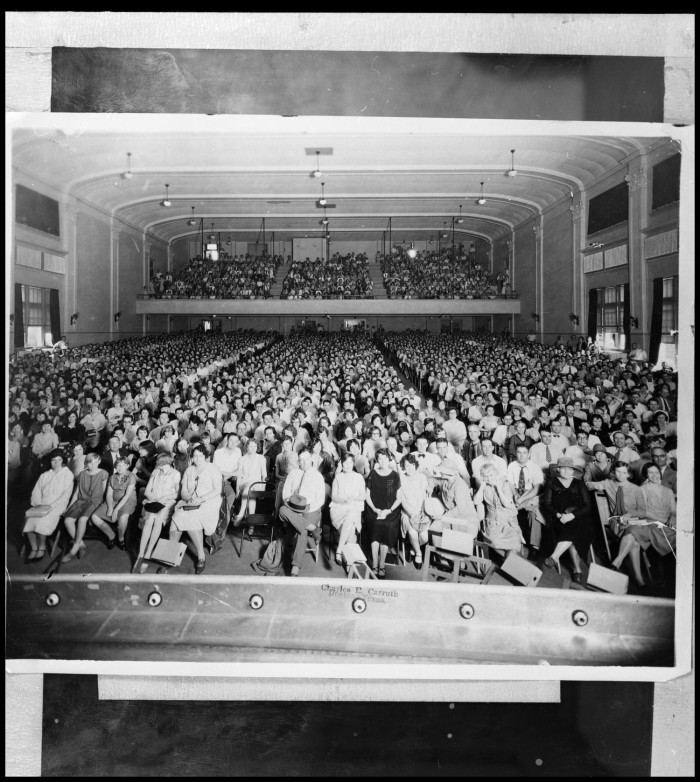

By July 1984, the bulk of the construction was completed. The remaining work on the structure was on the interior and the grounds. The estimated finish date was the fall of 1984. Departments finished moving into the building in May 1985. The official opening took place in October 1985 with Lieutenant Governor Bill Hobby as the featured speaker. “Our economic strength and health depend critically on the support of great institutions of higher education. In Texas, we have become dependent on oil revenues to support many of the things we want to do. For various reasons, oil revenues will become less dominant as time goes on, and we must find appropriate substitutes.” Lt. Gov. Bill Hobby [North Texas Daily, 1985-10-23]

By 1995, Dr. Nora Bell, dean of the College of Arts and Sciences, stated that the Science Research Building “is full and bursting at the seams….” The structure has been targeted for renovations over the years. Renovations took place on the second floor which included mechanical, electrical, and plumbing upgrades. The second floor was also altered to provide open space laboratories similar to those on the first floor. In 2011 renovations of $12 million were used to expand the structure. The work reflected the increase of science faculty who in turn needed more science labs. Renovations also took place during 2015-2017. This work focused on the laboratory space on the first floor. The exterior was also replaced due to deterioration. The building was given a new brick finish as well as façade changes.

The campus will continue to develop to provide growth opportunities for the sciences. Research was enhanced by the construction of the Science Research Building. The experiences with this structure will inform the expansion of science faculty and structures on campus.

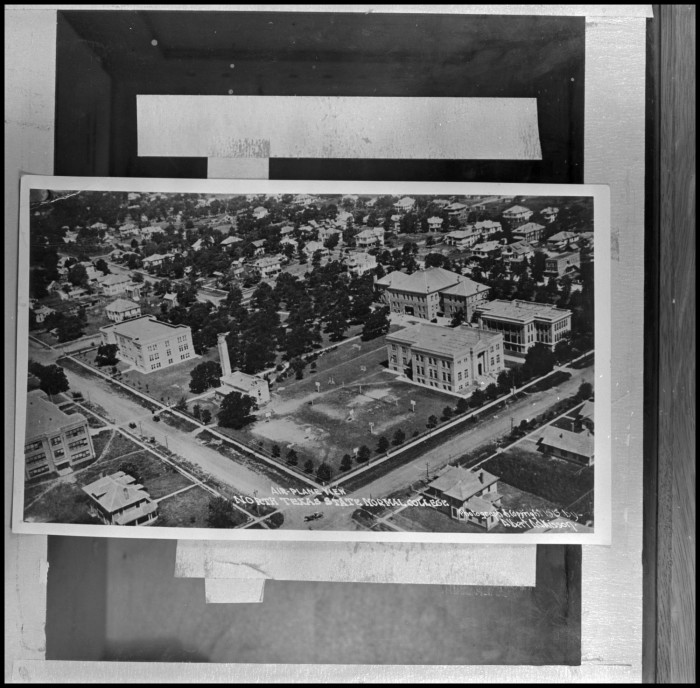

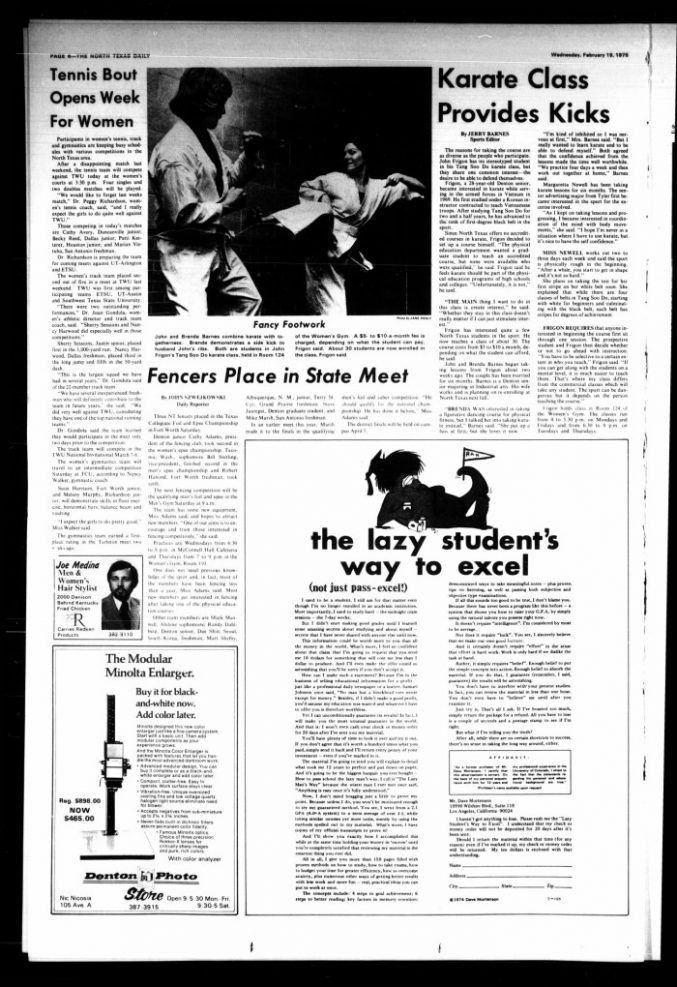

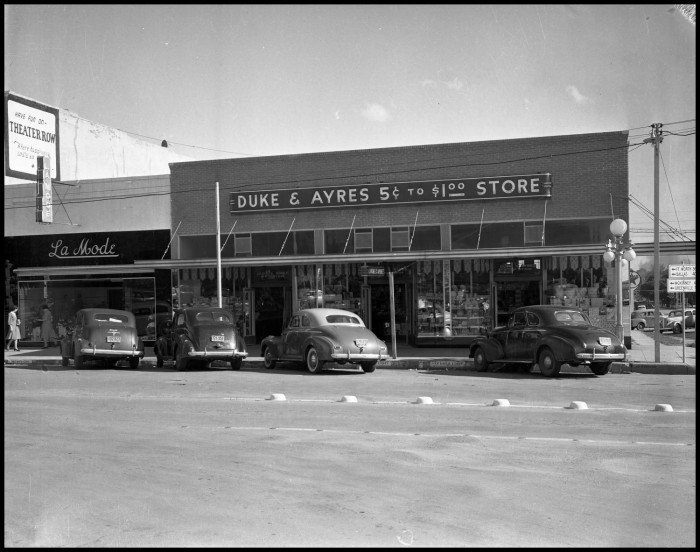

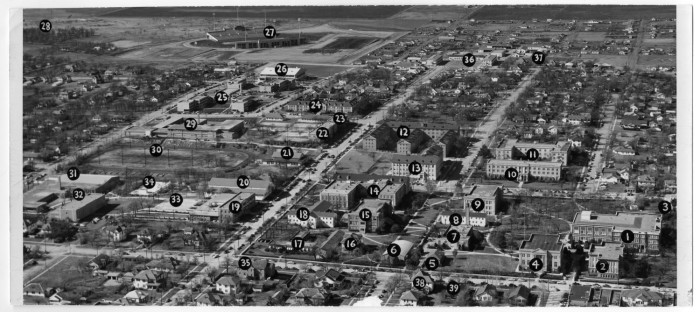

The campus in the 1940s shows the Auditorium Building in the lower left. To the right of that building is the President’s House and across Avenue B is the block that would eventually house the Science Research Building.

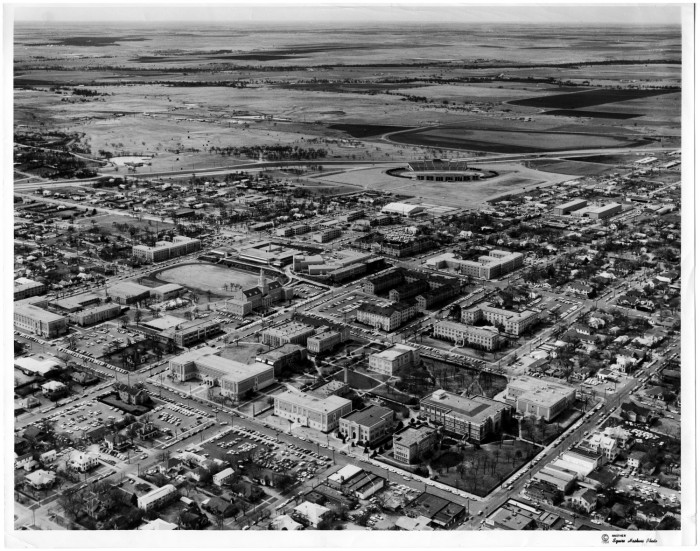

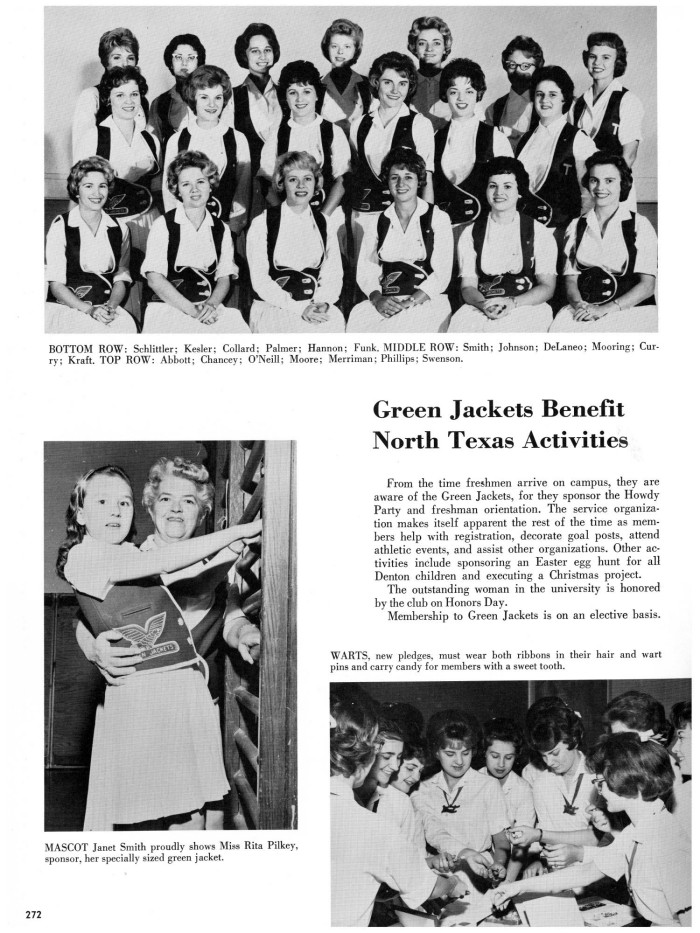

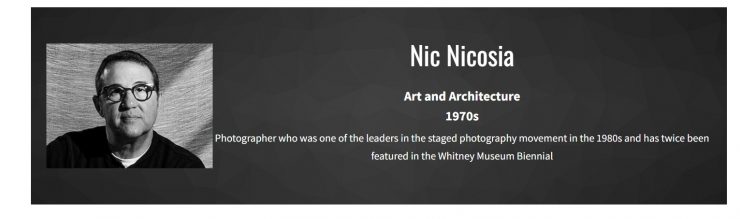

This shows the campus at the time of the construction of the General Academic Building in 1977. It shows the block where the Science Research Building and the Chemistry Building would eventually be located. Originally, this block was covered with single family houses. At the time this image was taken, the houses had given way to small businesses and parking lots.

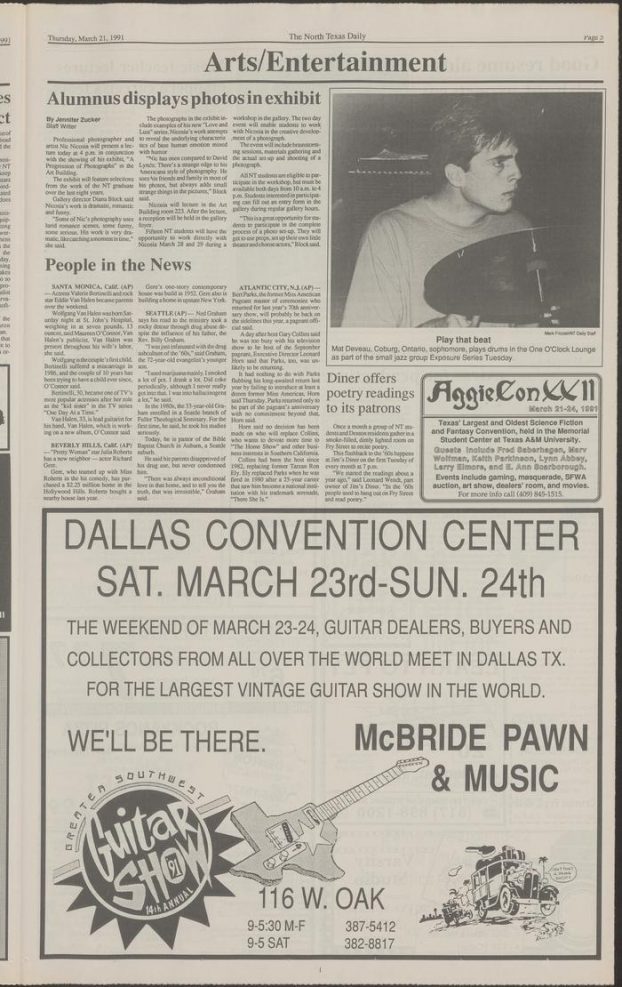

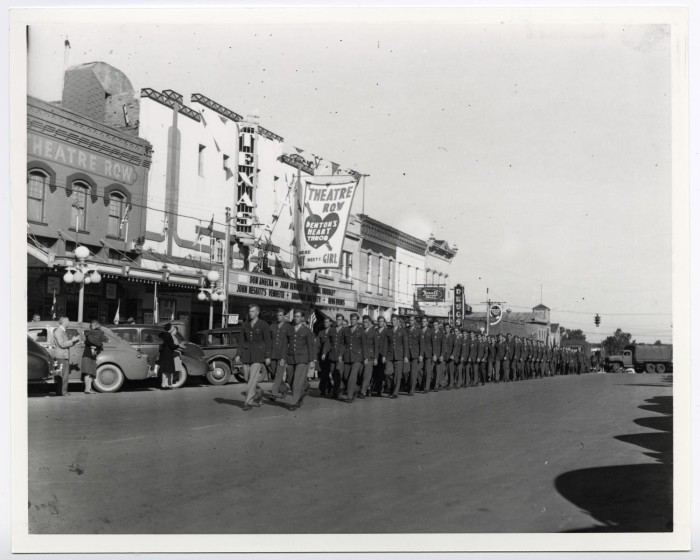

A campus aerial image that starts at the Performing Arts and Art Building and then looks west. The Science Research Building is on the right – to the right of the GAB.