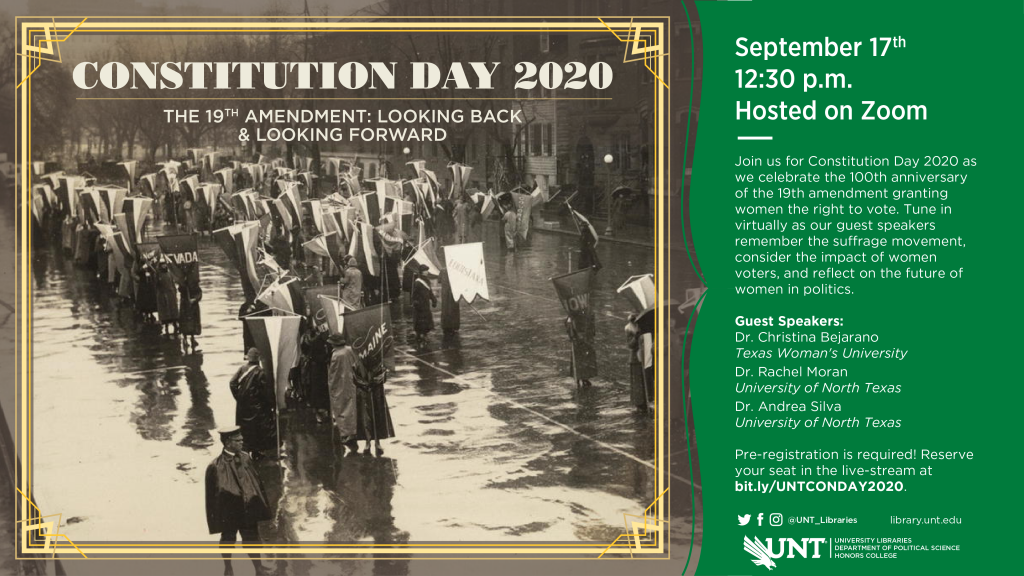

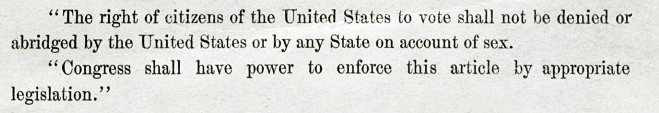

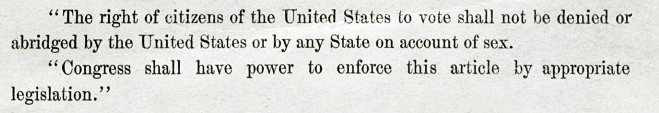

One hundred years ago today, at 8:00 a.m. on August 26, 1920, without fanfare, in the privacy of his own home and unseen by the press or the public, Secretary of State Bainbridge Colby formally certified Tennessee’s ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, bringing to a culmination a 72-year, non-violent campaign to acknowledge women’s right to vote.

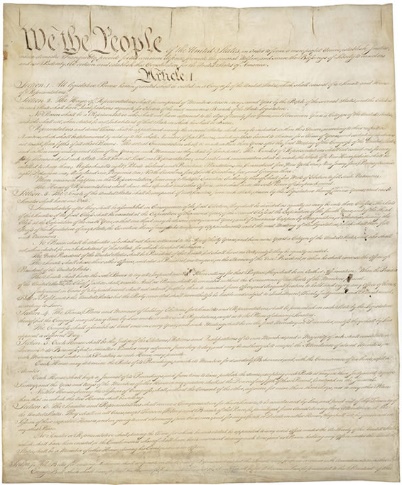

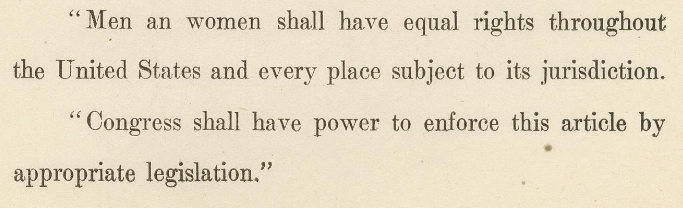

The language was simple:

Earlier Attempts at Woman Suffrage

Today it is difficult to comprehend a world where it’s considered perfectly normal for people to own other people, while the concept of women voting is considered the height of absurdity, but for decades even the staunchest advocates for women’s rights often disagreed on whether it was appropriate for women to demand the right to vote.

On March 31, 1776, as her husband John was in Philadelphia arguing the cause of American independence from Great Britain, Abigail Adams sent him the following forward-thinking suggestion:

…and by the way in the new Code of Laws which I suppose it will be necessary for you to make I desire you would Remember the Ladies, and be more generous and favourable to them than your ancestors.… If perticuliar care and attention is not paid to the Laidies we are determined to foment a Rebelion, and will not hold ourselves bound by any Laws in which we have no voice, or Representation.

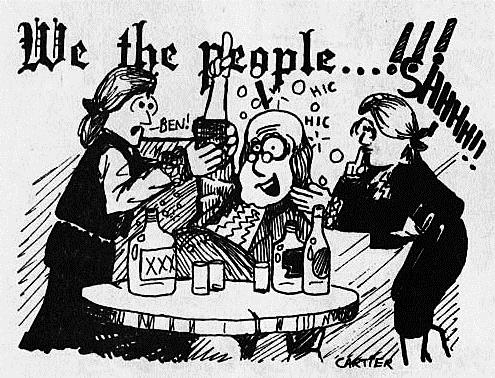

Although John Adams often depended on his wife’s wise counsel, this time his response was shortsighted and frivolous:

As to your extraordinary Code of Laws, I cannot but laugh.… Depend upon it, We know better than to repeal our Masculine systems. Altho they are in full Force, you know they are little more than Theory…, and in Practice you know We are the subjects. We have only the Name of Masters, and rather than give up this, which would compleatly subject Us to the Despotism of the Peticoat, I hope General Washington, and all our brave Heroes would fight.

American women continued to have no right to vote even after African-Americans were emancipated from slavery by the Thirteenth Amendment and guaranteed full citizenship and equal protection by the Fourteenth Amendment, which in 1868 introduced the word “male” into the Constitution—for the first time, and in connection with voting rights—arousing the ire of Susan B. Anthony, among others.

In 1869, Anthony and her long-time friend and collaborator Elizabeth Cady Stanton split from the American Equal Rights Association over support of the Fifteenth Amendment, which would prohibit denial of suffrage based on race, and co-founded the National Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA), which worked for women’s suffrage, divorce reform, and equal pay for women. Although they both supported universal suffrage, and Stanton had in fact included it in her Declaration of Sentiments introduced at the 1948 Seneca Falls Convention, which is often held to be the place where the women’s rights and women’s suffrage movements officially began in the United States, both opposed ratification of the Fifteenth Amendment because it failed to recognize women as citizens with voting rights.

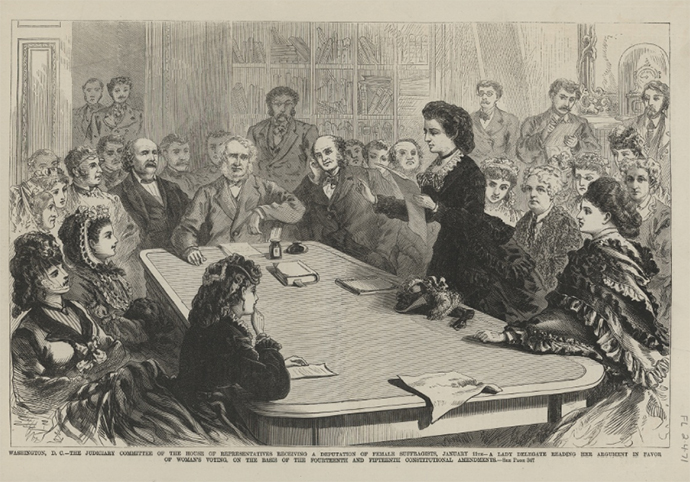

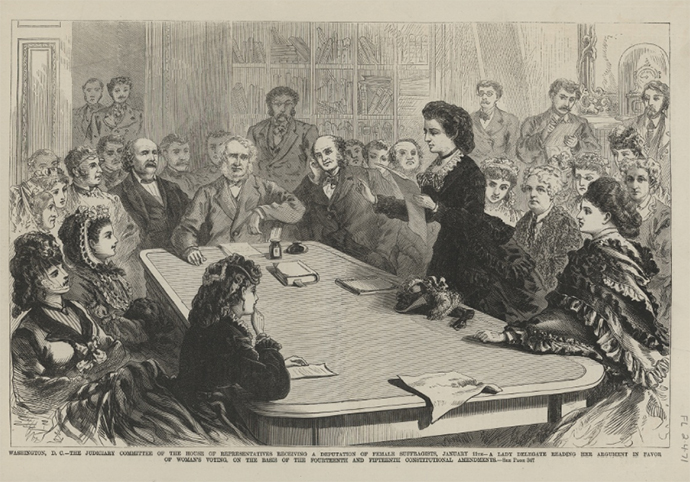

In 1871, the iconoclastic Victoria Woodhull became the first woman to address a congressional committee, arguing before the House Judiciary Committee that women already had the right to vote because that right was guaranteed to all citizens by the Fourteenth and Fifteenth amendments. The chairman objected, “Madam, you are no citizen—you are a woman!” and the committee tabled her request. Still, her speech attracted so many suffragists and reporters that, in one reporter’s words, “Washington became one grand conversational salon.”

In 1872, after ratification of the Fifteenth amendment, Anthony was arrested for voting illegally. She fought the charges unsuccessfully and was fined $100—a debt she refused to pay. Because the judge declined to sentence her to prison time, she lost her right to file an appeal, which would have allowed the suffrage movement to take the question of women’s voting rights to the Supreme Court.

From 1892 to 1900, Susan B. Anthony served as president of the National American Woman Suffrage Association (created by a merger of the NWSA with the competing American Woman Suffrage Association). In this role she canvassed the county giving speeches, gathering petition signatures, and lobbying Congress in support of women’s suffrage.

Sadly, neither Anthony nor Stanton saw the culmination of all their hard work, although they never lost faith that their vision would eventually come to pass. In 1902 the now elderly Susan B. made these remarks about the matter:

If I could live another century! I do so want to see the fruition of the work for women in the past century. There is so much yet to be done, I see so many things I would like to do and say, but I must leave it for the younger generation. We old fighters have prepared the way, and it is easier than it was fifty years ago when I first got into the harness. The young blood, fresh with enthusiasm and with all the enlightenment of the twentieth century, must carry on the work.

A New Generation

Carrie Chapman Catt was one of the members of that “younger generation.” A schoolteacher and newspaper editor, Catt took over leadership of the NWSA after Susan B. Anthony retired in 1900. Catt developed the NWSA’s “Winning Plan,” a conservative, incremental approach to women’s suffrage that focused on winning voting rights in at least 36 states, the number needed to ratify a federal amendment.

Alice Paul represented a more militant approach. After earning her master’s degree at the University of Pennsylvania, Paul had moved to London to continue her studies and there joined the Women’s Social and Political Union (WPSU), a militant British suffrage organization led by Emmeline Pankhurst and her daughter Christabel. From them Paul learned tactics and techniques of direct action such as organizing huge marches, staging extravagant, theatrical demonstrations, and using acts of disruption and civil disobedience to draw attention to her cause. This unbridled approach worked brilliantly at drawing attention to the movement, but it did not please the more conservative Catt, and the two leaders often clashed. Alice Paul and her co-suffragists also often clashed with the police.

On March 3, 1913—one day before Woodrow Wilson’s inauguration—the Women’s Suffrage Parade, organized by Alice Paul, took place in Washington, D.C. Inez Milholland—a suffragist, labor lawyer, and socialist who worked for prison reform, peace, and equality for African-Americans—led the parade wearing a white cape and seated on a white horse. Milholland campaigned unceasingly despite deteriorating health, and at the age of 30 collapsed in public uttering the words “Mr. President, how long must women wait for liberty?” then died in a hospital shortly thereafter. She was convinced that women’s unique traits qualified them to become “housecleaners for the nation” whose votes could help alleviate social evils such as crowded tenements, sweatshops, poverty, hunger, prostitution, and child mortality. Today many of these conditions still exist, as do voter suppression, unequal pay, and many other violations of the most basic human rights.

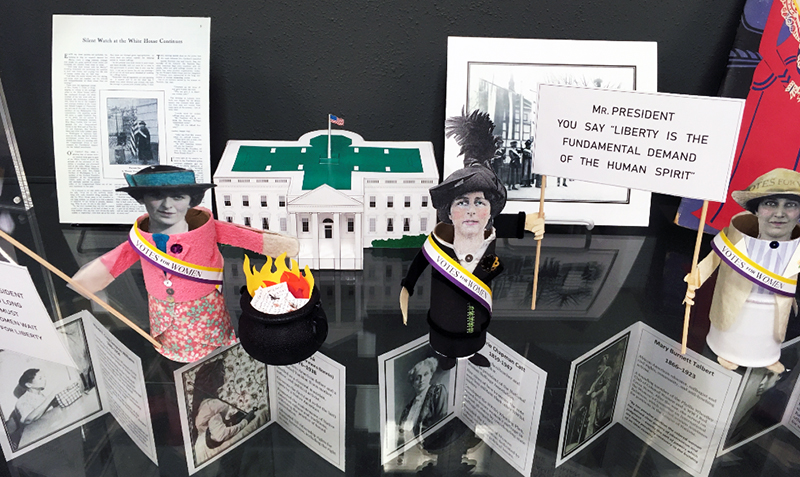

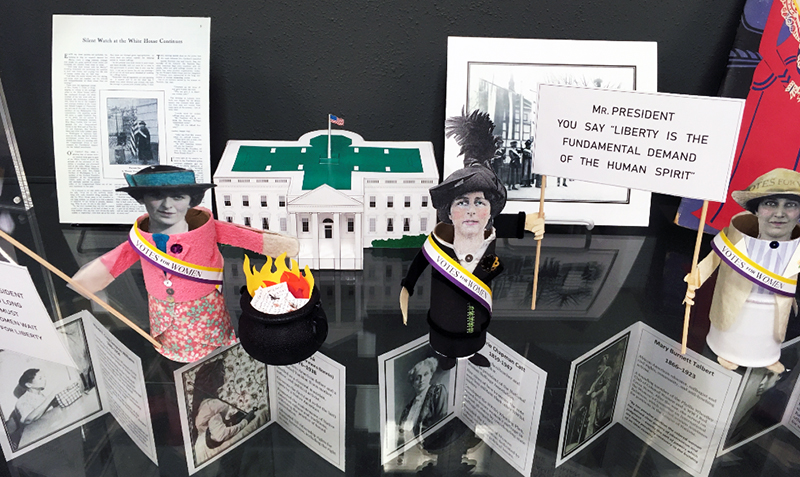

In January 1917 a group of women organized by Alice Paul became the first group to ever protest outside the White House. Known as the Silent Sentinels, they picketed several hours a day, six days a week, for almost two and a half years, never speaking a word, but silently urging President Wilson with their signs to support a suffrage amendment. Many of them were beaten, arrested, and jailed. They would continue their protests in jail by staging hunger strikes, which often resulted in more beatings and being force fed through a tube stuck up the nose. The resulting public outrage and outcry over their treatment is often credited with turning the tide toward support of women’s suffrage, and on June 4, 1919, Congress passed a joint resolution proposing a Nineteenth Amendment to the Constitution.

⠀

By the middle of 1920, 35 of the required 36 states had voted to ratify the amendment, four other states (Connecticut, Vermont, North Carolina and Florida) declined to put it to a vote, and all the other states except Tennessee had rejected it outright. The deciding vote therefore came down to the Tennessee state legislature, and that vote now stood at a tie, with a single vote remaining.

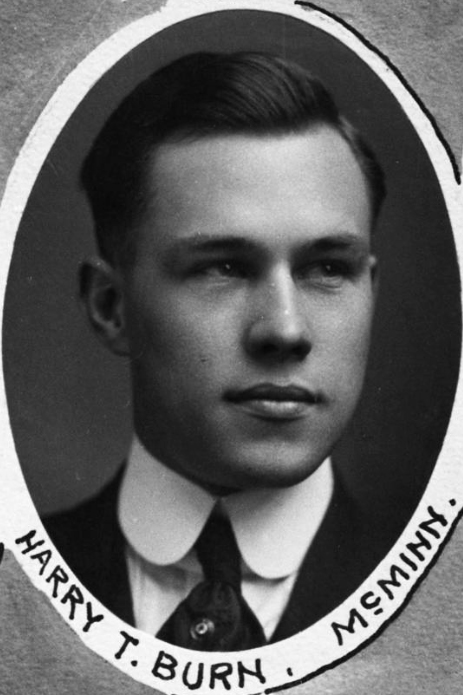

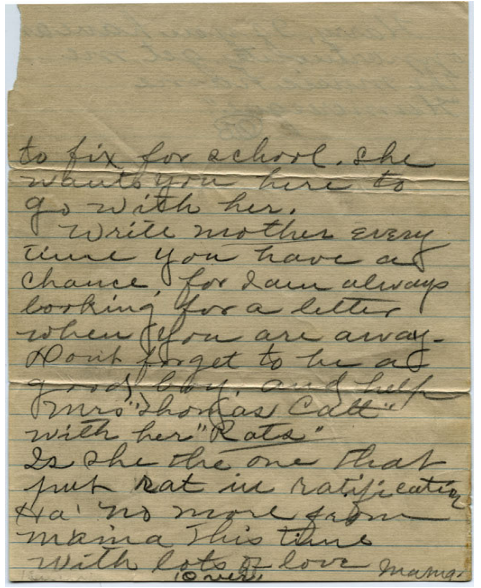

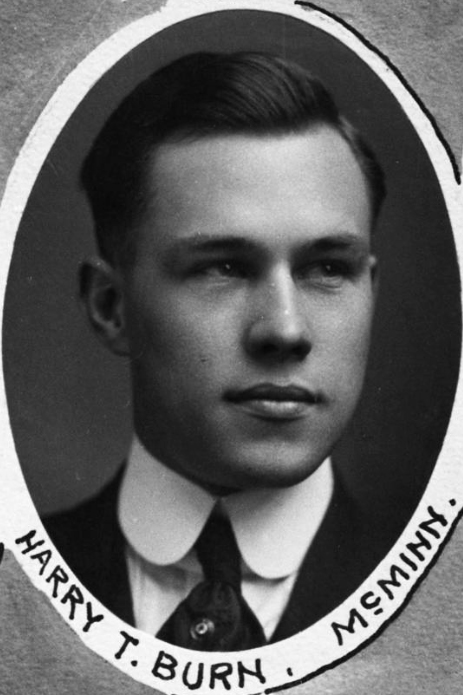

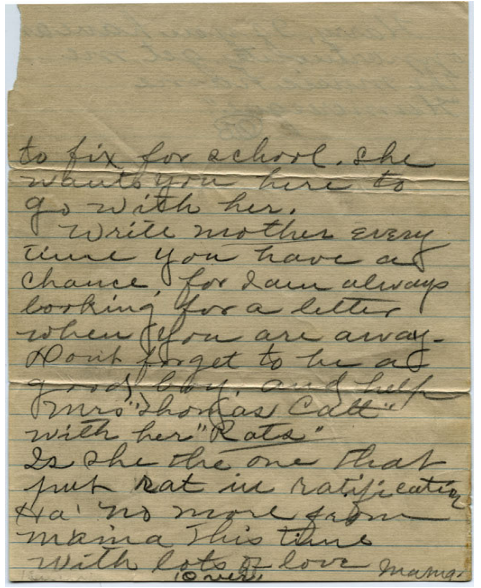

At the tender age of 24, Tennessee state representative Harry T. Burn from the McMinn County district suddenly found himself facing the responsibility of casting the deciding vote to ratify or reject the Nineteenth Amendment at the Tennessee General Assembly in 1920. The red rose on his lapel, as well as his past “nay” votes on the issue, confirmed his anti-suffragist position. He had already voted in favor of tabling the amendment, but that vote had also ended in a tie and did not carry. What the public did not see, however, as he stood up to declare his vote was a seven-page handwritten letter from his mother, Phoebe Ensminger Burn (known to her friends and family as “Febb”), urging him to “be a good boy” and “help Mrs. ‘Thomas Catt’ with her ‘Rats.’” (“Is she the one that put rat in ratification,” she further teased.) Along with the letter, Burn had hidden a yellow suffragist rose inside his jacket pocket. It was a history-making change of heart as Burn’s “aye” unexpectedly reverberated in the Senate chamber.

Fourteen years after Susan B. Anthony’s death, the act named after her was ratified as the Nineteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution. Though she did not live to see the results of her life’s work, Susan B. had played a crucial role in securing female suffrage at the national level.

On February 15, 1921 (Susan B. Anthony’s birthday), sculptor Adelaide Johnson’s monumental statue “The Women’s Movement” was unveiled in the Capitol Rotunda. The monument contains portraits of Susan B. Anthony, Lucretia Mott, and Elisabeth Cady Stanton, copied from busts the artist had sculpted earlier when the subjects were still alive. In this monument, they arise out of a block of rough-hewn Carrara marble—a symbol of the unfinished struggle for women’s rights—and a vague, abstract shape rises behind the three women to represent all the other women who might continue their fight.

In 1979, the U.S. Treasury minted the Susan B. Anthony dollar, making her the first female to be represented on U.S. currency.

Unfinished Business

Passage of the Nineteenth Amendment did not automatically secure the right to vote for all American women:

- Native American women were not considered U.S. citizens—except under certain special circumstances, such as being married to a white man—and therefore could not vote.

- African-Americans were prevented from voting by poll taxes, literacy tests, threats of violence, and other tools of voter suppression.

- Discriminatory immigration laws prevented many Chinese women (the Page Act) or Chinese men and women (the Chinese Exclusion Act) from becoming U.S. citizens, and in 1924 the Johnson-Reed Act excluded all Asians from immigrating to the U.S.

- The 1907 Expatriation Act declared that female U.S. citizens who married non-citizens were no longer Americans.

Pioneers such as Mabel Ping-Hua Lee and Zitkala-Ša helped pave the way for many of these women to win the right to vote years—sometimes decades—after the Nineteenth Amendment was passed, and some still fight today against felony disenfranchisement laws, voter I.D. laws, and other laws that continue to discriminate against women and minorities.

On Valentine’s Day 1920, six months before the Nineteenth Amendment was ratified, Carrie Chapman Catt founded the League of Women Voters, a non-partisan, non-sectarian organization aimed at educating voters on political issues.

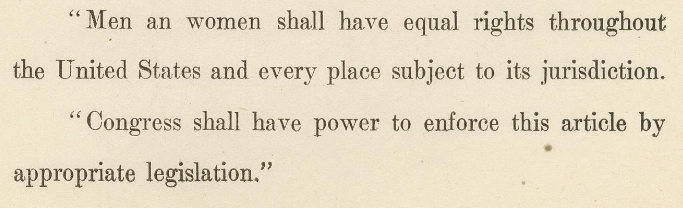

After helping to secure women’s suffrage, Alice Paul penned the Equal Rights Amendment (ERA) with Crystal Eastman in 1923. While middle-class women were largely supportive of this amendment, working-class women pointed out that passage could result in losing certain protections regarding working conditions and hours of employment. Like the Nineteenth Amendment, this one was short and succinct. (It was also misspelled.)

The ERA was reintroduced in the early 1970s, but as of 2020—nearly a century after it was introduced—it has not been ratified.

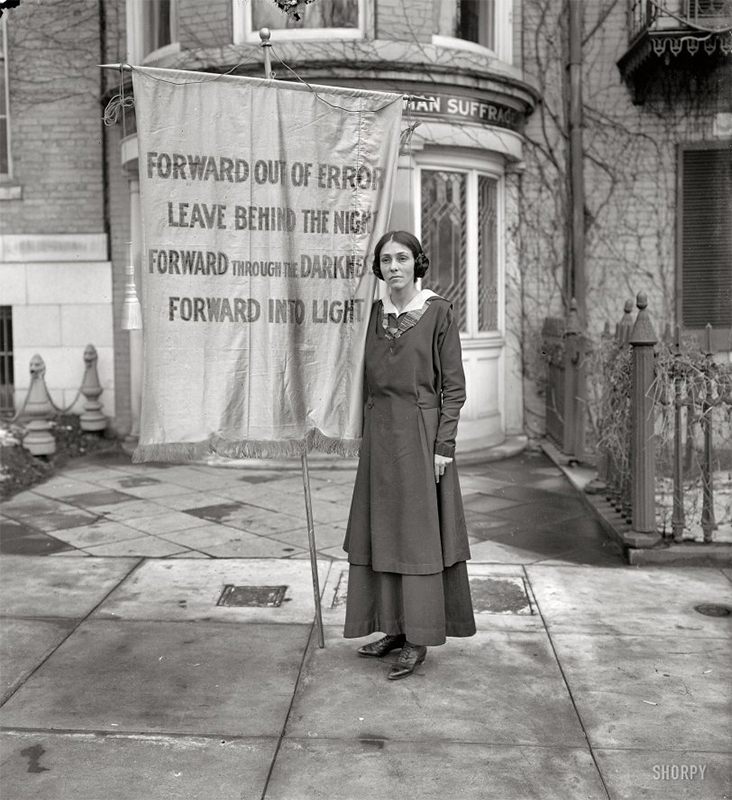

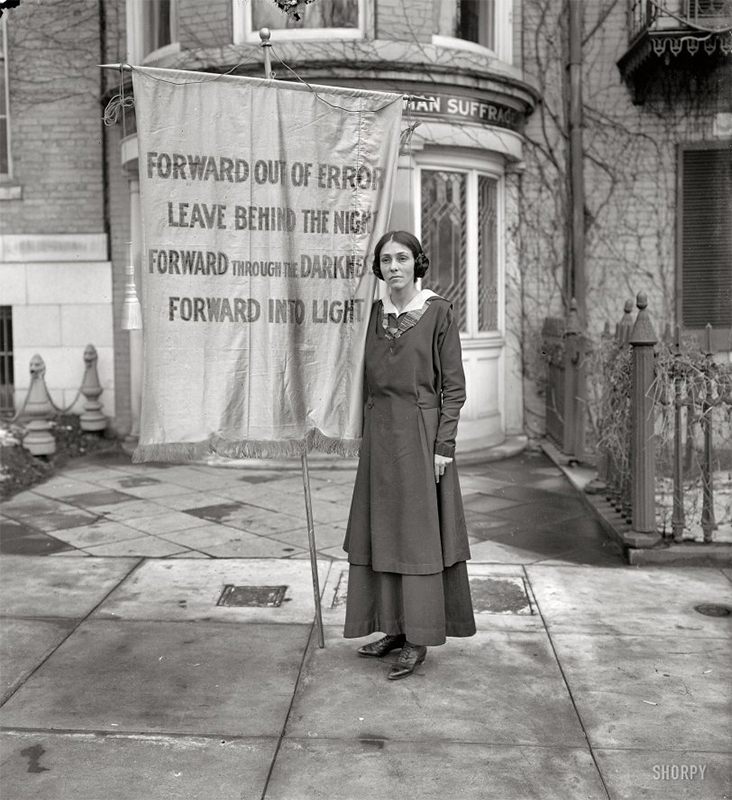

One hundred years after women won the right to vote, the battle for equality is still not over. We hope you have been inspired by this story and will consider how you can continue the fight for the rights of women and other oppressed people in your own neighborhood and throughout the world. What part will you play? As you join the fight for liberty, justice, and equality, let these words from Henry Alford’s hymn “Forward Be Our Watchword”—carried on a banner by Inez Milholland at her first suffrage parade, then later displayed during her memorial—serve as inspiration:

Forward, out of error,

Leave behind the night;

Forward through the darkness,

Forward into light!

Author: Bobby Griffith

Image credits:

Photo of Eagle Commons Library Woman Suffrage exhibit by Bobby Griffith.

Portrait of Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton, c.1880, from 19C American Women in a New Nation.

Photo of Victoria Woodhull courtesy of Collection of the U.S. House of Representatives.

Photo of Susan B. Anthony silver dollar from Heritage Auctions Lot 1449, 29 April 2010.

Photo of Carrie Chapman Catt courtesy of Library of Congress Manuscript Division, available under the digital ID mnwp.149004.

Photo of Alice Paul courtesy of Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division.

Photo of Silent Sentinels courtesy of Library of Congress American Memory Collection.

Photo of Inez Milholland courtesy of George Grantham Bain Collection, Libary of Congress, Reproduction Number: LC-DIG-ppmsc-00031.

Photo of Harry T. Burn courtesy of Tennessee Virtual Archive.

Photo of letter from Febb Burn courtesy of Calvin M. McClung Historical Collection, Knox County Public Library.

Portrait of Mabel Ping-Hua Lee from New-York Tribune, April 13, 1912. Reproduced in Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers, National Endowment for the Humanities and the Library of Congress.

Photo of Zitkala-Ša by Gertrude Käsebier, courtesy of the Smithsonian Institution.

Photo of woman holding banner in memory of Inez Milholland, uploaded from Shorpy.com, a photo-blog site specializing in vintage photography. Source url: 5414.