Posted March 28th, 2022 by Justin & filed under Research Help.

Written by Omika Mishra

Searching for relevant databases for your field of research can be difficult but once you reach those databases, your research can be a breeze. A library database is a searchable electronic index of credible resources that have been published. Access to a multitude of relevant research resources from academic publications, newspapers, and periodicals is available through databases. E-books, pertinent Web resources, and diverse multimedia are all included in certain databases. The UNT library alone has access to close to 600 databases.

Why use library database?

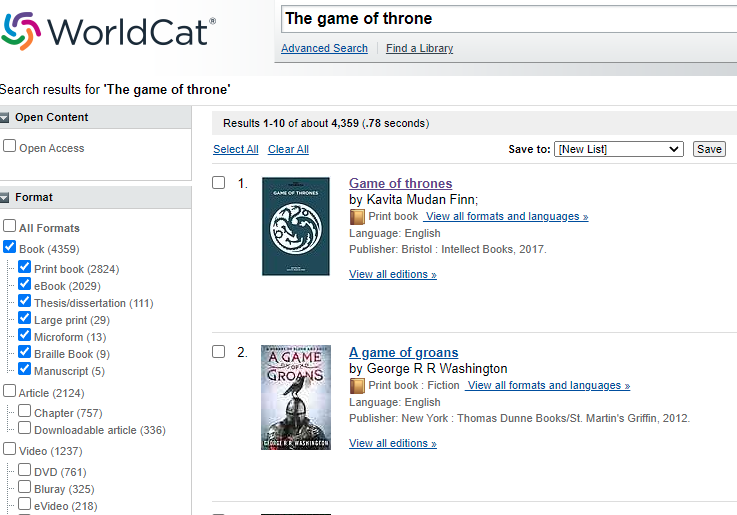

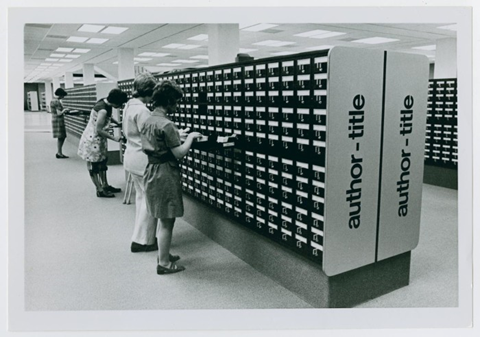

Information in a database has been tagged with various types of data, allowing for far more effective and efficient searching. You can search by author, title, keyword, topic, publication date, source type (magazine, newspaper, etc.), and many other criteria. Database information has been examined in some way, ranging from a rigorous peer-review publishing procedure to a popular magazine editor deciding whether or not to publish an item. Databases must be purchased, and the majority of the material is not freely available on the internet. As new information becomes available, the databases are updated on a regular basis. Database provides Information about citations. It includes the data you’ll need to correctly cite your sources and compile your bibliography. This information may or may not be included in the information you obtain via Google.

Here are a few steps on how to find databases using the UNT Library homepage:

- Visit the website https://library.unt.edu/.

- Once on UNT library home page, locate the blue box with options including “Search it all”, “Online articles”, “Books & more” and many more.

- Proceed to type in database name in “search it all” or go to “Database” to find more options.

- There are two search box “Find a Database” provides a list of databases present in the library and in the second box “Browse subject” will present a list of subjects to choose from like Accounting, Advertising and many more.

- Here at the top, you can type in the name of the database you are looking for and in the second blank space you search for databases based on subject such as “Public Administration”

- Once a selection is made, the website will populate information like the number of databases, name of databases, subject librarian related to this subject. Subject Librarian supports student in research on a specific subject.

You will find fields like:

“All subject” this is where you search for all the databases based on the subjects you choose like “Public Administration”.

“All Database Type” Here you will find what kind of databases are available like Bibliography, data set, E-books, E-journals, newspaper, Online video and many more.

“All Vendors/Provider” Here you will find list of providers like EBSCO, Thomas Reuters – Financial, Cornell Library and many more.

References (APA format):

UNT Library. University Libraries. https://library.unt.edu/

CQ Press. (n.d.). http://library.cqpress.com/index.php

Berkeley College. (n.d.). https://chat.library.berkeleycollege.edu/faq/89790

Introduction to Library Research. https://libguides.regiscollege.edu/researchintro/whydatabase. (n.d.).