About this time most of us have probably already given up on maintaining our New Year’s resolutions. It might be worthwhile, therefore, to observe Benjamin Franklin’s birthday today by reviewing the “bold and arduous project” he devised for achieving moral perfection in his personal life, and considering how his system might be applied in defining our own values and achieving our own personal goals.

About this time most of us have probably already given up on maintaining our New Year’s resolutions. It might be worthwhile, therefore, to observe Benjamin Franklin’s birthday today by reviewing the “bold and arduous project” he devised for achieving moral perfection in his personal life, and considering how his system might be applied in defining our own values and achieving our own personal goals.

Establish Goals

The first stage in Franklin’s plan was to establish a list of moral principles he found himself in need of practicing. He coupled the name of each virtue with a definition in the form of a brief admonition, and arranged the list in a climactic sequence so that each virtue would be built on the achievement of the previous one.

This is the list he came up with:

- Temperance. Eat not to dullness; drink not to elevation.

- Silence. Speak not but what may benefit others or yourself; avoid trifling conversation.

- Order. Let all your things have their places; let each part of your business have its time.

- Resolution. Resolve to perform what you ought; perform without fail what you resolve.

- Frugality. Make no expense but to do good to others or yourself; i.e., waste nothing.

- Industry. Lose no time; be always employ’d in something useful; cut off all unnecessary actions.

- Sincerity. Use no hurtful deceit; think innocently and justly, and, if you speak, speak accordingly.

- Justice. Wrong none by doing injuries, or omitting the benefits that are your duty.

- Moderation. Avoid extremes; forbear resenting injuries so much as you think they deserve.

- Cleanliness. Tolerate no uncleanliness in body, cloaths, or habitation.

- Tranquillity. Be not disturbed at trifles, or at accidents common or unavoidable.

- Chastity. Rarely use venery but for health or offspring, never to dullness, weakness, or the injury of your own or another’s peace or reputation.

- Humility. Imitate Jesus and Socrates.

You might come up with a different list, depending on what is most important to you or which specific habits you need to practice. The defining admonitions also might be reworded or otherwise adapted to be more personally relevant and more contemporary.

Keep an Account of Progress

Franklin knew that trying to keep all these ideals in mind all the time would be an overwhelming and futile task, so he established a system for focusing on one habit every day for a week while noting any violations of the other principles, but not focusing on them. When he reached the end of a thirteen-week cycle, he would start over and repeat the entire program, completing four cycles every year.

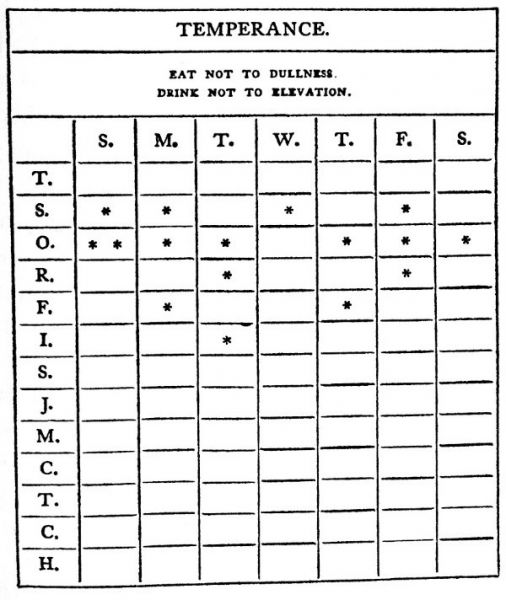

He designed an accounting ledger to keep a record of his progress, creating for each week a matrix that lists all the virtues in a series of rows, and the seven days of the week in a series of intersecting columns. He assigned one primary virtue to each week and gave himself a black demerit every time he found himself violating one of his principles, the object being to keep the entire row clean for the week’s featured habit, but keeping himself mindful what is happening in the other areas:

Franklin reused these pages many times and discovered that the constant marking and erasing wore them out quickly. Later he used a memo book with ivory pages that could be repeatedly erased without damage. If he were alive today, he would most likely be using an electronic spreadsheet or an iPhone app.

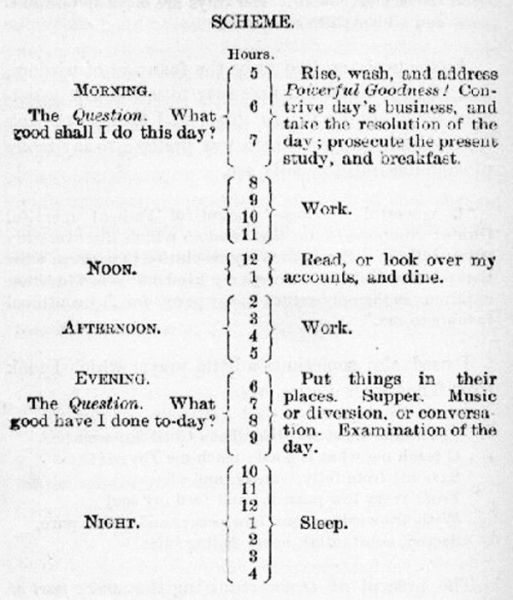

He also established a daily routine of working, resting, eating, and other activities, beginning each day by asking himself, “What good shall I do this day?” and ending each with the self-query, “What good have I done today?”

Evaluate Results

Franklin conceived this self-improvement program when he was twenty years old and kept it up off and on at least until he was seventy-nine, when he wrote about it in his memoirs. Did it work?

According to Franklin’s memoirs, his bold goal was to arrive at “moral perfection.”

I wished to live without committing any fault at any time; I would conquer all that either natural inclination, custom, or company might lead me into.

He certainly never arrived at moral perfection. His propensity for indulgence in food and drink, for example, and the ensuing gout from which he suffered because of it, are well-known.

His attempt at maintaining a constant state of mindfulness did lead to a self-awareness and an improvement in his behavior, however much he fell short of perfection, and he attributed much of his success to the regular application of this discipline:

To temperance he ascribes his long-continued health, and what is still left to him of a good constitution. To industry and frugality, the early easiness of his circumstances and acquisition of his fortune, with all that knowledge that enabled him to be a useful citizen and obtained for him some degree of reputation among the learned. To sincerity and justice, the confidence of his country, and the honourable employs it conferred upon him: and to the joint influence of the whole mass of the virtues, even in the imperfect state he was able to acquire them, all that evenness of temper and that cheerfulness in conversation which makes his company still sought for, and agreeable even to his young acquaintance: I hope, therefore, that some of my descendants may follow the example and reap the benefit.

Did you make any resolutions this year? If you’ve had difficulty maintaining them, or have any areas in your life you need to improve, you might want to try out Franklin’s system. Let us know if it works for you!

Article by Bobby Griffith.

Portrait of the young Benjamin Franklin by Robert Feke, c. 1748. Harvard University Portrait Collection.