Written by: Anima Bajracharya

Whether you are writing a thesis, dissertation, or research paper, it is crucial to access prior literature and research findings. Academic research databases make it easy to locate the literature you are looking for, and UNT Libraries is an excellent start for your research. UNT Libraries have great subscription-based databases and other online resources that are fully accessible to all current UNT students, faculty and staff members from virtually anywhere in the world. Subscription-based databases consist of published journals, reports, newspapers, magazines, documents, books, image collections, and many more. Libraries subscribe to and provide these resources for their patrons.

Due to the pandemic sticking around, many students, faculty, and staff members are trying to access electronic resources from off-campus for their research assignments. When working on your research off-campus you might encounter an article or other resources that are of your research interest, but when you try to access it, the resource is behind a paywall. If you are faculty, staff or a currently enrolled student, then you will be asked to log in using your EUID and EUID password to access most of the subscription-based electronic databases. But if you need many electronic resources from the UNT libraries databases for your research assignments, then UNT has various proxy access tools that may help access those materials from off-campus.

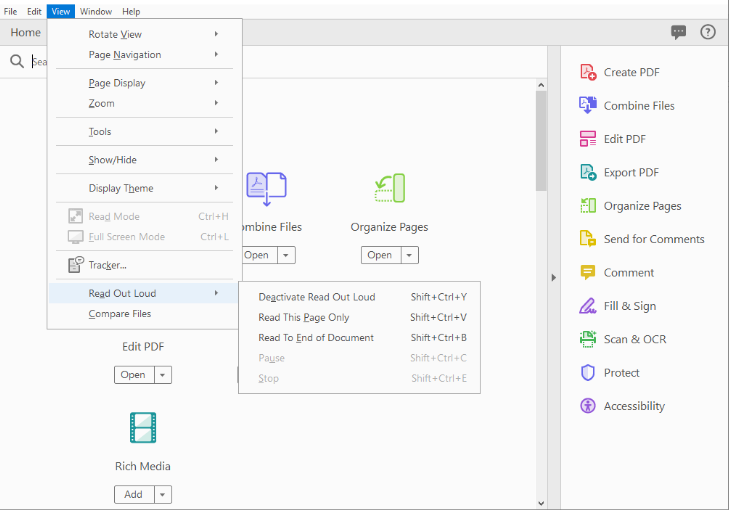

When I need to access electronic resources, one method that I find convenient is connecting through UNT’s Virtual Private Network (VPN). UNT’s VPN is very beneficial and reliable if you need to access electronic resources that are only available on the UNT Network. You can simply download and install the AnyConnect VPN client on your personal device and log in using your EUID and EUID password. You can find information on the installation of AnyConnect VPN: https://it.unt.edu/installing-vpn-client. It is easy to use, and once you are connected to VPN, you can access the library’s electronic resources just like you would using UNT library computers. Some other options for Proxy access tools that UNT provides are Bookmarklet, EZProxy redirect extension (Chrome), and link builder. You may find more information on these library proxy tools: https://library.unt.edu/proxy-tools/.

You may also find more information about on and off-campus access to Electronic Resources: https://library.unt.edu/services/on-off-campus-access/.

While accessing the electronic resources from off-campus, if you encounter any troubleshooting issues you can always contact Ask Us or leave a comment below.