Looking for more information or have questions? Contact us at AskUs.

Perhaps the most striking difference for me and the hardest to overcome is the new realness I feel for the digital divide. The divide was something of an abstract concept to me before the pandemic. I had an awareness of the impact of income inequality on education from my experiences working with low income and rural students at UNT and other academic libraries. But that knowledge seems vague and cloudy compared to the piercingly clear picture I have now.Anima

Those who relied on the library to bridge the divide were certainly there but safely in my peripheral. Their basic needs were met with our library services and materials, so I only really “saw” them as the faces of those I helped each day and the numbers in our annual reports. Now, they have my full attention as we all struggle to face the awful truth that we could not keep them from being swallowed by the divide. It is unsettling for me to be in a position where I can no longer help everyone. My only hope is that we use this new awareness of the digital divide to remake our libraries into centers of learning that are truly accessible for all students.

Adapting to a new lifestyle, working remotely, and taking full-time online classes has been a challenge. To remain focused, motivated, and stay home. Here are some tips that I am trying my best to follow:SarahLastly, a motto: “You can still make something beautiful and something powerful out of a really bad situation.” by Gabe Grunewald.

- To eat right and stay healthy, which has helped me to stay focused and make the college experience more productive.

- Know what my resources are and develop an appropriate plan.

- Develop new hobbies such as gardening, sketching, cooking, and still looking for more.

I live in a tiny studio apartment, so as I’m sure you can imagine, suddenly having to spend all my work, school, and leisure time at home has been a challenge. One thing I was already doing before which has become even more important in the past few weeks is to set aside different spaces for different activities. I try to always eat in my kitchen area, work and study at my desk, etc. This makes it easier to follow a routine, focus on my work when I need to, and fully relax during my free time. Creating that separation also helps to make the small space feel bigger, which is much-needed right now.Frances

I’ve slowly adapted to this new lifestyle of doing everything at home by trying to create a sense of normalcy through the routine. This mainly involves sticking to healthy habits such as cleaning my space regularly and cooking full meals. Mentally, reminding myself that I still have school and work responsibilities and that I’m lucky to be able to stay home pushes me to take care of myself. When being at home all day inevitably gets boring, I look for excitement in activities such as exploring new recipes or doing puzzles. Even simple tasks like rearranging my desk or bookshelf can be an adventure. In times of uncertainty, I often feel like I’ve lost track of time, but I find comfort and reality in these routine tasks and new hobbies.Utsav

I am the kind of person who prefers staying home even during breaks but having to stay home for classes and work has been a challenge. This may be because the choice of actually going outside has been stripped away as it is rather unsafe. It has been challenging to focus on studies and work from home, where I usually just de-stress and play videogames. To remain productive and keep a sense of normalcy while staying home all day, I follow a routine to ensure both study and work time are well managed. Things that have helped me during this situation are talking to my mom on the phone and having her walk me through her recipes while I miserably fail to recreate her dishes, learning to play guitar and of course, playing videogames!Hui-Yu

Here are my personal tips to effectively study or work from home during the COVID-19 crisis. First, have a dedicated workspace in the home to help avoid distractions. Even if you live in a small apartment, it can be a corner of a living room or bedroom. Second, create a to-do list and prioritize tasks to remain focused and help with procrastination. In addition, taking short breaks is a great way to refresh yourself during the long work/study day. I usually use my break time to do a house chore. It is a good way to help myself reduce stress. At the end of the day, I video call my family back home and cook for the next day. Last and the most importantly, keep your spirits up!Madison

The most challenging aspect of this change has been trying to balance working remotely, completing homework, and helping my toddler understand why mom has to work sometimes. This is what has helped me deal with the situation.

I personally find it helpful to know I am not alone in this, and I hope other parents in this situation will find me sharing my experience helpful as well.

- Communication- As someone who has never submitted an assignment late, it has been difficult to let my professors know that I need an extension. I have always worked to maintain a balance between my professional life and my parent life, so it has been difficult to now have my toddler yelling in the background of a Zoom meeting. I have pushed myself to communicate with my boss and professors about my situation and am fortunate that everyone is so understanding.

- Staying in the moment-Since work-life and home-life have collided, I have found myself more often thinking about my kid at work and thinking about work when I am with my kid. This leads to me feeling like I am not doing either right. To combat this, I am trying to stay in the moment and focus at the task at hand. Though difficult, this has helped me.

Black Laptop Computer by Breakingpic licensed under Pexels

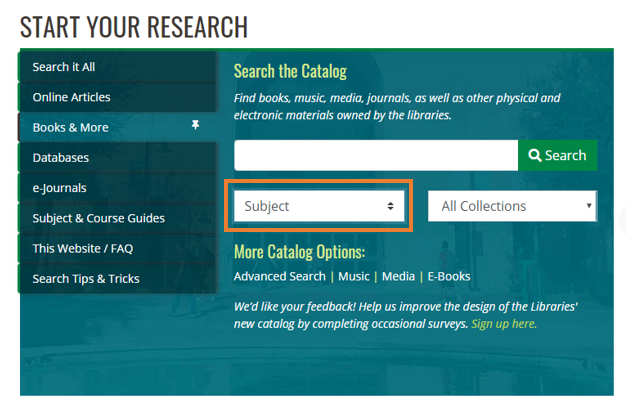

Screenshot from our library website by the author

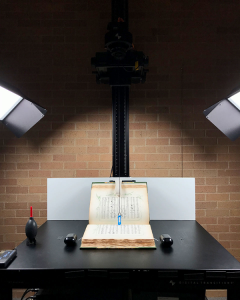

Willis Library provides many materials and services, which patrons and students may be surprised to learn exist. I am the GSA in the Digital Projects Unit of Willis Library, and I digitize primary materials for institutional partners to contribute to the Portal to Texas History. I have worked on projects like the CC Cox Collection, the National WASP WWII Museum Collection the Maude Kitchen Tintypes, and many more. I also digitize books, photographs and other objects for the UNT Digital Library! This kind of work requires much in terms of time, technology and know-how. As a graduate student in the College of Visual Art and Design (CVAD), I am on my way to earning an MFA in Photography. The Digital Projects Unit was in search for a GSA that had technical experience in photography, and began a relationship with the Photography Department in CVAD. As an MFA student in Photography, I originally set out to only focus on the artistic expression of making photographs. When I discovered an opportunity to work for the Digital Projects Unit here in Willis Library I jumped at the chance to work here. I have been here for the past two years, digitizing materials primarily using the Phase One system—a tethered capture camera system used by many institutions to digitize cultural heritage materials.

In digitization, we aim to preserve materials in a digital format so that the item, through proxy of the computer screen, will be available to a worldwide audience for the foreseeable future. “Digitization is the conversion of any type of original, be it paper, photographic prints or slides, three dimensional objects or moving images into a digital format.” (Astle & Muir, 2002. p. 67). This digital format can exist in a variety of formats that many of us with some computer proficiency may recognize, such as .TIFF and .JPEG. There is much information in Library Science scholarship which examines access and preservation goals that digitization can solve, as well as some of the challenges that can arise from this method of preserving cultural heritage. My main experience in this field has been through photography, using it as a tool to digitize cultural heritage materials.

Copy stand with Phase One/DT Photon system in the Digital Projects Unit. Photo by the author

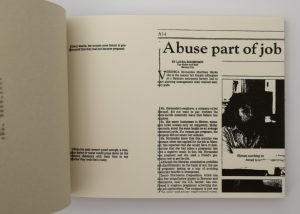

Video clip KXAS-TV screenshot, licensed under University of North Texas Libraries, The Portal to Texas History

There is an incredible amount of overlap for artists, like myself, who seek primary sources for research, and for the purpose of artmaking. Students in art can take advantage of what the Portal to Texas History and the UNT digital library have to offer. As an artist, there are many possibilities for using the Portal to Texas History for source materials such as news articles, photographs, and other primary sources. I have used video clips themselves from the Portal in my own work, as primary source research, as well as speaking to the ideas I want to communicate. This is an important aspect to creating research-based art today. Also, I have used other databases like the Newspaper Archive to create a stab bound book pertaining to my research. To take advantage of these databases that provide primary sources to make artwork is both relevant to history and the current day.

Artist Book Part 1. Photo by the author

Artist Book Part 2. Photo by the author

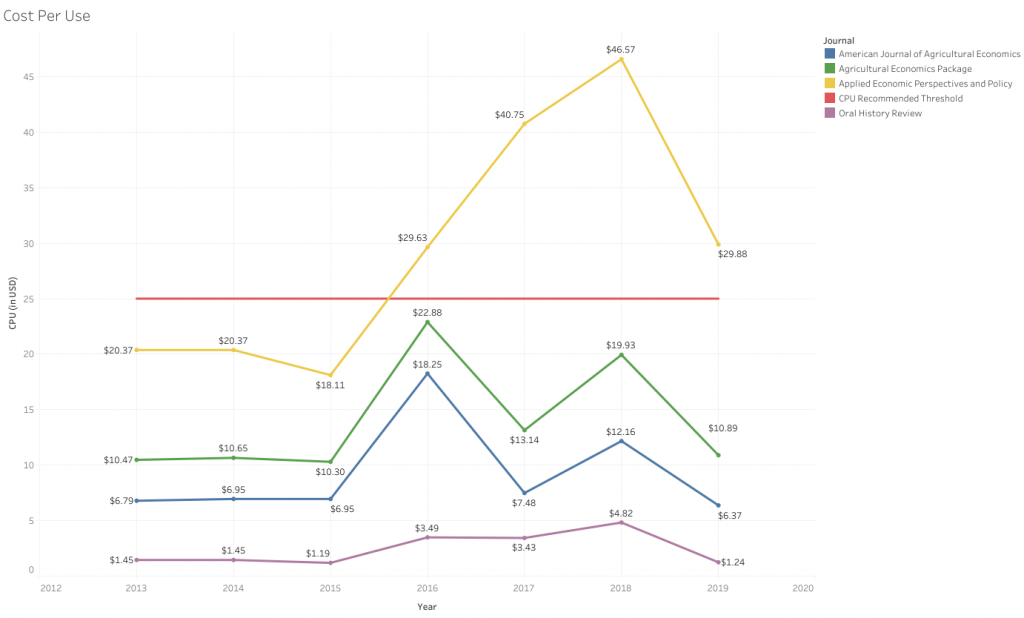

Oxford Specific Journal Use Analysis 2020 by the author licensed under University of North Texas Libraries Collection Assessment

Full Frame Shot of Shelf by Pixabay licensed under Pexels

Screenshot of subject term search from our library catalog

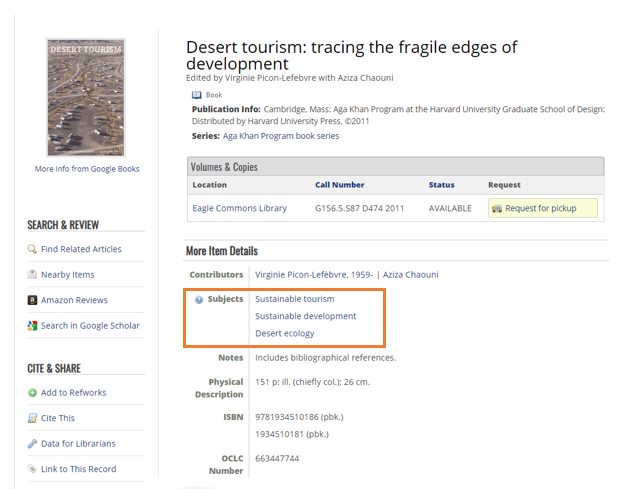

Screenshot of item record from our library catalog

Stacked Books by Suzy Hazelwood licensed under Pexels

Selling EBook by Mohamed Hassan licensed under pxhere

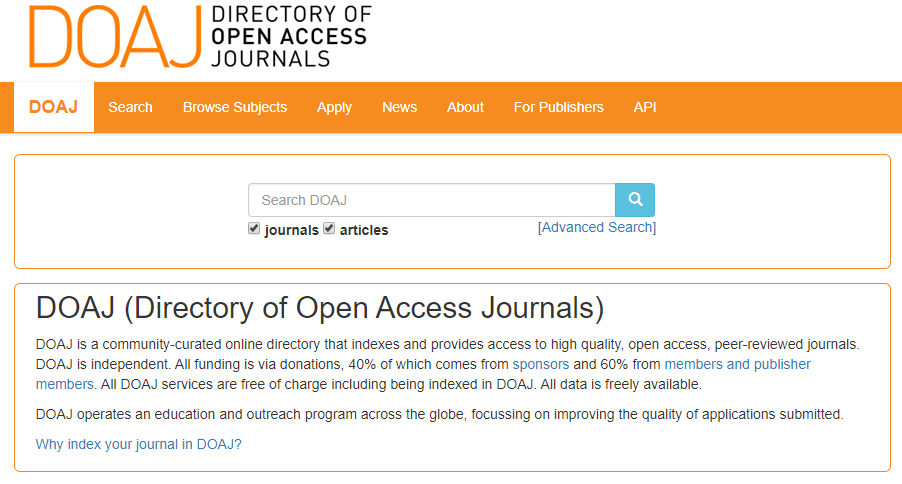

Screenshot of DOAJ homepage

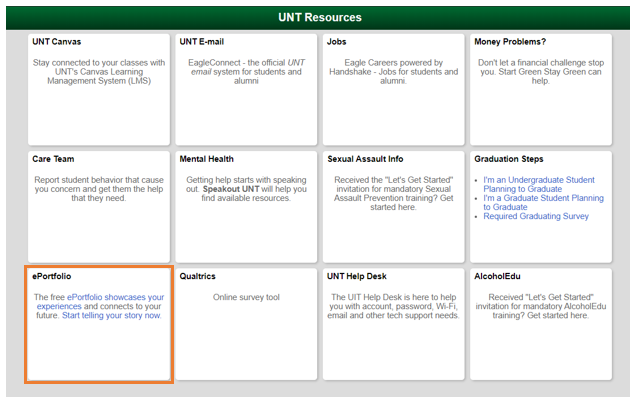

Screenshot of UNT resources from myUNT