This Sunday, March 9, most of the population of the United States will perform the annual chore of setting their time-keeping devices forward by one hour, as we enter the seemingly ever-lengthening portion of the year referred to as Daylight Saving Time—surely an ironic term for the many students who will lose one precious hour of their Spring Break this year! (Usage note: don’t ever call it Daylight Savings Time, even if you’re a congressman.)

Historical Background

Benjamin Franklin is credited with first conceiving the idea for a daylight-saving law, which he proposed (perhaps as a joke) in an anonymous and humorously-worded letter to the editor published in the Journal de Paris in 1784.

The first serious proposals for such a law came from the entomologist/astronomer George V. Hudson in New Zealand in 1895 and 1898, and from the builder William Willett in England in 1907. (Willett, incidentally, was the great-great-grandfather of Chris Martin of Coldplay, the band responsible for the songs “Clocks” and “Daylight.”)

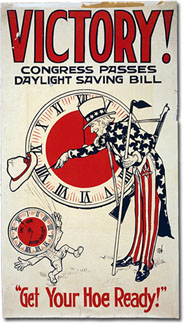

Franklin’s whimsical idea was not taken seriously in the United States until Congress passed the Standard Time Act of 1918 to economize on fuel during the First World War. By then, several European countries had already adopted some version of a daylight-saving law.

Franklin’s whimsical idea was not taken seriously in the United States until Congress passed the Standard Time Act of 1918 to economize on fuel during the First World War. By then, several European countries had already adopted some version of a daylight-saving law.

The law turned out to be quite unpopular in the U.S., especially among farmers, who found it unnatural and disruptive, and it was abolished immediately after the war. It was reinstated during the Second World War, then abolished again after that war, then reinstated inconsistently by various state and localities. It has been a continual source of controversy up to the present day. A 2007 Congressional Research Service Report for Congress summarizes the contentious history of this law over the decades.

Observance

The latest version of the law was implemented in 2007 as Section 110 of the Energy Policy Act of 2005. Under current law, Daylight Saving Time (DST) is observed in the United States from 2:00 a.m. on the second Sunday in March until 2:00 a.m. on the first Sunday in November, theoretically saving energy during the longer days and keeping children safe (and candy companies in business!) during the prime trick-or-treating hours of Halloween.

A few U.S. states and territories do not observe DST:

- Arizona (except for the Navaho Nation, which does observe DST)

- Hawaii

- American Samoa

- Puerto Rico

- The Virgin Islands

Controversies

Among the advantages that have been imputed to DST are that it saves electricity and the money spent on lighting during the evening hours; it offers more daylight hours for recreation after our jobs, studies, or chores and encourages people to spend more time exercising and socializing; it stimulates tourism and business; and it reduces crime and traffic accidents during the evening hours.

Opponents to DST have objected that changing the clocks twice a year is inconvenient, unnatural, and confusing; the extra cost of air-conditioning at night negates any savings in reduced lighting; the extra driving drives fuel-spending up and generates pollution; the extra hour of darkness in the morning leads to more traffic accidents and endangers children on their way to school; and the jolt to our inner circadian clocks is unhealthy.

Many of these assertions for and against have been based more on hunches than on proven facts, but there have been several studies of the effects of daylight-saving laws in various places around the world. A 1975 study by the U.S. Department of Transportation indicated that extending DST from a six-month period to an eight-month period might have modest benefits in the areas of energy conservation, traffic safety, and reduced violent crime, although their conclusions were not asserted with much confidence. A 2005 report by the U.S. Department of Energy indicated a small savings in electricity during the daylight saving period, while a study of daylight saving time in Indiana suggested that a reduced demand for lighting is negated by an increased demand in electricity for heating and cooling, especially in the southern states. Perhaps most disconcertingly, several studies have shown that there is a spike in the rate of heart attacks, and even a rise in the rate of suicides, following the spring time shift.

A recent telephone survey showed that the number of Americans who believe that the advantages of daylight saving time are worth the trade-offs may be dwindling, but a White House petition to have the law abolished expired before receiving enough votes to elicit a response. For now, it seems, the law—and the controversy—will continue.

Would You Like to Know More?

The National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) has answers to several frequently asked questions about Daylight Saving Time, as well as information about the current DST rules.

The National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) has answers to several frequently asked questions about Daylight Saving Time, as well as information about the current DST rules.

The U.S. Naval Observatory has compiled a chart showing the beginning and ending dates of Daylight Saving Time (which they call Daylight Time) from 2006 to several years from now.

For a list of government documents and other publications at the UNT Libraries related to daylight saving time, search the subject heading “daylight saving” in the Library Catalog. More titles can be found in the Library of Congress catalog.

Visit the Daylight Saving Time WebExhibit to learn more about the history of daylight saving time, about the reasons for it and the controversies surrounding it, and about how other countries around the world observe—or don’t observe—Daylight Saving Time, often referred to as Summer Time outside the United States.

Timeanddate.com also has a helpful compilation of information on their Daylight Saving Time—DST page, including tips on how to minimize the health risks encountered when we shift the clocks forward, and a chart summarizing how DST is observed around the world.

Article by Bobby Griffith.

Photos from Library of Congress: http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2002722591/ and http://www.loc.gov/pictures/resource/hec.13949/

Romances and Love Stories

Romances and Love Stories

The

The

On January 29, 2014, inspired by Andrew Jackson’s spirit of openness and by the fictional “tradition” portrayed on television, the Obama Administration is sponsoring the first

On January 29, 2014, inspired by Andrew Jackson’s spirit of openness and by the fictional “tradition” portrayed on television, the Obama Administration is sponsoring the first  Many of us take a day off from work or classes on the third Monday in January to honor the life and legacy of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. This day has been

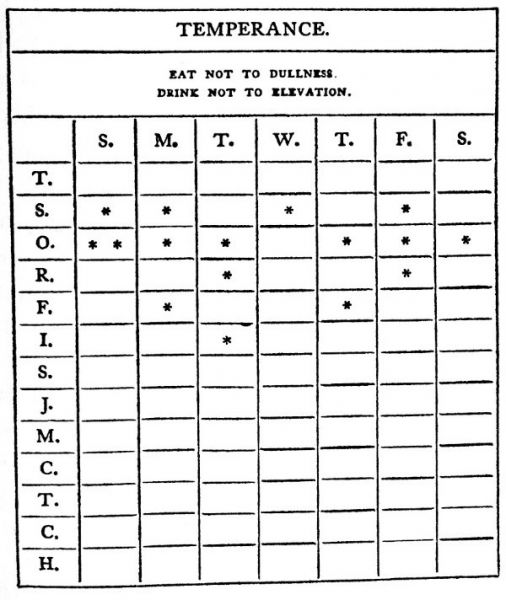

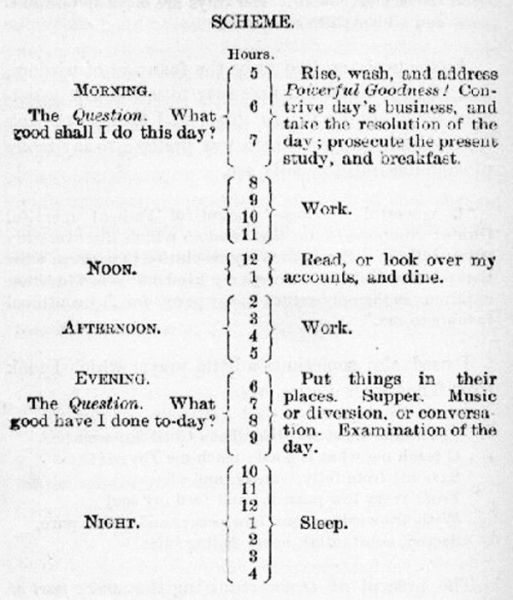

Many of us take a day off from work or classes on the third Monday in January to honor the life and legacy of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. This day has been  About this time most of us have probably already given up on maintaining our New Year’s resolutions. It might be worthwhile, therefore, to observe Benjamin Franklin’s birthday today by reviewing the “

About this time most of us have probably already given up on maintaining our New Year’s resolutions. It might be worthwhile, therefore, to observe Benjamin Franklin’s birthday today by reviewing the “

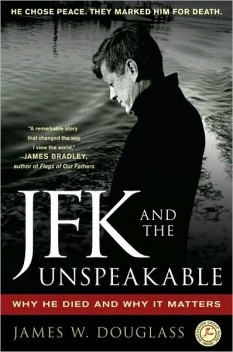

Fifty years ago today, at 12:30 p.m., President John F. Kennedy was shot and killed in Dallas, Texas. Two days later the chief suspect in his death,

Fifty years ago today, at 12:30 p.m., President John F. Kennedy was shot and killed in Dallas, Texas. Two days later the chief suspect in his death,  This book is largely based on evidence gathered while the author, who once successfully prosecuted Charles Manson, prepared for a

This book is largely based on evidence gathered while the author, who once successfully prosecuted Charles Manson, prepared for a  This book,

This book,