The Eagle Park and recreation grounds area on the North Texas campus occupied land on what was formerly Scoular Hall (originally the Journalism Building), Stovall Hall, the Willis Library, and a number of other structures. The recreation area extended beyond what was replaced with the Laboratory School (now known as the Music Annex) to the west and stretched out to the east even before the current Administration Building was constructed.

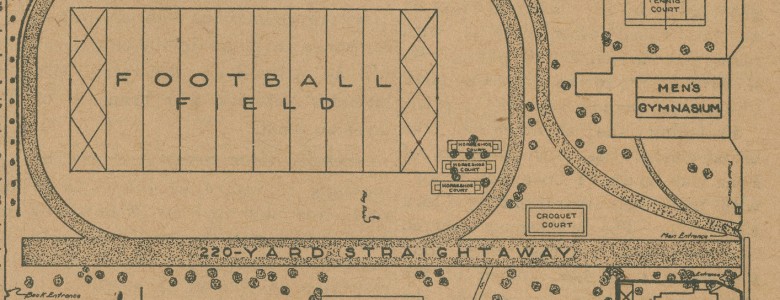

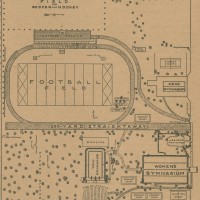

Eagle Park was a recreation area where croquet, volleyball, tennis, horseshoe and other activities could be enjoyed. It included a football field, a practice field for soccer and hockey, tennis courts, a men’s and women’s gymnasium, basketball courts, volleyball courts, an outdoor stadium, horseshoe courts, a shaded playground with trees, and, to the east, an archery area. It also included buildings such as the Men’s Gymnasium and the Women’s Gymnasium. A bowling alley was located behind the swimming pool to the west.

Originally, benches were part of the area where students could gather around the bandstand and watch theatrical performances, listen to music or, with the addition of a projection booth, watch films. The bandstand was an open air theater designed by architect O’Neil Ford. The stage of the bandstand was active throughout the 1920s and up until the late 1940s, when the Journalism Building took its place.

A swimming pool was part of the area behind the benches of the open air theater. When classes were not in session, the pool was open to the public, as were many of the areas on the grounds. The outdoor swimming pool was one of the last remaining structures of the recreation area, lasting even up through the 1980s and the early years of the Willis Library.

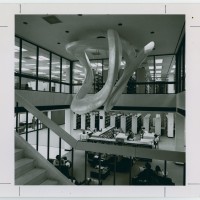

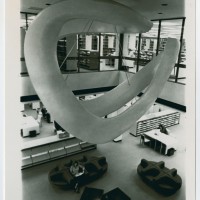

For many years, up until 1969, the current location of the Willis Library was occupied by the Willis Library. In photographs dating back to this year, early construction of the A.M. Willis, Jr. Library is visible in aerial views. Prior to this, this patch of land was the largest of the remaining pieces of Eagle Park.

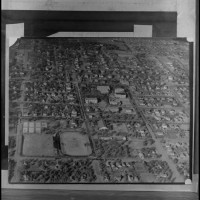

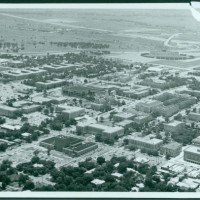

Gradually, through time, every piece of the Eagle Park area has disappeared. Aerial photographs illustrate a progression of the land’s development up to the present day. None of the land or structures that were once an integral part of the North Texas community do not exist anymore except in memory. If it were not for photographs and aerials, clippings, yearbooks, old maps and documents, no one would even realize the space now occupied by the Administration Building, the Willis Library, Music buildings, University Union, and the recently demolished Scoular Hall and Stovall Hall had such a rich history of activity and recreation throughout the 1920s and up through the 1960s.

— by S. Ivie, Associate Processing Archivist

- UNTA_U0458-100-864-02 Photograph of students playing on the tennis courts, 1942. In the image there are four tennis matches being played along a low sloping hill. A building takes up the far side of the courts.

- UNTA_U0458-098-708-03 Photograph of students acting in the play “Little Nell” at North Texas State Teachers’ College, 1942. Students in different costumes can be seen on the bandstand stage, perhaps in a rehearsal.

- UNTA_U0458-096-524-02 Five women play croquet. One woman prepares to hit the ball, while the others watch, 1942.

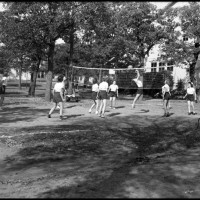

- UNTA_U0458-098-683-04 A group of women playing volleyball outside, 1942.

- UNTA_U0458-098-683-03 A group of men play volleyball in physical education class at North Texas State Teachers’ College, 1942.

- UNTA_U0458-096-525-01 Women play intramural volleyball on the Eagle Park court, 1942.

- UNTA_U0458-096-521-04 Men and women play croquet outside in an Eagle Park field, circa 1940-1949.

- UNTA_U0458-098-685-04 Photograph of four women holding bows and arrows in a physical education class at North Texas State Teachers’ College archery field, 1942.

- UNTA_U0458-094-335-02 a A football game on the Eagle Park field, circa 1950s.

- UNTA_U0458-100-851-02 The outdoor swimming with the open air theater in the background, circa 1940s. In the image the pool is filled with people doing different activities and some people are standing in the shade watching. Multiple rows or seats lead up to a stage and large screen for outside entertainment. Beyond the large area covered with trees you can see the courthouse at the top of the frame. The pool was in operation from the 1920s to 1986.

- UNTA_U0458-092-237-03 Women play croquet on the North Texas campus, circa 1940s.

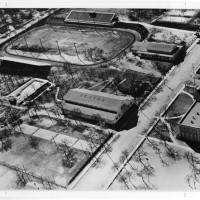

- UNTA_U0458-092-167-02 Aerial photograph of the football field, lab school, and quads, taken from the administration building, looking southwest.

- UNTA_U0458-092-162-01 Campus from an aerial perspective, July 29, 1949.

- UNTA_U0458-104-313-01 An aerial view of North Texas State Teachers College and Eagle Park, taken from above between 1920-1929. A group of fields are visible at the bottom left of the image, and the Administration building and Library, currently the Auditorium and Curry Hall, are in the center of the image.

- UNTA_U0458-091-150-03 The North Texas grounds from an aerial perspective, 1942.

- UNTA_U0458-091-150-02 The North Texas campus grounds from an aerial perspective, 1942.

- UNTA_U0458-091-150-01 The North Texas campus grounds from an aerial perspective, 1942.

- Aerial photograph of the North Texas State College campus in 1953. Numbered buildings are: (1) Administration Building (later, Auditorium), (2) Science Building, (3) Presidents House, (4) Historical Building (later, Curry Hall), (5) Industrial Arts, (6) Metal Shop, (7) Power Plant, (8) Drawing Building, (9) Manual Arts Building, (10) Marquis Hall, (11) Terrill Hall, (12) Bruce Hall, (13) Masters Hall, (14) Library, (15) Business Administration Building, (16) Kendall Hall (first to be named for President Kendall), (17) Hospital, (18) Education Annex, (19) Union Building, (20) Harriss Gym, (21) Men’s Gym, (22) Music Hall, (23) Orchestra Hall, (24) Chilton Hall, (25) Quadrangle, (26) Men’s Gym (new), (27) Fouts Field Stadium, (28) Golf Course and Club House, (29) Education Building (later Lab School), (30) Old Athletic Field, (31) Women’s Gym, (32) Journalism Building (later, Scoular Hall), (33) Union Slab, (34) Swimming Pool, (35) Home Management House, (36) Service Center (later, Physical Plant, (37) Leggitt Hall, (38) Men’s Building, (39) Mary Arden Lodge.

- An aerial photograph of the North Texas State University campus, circa 1969. In the center the A.M. Willis Library is under construction. The new Speech and Drama building is in the foreground. Texas I-35 runs behind Fouts Field Stadium.

- An aerial photograph of the North Texas State Teachers College. The original football field is along Chestnut Street. The swimming pool is just east of the field.

- An aerial photograph of the North Texas campus, circa 1969. The Hurley Administration Building is visible in the center of the photograph. Directly behind the administration building, the construction site for Willis Library is visible. Bruce Hall, Crumley Hall, Kendall Hall, and other buildings are also visible.

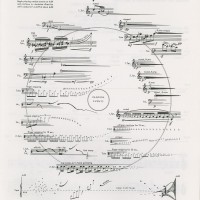

- A Campus Chat article about Eagle Park, July 23, 1932.

- Close-up of Eagle Park map from a July 23, 1932 Campus Chat article.