Written by: Zoë (Abbie) Teel

Academic libraries have been a target of the national book ban crisis. There has been a proliferation of books that have been subjected to censorship in the last few years, especially books that deal with imperative topics such as gender identity, race, abortion, and sexuality. Books authored by individuals who are BIPOC (black, Indigenous, and people of color) are heavily under attack and face unfair, unjust scrutiny. Particularly, in the state of Texas, school libraries have faced many challenges regarding the works within their institutions: “Texas banned more books from school libraries this past year than any other state in the nation, targeting titles centering on race, racism, abortion, and LGBTQ representation and issues, according to a new analysis by PEN America, a nonprofit organization advocating for free speech” (Lopez, 2022).

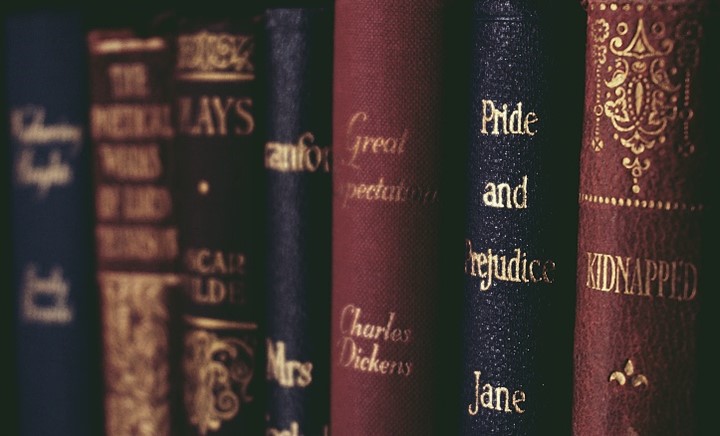

So, what is the big deal? Students are losing access to literature that grapples with topics they may be struggling with in their own lives. Having a piece of literature that allows students to explore and navigate the thoughts, feelings, and emotions they are experiencing, through characters and authors, gives them comfort and a safe space. Libraries are supposed to be the home of information; a place that demolishes barriers and welcomes knowledge. Academic libraries are the embodiment of intellectual freedom. Questioning why things are the way they are is at the heart of education.

Books face removal because they are considered potentially dangerous by individuals who feel a misguided sense of moral obligation, as we have seen especially here in Texas. However, lawmakers seem to disagree. “[Rep. Matt] Krause, a member of the hardline conservative Texas House Freedom Caucus who is also running for state attorney general, included in his inquiry a roughly 850-book list that included novels about racism and sexuality and asked the districts to identify which of those books were available on school campuses” (Pollock, 2021). It is important to note, that many of the lawmakers who are trying to restrict access to books, and moreover, restrict freedom of thought, have never worked with the education system or academia.

The American Library Association released the “Top 10 Most Challenged Books of 2021.” These ten titles “are only a snapshot of book challenges,” meaning that these are only a handful of the works that the Office for Intellectual Freedom have deemed “the most challenged.” (ALA, 2021). According to the ALA (2021), these titles included:

- Gender Queer by Maia Jobabe

- Lawn Boy by Jonathan Evison

- All Boys Aren’t Blue by George M. Johnson

- Out of Darkness by Ashley Hope Pere

- The Hate U Give by Angie Thomas

- The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian by Sherman Alexie

- Me and Earl and the Dying Girl by Jesse Andrews

- The Bluest Eye by Toni Morrison

- This Book is Gay by Juno Dawson

- Beyond Magenta by Susan Kuklin

UNT Libraries has made it a priority to not shy away from titles that are challenged. Having each of these ten titles in the catalog demonstrates that academic libraries, like UNT, are making a stand for books. By having these books in UNT Libraries’ collections allows the precedent to be set that student’s rights are important, and censorship does not belong in the library space.

The University of North Texas celebrates the freedom to read. Each year, the American Library Association holds “Banned Book Week,” which UNT Libraries has participated in hosting. UNT Libraries has a Banned Book Guide, which explores what Banned Book Week is and its history. It also offers trivia and videos about the most challenged books and why they are challenged.

Conclusively, it is obvious that representation matters. Representation that is found within the stories of books promotes learning, inclusivity, and growth. Consider checking out a banned, or censored, book from UNT Libraries.

References

American Library Association. (2013). Top 10 Most Challenged Books Lists. Advocacy, Legislation & Issues. https://www.ala.org/advocacy/bbooks/frequentlychallengedbooks/top10

Lopez, B. (2022). Texas has banned more books than any other state. The Texas Tribune; The Texas Tribune. https://www.texastribune.org/2022/09/19/texas-book-bans/

Pollock, C. (2021). Greg Abbott tells state agencies to block books with “overly sexual” content.The Texas Tribune; The Texas Tribune. https://www.texastribune.org/2021/11/08/greg-abbott-books-schools-texas/#:~:text=Gov.,other%20includes%20depictions%20of%20sex.