[Library Building of the North Texas State Teachers College, photograph, date unknown; University of North Texas Libraries, The Portal to Texas History; crediting Denton Public Library.

The Government Documents Collection at the University of North Texas Libraries is 75 years old this year.

In the words of James Madison, “A popular Government, without popular information, or the means of acquiring it, is but a Prologue to a Farce or a Tragedy; or, perhaps both. Knowledge will forever govern ignorance: And a people who mean to be their own Governors, must arm themselves with the power which knowledge gives.” (Letter to W. T. Barry, August 4, 1822).

Here is a brief history of how we became a federal depository library and how we have developed our collection and services over the years in an ongoing effort to provide our ever-burgeoning clientele with free public access to government information.

First Request Is Rejected

Our quest to become a depository library got off to a rocky start when our first request was rejected in 1937.

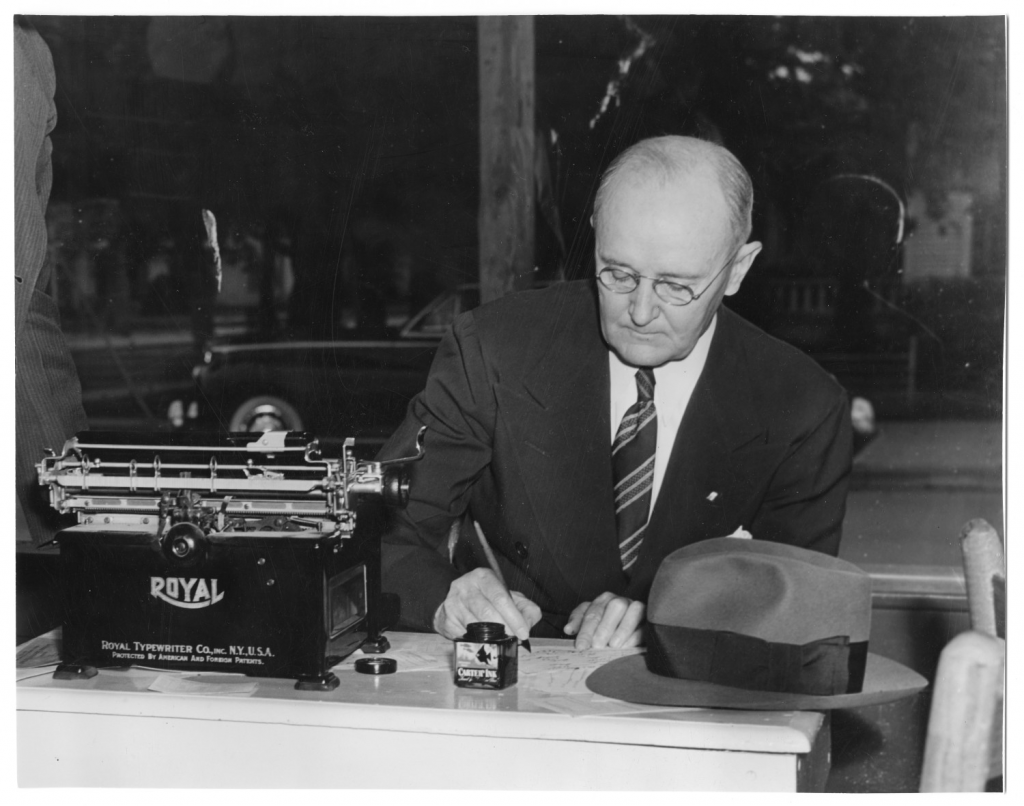

W. J. McConnell, photograph, c. 1935; University of North Texas Libraries, The Portal to Texas History; crediting Denton Public Library.

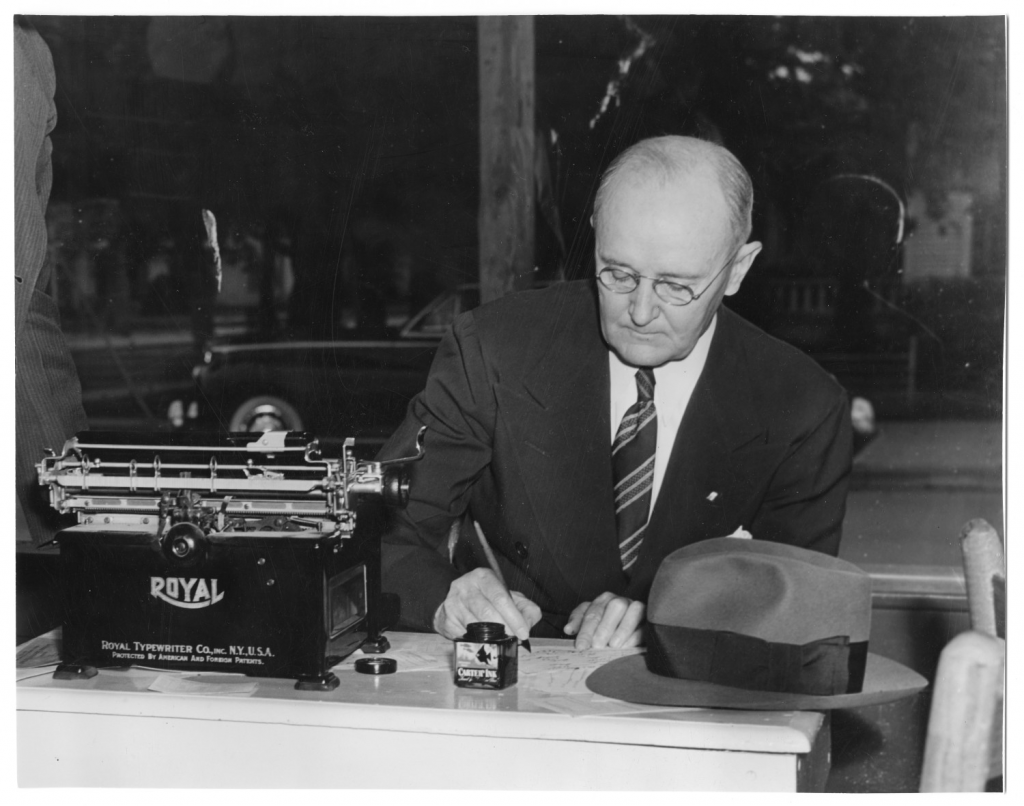

On April 15, 1937, President W.J. McConnell sent a letter to Senator Tom Connally, requesting that North Texas State Teachers College be designated a depository for receiving selected federal government documents. In his letter he stated that “[NTSTC] is a coeducational institution with a long session enrollment of 2,250 and a summer session enrollment of 3,500. The registration is approximately half men and half women.” A copy of the letter was sent to W.D. McFarlane, U.S. House of Representatives, 13th District; and on April 27 President McConnell sent a letter to Senator Morris Sheppard.

McConnell was well aware that another college in Denton, Texas State College for Women (now Texas Woman’s University), had already been designated the 13th District’s federal depository many years previously, but found that situation problematic because the facilities at a college for women were not accessible to the large male population enrolled at NTSTC. Not only would a collection at the co-educational NTSTC be available to both male and female students, it would be housed in a brand new library building that was “said by competent critics to be the second largest and most useful among the institutions of Texas.”

President W. J. McConnell had concluded his fervent plea to Senator Sheppard with an earnest warning: “To look down the line of the future for this large school of men and women with no hope of getting a depository would be discouraging.”

On April 29, Senator Sheppard replied to President McConnell that the Senator’s allotted designation had already been used some years ago to designate Southwestern University (in Georgetown) as a depository, but he promised to make further inquiries about the matter.

On May 6, Superintendent of Documents Alton P. Tisdel wrote back to Senator Sheppard, who then enclosed the Superintendent’s letter in a message to President McConnell. As Sheppard and McConnell must have anticipated, Tisdel reminded everyone that federal law allowed only one designation by each senator, and only one depository library in each congressional district. Because Senator Sheppard had already designated Southwestern University, another request could not be considered. Furthermore, as Tisdel also rather unnecessarily pointed out, there was no vacancy in the 13th District anyway, because another college in Denton, Texas State College for Women, had already been assigned this designation in 1932.

The President’s hopes were dashed, and a decade would pass before North Texas State Teachers College would make another request.

Second Request Is Successful

The 1940s were a crucial time for depository libraries. The distribution of government documents, especially pamphlets, was critical to the war effort, and documents collections in Texas and the rest of the United States were the principal means of bringing this vital information to the public (Texas Library Association, History – the 1940s). As a result, federal depository collections throughout the country were growing.

On December 11, 1947, Texas State College for Women, which had been the 13th District’s depository library since 1932, requested permission to relinquish their depository status after concluding that they did not have sufficient staff to maintain the burgeoning depository collection.

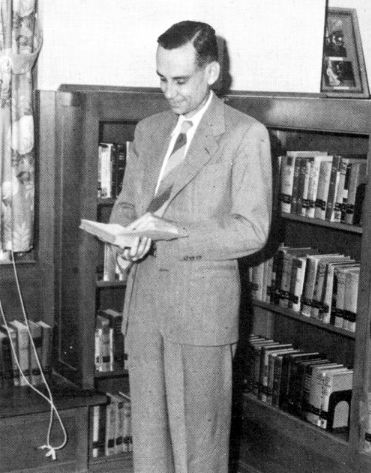

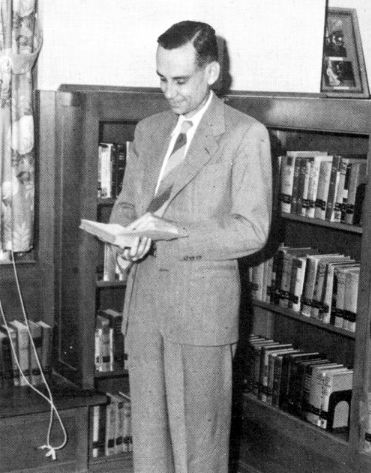

Seizing upon the opportunity provided by this sudden vacancy, on December 18, 1947, NTSTC librarian (and future Poet Laureate of Texas) Arthur Sampley wrote to the Honorable Ed Gossett, the current Representative of the 13th Congressional District, requesting that the NTSTC Library be designated a federal depository library for his District.

Library Director Arthur M. Sampley in the 1948 edition of The Yucca, Yearbook of North Texas State College. University of North Texas Libraries, The Portal to Texas History; crediting UNT Libraries Special Collections.

Dr. Sampley persuasively argued that NTSTC easily met the requirements for depository designation, highlighting the following characteristics:

- 4,668 students

- 265 faculty members

- 14 trained librarians

- 178,000 volumes in the library collection (making it the fourth largest among college and university libraries in Texas)

- A modern, fireproof library

He also emphasized the “large enrollments in the departments of government, economics, science, home economics, and business administration, all of which make much use of government documents,” and pointed out that the NTSTC Library was available to both Denton colleges (which at the time had a combined enrollment of 7,000). In addition, the documents would be available to any citizen of the district who wished to examine them within the library.

The College administration anxiously awaited the Representative’s response.

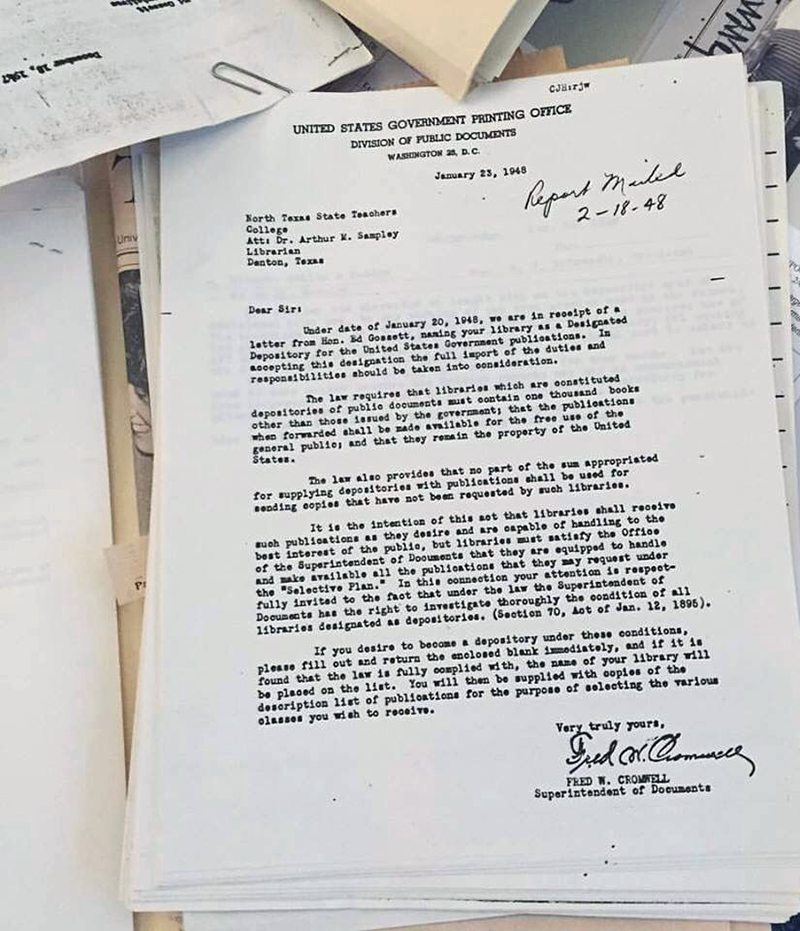

Representative Gossett wrote to Superintendent of Documents Fred W. Cromwell on January 20, 1948, formally requesting the designation of North Texas State Teachers College as a depository library, and on the same day sent a copy of the letter to Dr. Sampley.

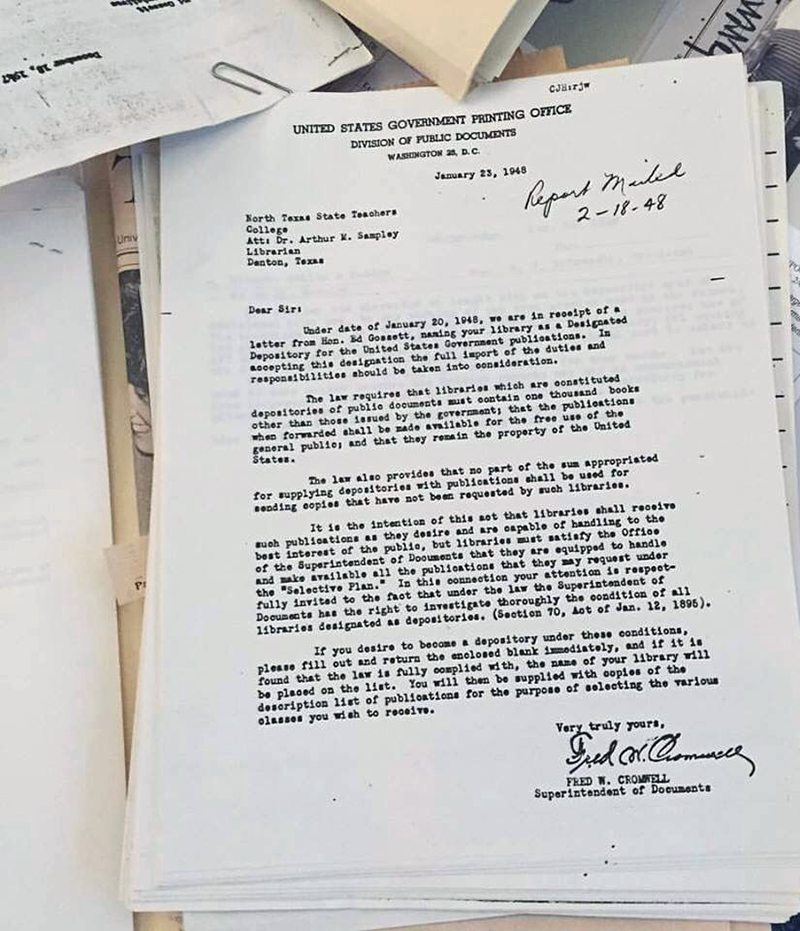

Three days later, on January 23, 1948, the Superintendent of Documents notified Dr. Sampley that NTSTC’s designation as a depository would be approved as long as they accepted the responsibilities and met the requirements of a selective depository library, which were as follows:

- The library must have 1000 books other than those issued by the government.

- The government publications shall be available for the free use of the general public.

- The government publications shall remain the property of the United States government.

- No money appropriated for supplying depositories with publications shall be used for sending copies that have not been requested by such libraries.

- Libraries must satisfy the Office of the Superintendent of Documents that they are equipped to handle and make available all the publications that they may choose under the “selective plan.”

- The Superintendent of Documents has the right to investigate thoroughly the condition of all libraries designated as depositories.

Letter of January 23, 1948 from Superintendent of Documents Fred W. Cromwell designating North Texas State Teachers College as a federal depository library. Crediting Robbie Sittel (@bertiegirl), Instagram, April 13, 2016. https://www.instagram.com/p/BEJMsQDxklF/.

A form was enclosed for Dr. Sampley to complete and return if the North Texas library wished to become a depository under these conditions. Because this form was brief—only four pages—and many depository libraries found themselves in need of further clarification of their responsibilities, the Government Printing Office would periodically supplement this initial list with another list of general instructions.

A Need for Space

In his original 1937 request for depository status, President McConnell had assured Senator Connally that the new Library Building would afford “adequate facilities for all selected documents which would come to us for many years.” Ten years later, he was not so sure that the space would be adequate for the new documents collection.

On January 26, 1948, after conferring with Dr. Sampley, President W.J. McConnell sent a memo to Messrs. Skiles and Dominy (as well as a carbon copy to Dr. Sampley) concerning the library’s need for additional space. He expressed immediate concern about room for the Music Library, and then added that the need for expansion had been made even more urgent by the college’s expectation that any day an announcement from Congressman Gossett would confirm NTSTC’s official designation as a federal government documents depository library.

I’ve Got a Little List

Dr. Sampley’s form was received and accepted, and Superintendent Cromwell notified him on March 4, 1948 that the next step would be to consult the Classified List of U.S. Government Publications—which lists items available for selection by depository libraries—and decide which items NTSTC would receive. Dr. Sampley was to retain one copy of the list and send a duplicate copy to the Government Printing Office within 30 days. He was also warned not to “fold or roll the book.”

The following limits were placed on item selections:

- Although the library’s official date of entry into the depository system was January 20, the library would only begin receiving books published after the list was received in Washington.

- Congressional appropriations for the depository program are limited, so depositories are encouraged to select only items that patrons are likely to use.

- A library may amend its selection by adding or dropping selections at any time.

- Only entire series can be selected; a request for part of a series will not be accepted.

- Only one copy of each publication would be furnished to a library.

On March 30, 1948, Dr. Sampley returned the Classified List to GPO with the items selected that NTSTC wished to receive.

Mission Accomplished

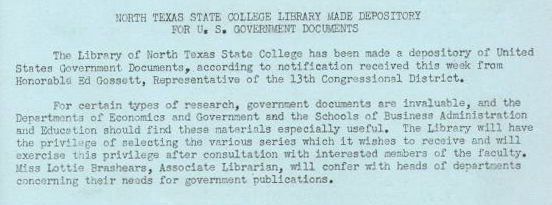

On March 6, 1948, Representative Gossett forwarded to President McConnell the Superintendent’s letter advising of the designation of NTSC as a U.S. government depository, and also congratulated the President on the college’s selection. In a postscript he agreed with the President’s suggestion that an announcement of this wonderful news should appear in the library newsletter.

On March 22, 1948, Dr. Sampley thanked Representative Gossett for his efforts in securing NTSC’s designation as a depository, and also included a copy of the library’s newsletter containing an announcement of the news:

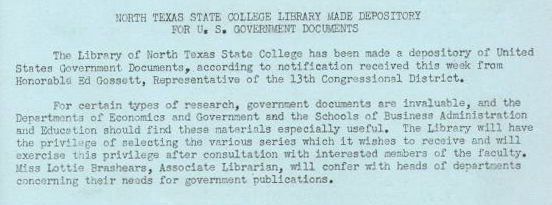

“North Texas State College Library Made Depository for U.S. Government Documents,” NTSTC Books 9, no. 11 (1947-1948): 1

In the fall of 1948, Miss Pauline Ward was hired as the first Documents Librarian at North Texas. She would be succeeded by a long-run of talented and innovative librarians and coordinators who have assisted in establishing UNT’s reputation in the government documents community.

Government Documents Librarian Pauline Ward in the 1951 edition of The Yucca, Yearbook of North Texas State College. University of North Texas Libraries, The Portal to Texas History; crediting UNT Libraries Special Collections.

Additional Instructions from GPO

On October 25, 1948, the NTSTC Library received their first list of general instructions from GPO (not counting the four-page form the library had already filled out). These instructions included the following stipulations:

- Discards: No publication supplied to a depository is to be discarded without following certain strict guidelines, therefore depositories are advised to use great care in making their selections.

- Public Access: Depository materials are to be made freely available to the public, either as circulating items or as non-circulating reference materials.

- Location: Depository materials should be treated with the same care as other library materials, but do not need to be kept in a separate collection.

- SuDoc Numbers: Use of the Superintendent of Documents (SuDocs) Classification System is not mandatory for depository materials, and libraries should weigh it carefully against other schemes before adopting it.

- Reference Materials: Many federal government publications would make a valuable addition to the library’s reference room collection.

- Periodicals: Many government periodicals are quite important and can form a valuable addition to the library’s periodical collection rather than being shelved in a separate location.

- Pamphlets: If the library keeps pamphlets and similar ephemera in a vertical file, government document pamphlets may also be kept there as long as they are kept permanently.

- Binding: Many documents arrive unbound or in paper covers. These should be processed as needed by the library’s own binding program.

- Multiple copies: Libraries are not required to purchase second copies of government documents just to keep them in a separate collection, but are encouraged to buy multiple copies of heavily used items.

- Lost or Damaged Items: Government documents that are lost or damaged should be subject to the same replacement policy as other library materials.

These instructions reflect the general principle that government documents should be used, not merely stored.

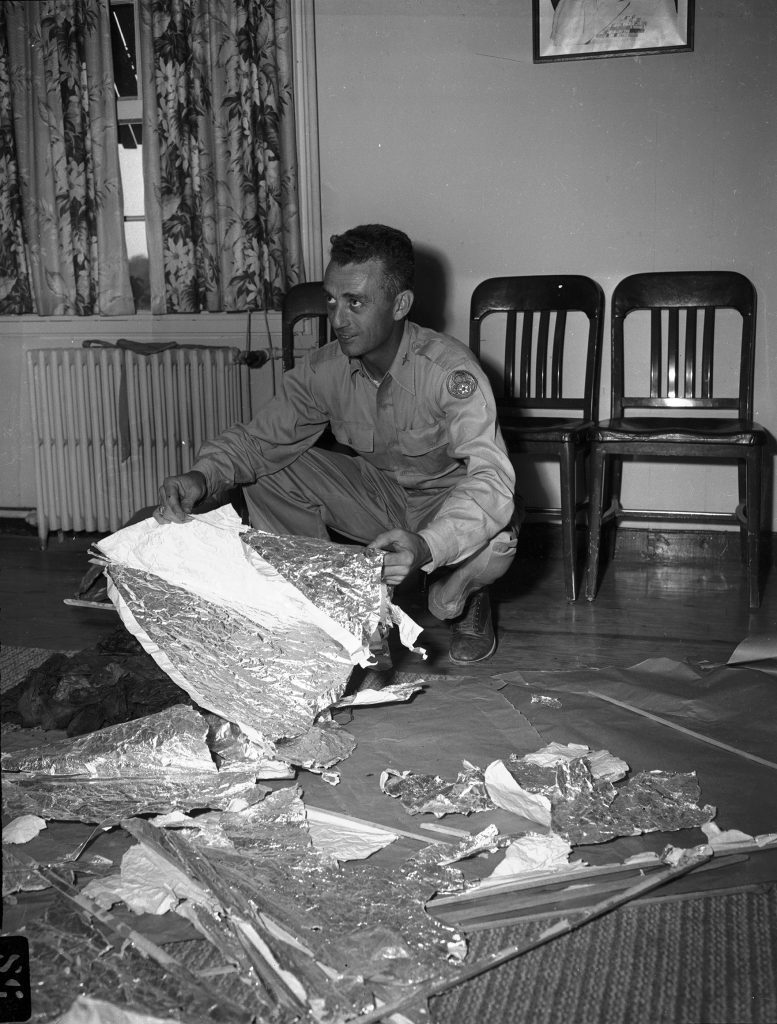

Our First Recall

Shortly after these instructions were received, NTSTC received their first recall notice. They were asked to return a publication that had been distributed the previous month, entitled Logistics in World War II: Final Report of the Army Service Forces.

There was no explanation offered for why this particular item had been recalled, but there are several reasons why a document might be recalled, including the following:

- The item contains information that is perceived as a threat to national security

- The item contains incorrect or misleading information

- The item contains personal or sensitive information

- The item is defective in some way

Depending on the reason for the withdrawal, the instructions may ask the depository library to return the item to GPO, destroy it, or hold it until further instructions have been received. NTSTC was asked to return this item to GPO.

One Year Later

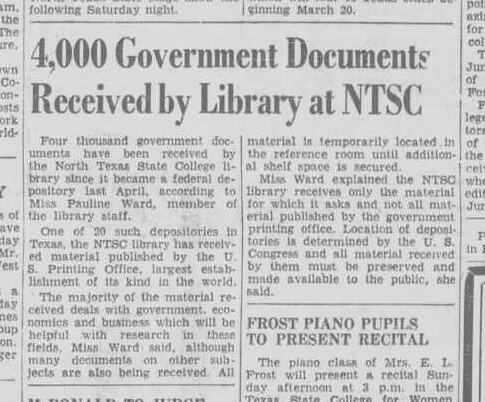

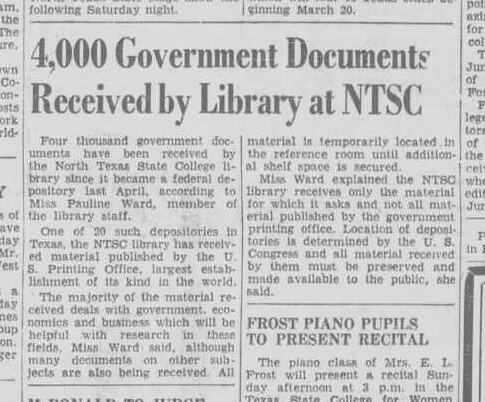

“4.000 Government Documents Received by NTSTC,” Denton Record-Chronicle (Denton, Tex.), March 6, 1949.

A year after NTSTC attained depository status, the Denton Record-Chronicle published an update on NTSTC’s depository holdings, reporting that the library had received 4,000 federal depository publications. Many of these provided information related to government, economics, and business.

Miss Pauline Ward, Documents Librarian, stated that the burgeoning collection would be temporarily located in the Reference Room until additional shelf space could be secured. That “temporary” location was to last 23 years.

A New Documents Librarian

Velma Lee Cathey, as portrayed in North Texas State College, The Yucca, (Denton, Texas: 1951), p. 244, UNT Digital Library, digital.library.unt.edu; crediting UNT Libraries Special Collections. https://digital.library.unt.edu/ark:/67531/metapth61020/m1/259/ (Accessed on April 25, 2023).

In 1953, Pauline Ward decided to marry and move out of Denton. Velma Lee Cathey, who had moved from the History Department to the Library in 1950, became Documents Librarian on a part-time basis while continuing her other Library cataloging duties. Dr. Sampley stipulated that Ms. Cathey was to take a crash course in documents librarianship on her own time, and she agreed. In six weeks, under the tutelage of Pauline Ward, Velma Cathey worked through every problem in the University of Illinois course in U.S. government publications and read the complete United States Government Publications by Boyd and Ripps, the standard textbook on the subject.

By 1955, the Library was allowed to add more staff, and Ms. Cathey became a full-time Documents Librarian. She made the most of her training in government publications, gathering the government documents into the basement of the old Library Building (what is now Sycamore Hall) and beginning a government publications card catalog with four trays, eventually expanding it to well over 300 trays. (This card catalog is still partially in use, and can be seen in the Collaboration and Learning Commons (CLC) in Sycamore Library.

Griffith, Bobby G. (@bg577), 2018, “Day 2: Local bookstore or library.” Instagram, Oct. 2, 2018. https://www.instagram.com/p/BocvOaOHQOW/

Ms. Cathey was responsible for establishing many of the systems, including cataloging of documents, which allow the department to function efficiently and to provide ready access to the government materials. During her tenure as Documents Librarian, she continued to grow the documents program and played an active role in library associations, librarian training, and in academic discourse. At the time of her retirement in 1974, Mrs. Cathey was Assistant Director for Collections.

We Move to the Third Floor of Willis Library

Portrait of A.M. Willis, Jr. sitting in front of Willis Library, from Amanda Montgomery, “A.M. Willis, Jr.,” 125 Year Archival Retrospective (blog), August 14, 2016, https://blogs.library.unt.edu/unt125/2016/08/14/willis/ (Accessed April 26, 2023).

A new library building was constructed in 1969 and officially opened in the summer of 1971. Originally known simply as “the Library,” the building was eventually renamed the Willis Library in 1978 in honor of regent A.M. Willis, Jr. The Government Documents Department was finally able to be moved to more spacious quarters on the 3rd floor of the new building, remaining there until the summer of 2014. At the time of the move, the Library became a subject division library with five divisions: Humanities, Social Sciences, Music, Science, and Library Science. The Government Documents collection was included within the Social Sciences Division.

Damron Dennis Becomes Documents Librarian

Photo of Damron S. Dennis, collection of Sycamore Library.

On September 1, 1970, Ms. Damron S. Dennis joined the Documents staff as Assistant Documents Librarian. At the time the library materials were moved from the old to the new (future Willis) library, Mrs. Dennis and the Documents Cataloger, Mary Lou McGalliard, became Assistant Social Science Librarians, and Velma Lee Cathey was promoted to Assistant Director for Collection Services. When the materials were moved to the new library, Mrs. Dennis supervised the moving of the Documents Collection, while Ms. Cathey supervised the entire library move.

In 1972, Ms. McGalliard left to become head of Technical Services at Yakima Valley Regional Library, and Mrs. Dennis became Documents Librarian. Shortly after this Melody S. Kelly, who had been employed as a Purchasing Clerk from 1971 to 1972 while she was a student at North Texas State University (NTSU, as the school was called from 1961 to 1988), was appointed as Assistant Social Sciences Librarian. One of her duties was the cataloging of government publications.

In May 1974, Velma Lee Cathey retired.

UNT Begins Receiving Microfiche

As a cost-cutting and space-saving measure, in March 1977 the Joint Committee on Printing authorized GPO to proceed with a micropublishing program by converting certain titles to microform. During the first year, GPO had converted 4,045 titles to microfiche and had distributed 2,254,377 microfiche to depository libraries, one of which was the NTSU Library. There were many questions raised by the implementation of this program, including questions on availability, coverage, variety of format, and bibliographic control, not to mention possible library support for microfiche reading and printing equipment, which was lacking in many depositories, especially in public libraries. Eventually the initial problems of publishing a large segment of depository materials in a microfiche format and the concerns of depository librarians in housing and using microfiche materials were resolved, and library patrons for the most part came to accept the materials in this format.

Documents Department Gains Its Independence

On May 1, 1981, the Documents Department was removed from the Social Sciences Division and established as a separate administrative unit. In 1984 the maps and posters were returned to the Documents Department from the Maps/Microforms Department (previously the Special Materials Department), where they had been housed since the move ten years earlier.

Melody S. Kelly Becomes Documents Librarian

Melody Kelly in the early 1970s, working in Willis Library. Photo from University of North Texas Libraries, UNT Digital Library, digital.library.unt.edu; crediting UNT Libraries Special Collections. digital.library.unt.edu/ark:/67531/metadc944913/m1/1/ (Accessed April 26, 2023).

In 1983 Damron S. Dennis retired, and Melody S. Kelly became the new Documents Librarian. She continued in this role until August 2001, when she was appointed Assistant Dean of the Libraries. While she was the Documents Librarian she also taught the Government Documents class as an Adjunct Professor in the School of Library and Information Science.

Federal Documents Added to the Online Catalog

In the early 1990s, the Documents Department contracted with Marcive, Inc. for cataloging services. This allowed government documents to be included in the Library’s online public catalog. Prior to this, government documents were only discoverable via the documents card catalog.

We Enter Cyberspace

Our primary mission as a Federal Depository Library remains the same today as it was fifty years ago: Free Public Access. Our clientele, however, has changed dramatically since the advent and popularization of the World Wide Web in the early 1990s.

Through the Internet, we can now provide the whole world with directed access to full-text federal, state, local, foreign, and international government information. Our unique subject guides support the special needs of scholars, teachers, the business community, and the general public. Documents reference specialists can also respond to information requests via an electronic reference form linked to our website.

Now that we are on the Internet, our services are no longer limited geographically to our immediate Congressional District.

Cathy Hartman is Appointed to Depository Library Council

Portrait of Cathy Hartman by Junebug Clark, October 2, 2015; courtesy of University of North Texas Libraries, UNT Digital Library, digital.library.unt.edu; crediting UNT Libraries Special Collections. digital.library.unt.edu/ark:/67531/metadc978798/m1/1/ (Accessed April 19, 2023).

In 2000, Cathy Hartman, UNT’s Documents Librarian and Electronic Resources Coordinator, was appointed to the Depository Library Council, an advisory committee to GPO’s Director and the Superintendent of Documents, and later served as chair.

Cathy had joined the UNT Documents Department in the mid-1990s, where she launched several digital preservation initiatives that led to partnerships with the GPO and ultimately the development of UNT’s Digital Libraries Division. Cathy also served as the Associate Dean and Interim Dean for the UNT Libraries before retiring in 2018.

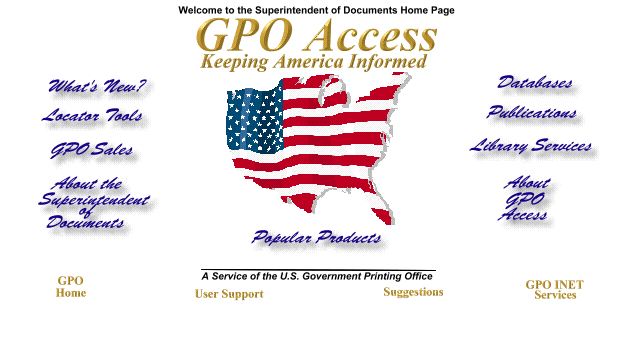

UNT Is Designated a GPO Access Gateway Library

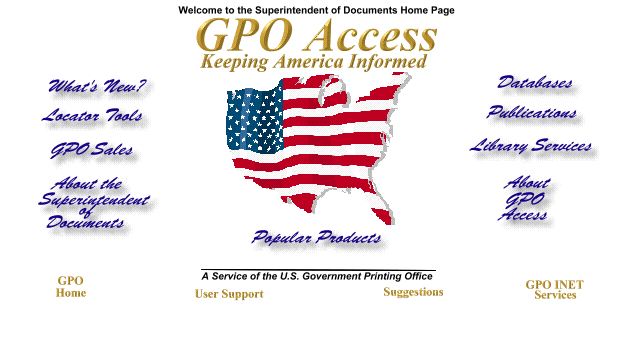

On June 8, 1993, Congress passed the GPO Electronic Information Access Enhancement Act (Public Law 103-40), which expanded GPO’s mission to provide electronic access to Federal Government information. A year later, GPO launched GPO Access, a website that was America’s main source for online government information online for more than 15 years. One of the few information systems established by law, it provided reliable, timely access to official information from all three branches of the Federal Government

In 1994, our Depository was designated a GPO Access electronic Gateway by the U.S. Government Printing Office (GPO). Originally GPO Access was only available to the public by subscription, but was free to depository libraries. In order to maximize free public availability of the resources on GPO Access, federal depository portals, called “electronic Gateways,” provided customized search interfaces adapted to meet the needs of their clients. These electronic Gateways quickly became an effective medium for developing new and innovative ways to make use of the important public resources available through GPO Access.

As a GPO Access Gateway Library, UNT was one of the first depositories to provide access to electronic government information, and as the only GPO Access Gateway Library in Texas, we began to serve a clientele that is truly global.

Eventually technological evolution of both the public’s Internet capabilities and the capacity of the GPO Access system eliminated many of these original needs, so GPO ended its formal support for the Gateway Project on September 30, 2000. By March 2012, GPO Access itself was sunsetted and replaced by FDSys, which was in turn replaced by GovInfo.

We Join the FDLP Content Partnerships Program

In the late 1990’s, online U.S. government information was appearing and disappearing at a rapid pace. Foreseeing the potential preservation problems created by federal agencies’ ventures into electronic publishing, we became the second depository library in the nation to join the Federal Depository Library Program Content Partnerships Program. This program attempts to ensure permanent public access to electronic federal information.

In August 1997 we signed a memorandum of understanding (MoU) with GPO designating the UNT Depository Library to preserve the website of the newly defunct Advisory Commission on Intergovernmental Relations (ACIR).

In 2001, as designated host of the permanent online collection of the ACIR, we received a grant to finance the creation of electronic copies of well-known ACIR print publications such as Significant Features of Fiscal Federalism. Electronic copies of older ACIR reports are now available to scholars throughout the world via our website.

We’ve since expanded our Content Partnership with the federal government to include dozens of other defunct federal agency Web sites. This electronic repository, designated the CyberCemetery, and provides permanent public access to the websites and publications of defunct U.S. government agencies and commissions.

This partnership between UNT and GPO later expanded to include the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA). In recognition of our work in this area, the UNT Libraries were designated an Affiliated Archive of the National Archives and Records Administration in 2006. Under this agreement, the UNT Libraries will continue to preserve and provide access to the records of defunct government Web sites, while NARA will legally accession the records as part of the Archives of the United States and will join the UNT Libraries and the GPO in ensuring the preservation of these valuable records. We are currently the only non-military educational institution to be designated an Affiliated Archive.

We Create More Digital Collections

Over the years we have created many more digital collections that have benefited the public.

The Congressional Research Service (CRS) serves as nonpartisan shared staff to congressional committees and members of Congress, providing them reports on various topics. The CRS Reports archive provides integrated, searchable access to hundreds of full-text Congressional Research Service reports that were previously only available to members of Congress or posted on a variety of sites scattered across the Web.

Our Federal Newsmaps collection provides digital access to Newsmaps produced by the U.S. War Department during World War II. They usually feature maps displaying the theaters of conflict and often include narrative descriptions of war-related events. Some feature photographic essays or poster-like designs on themes such as enemy insignias, demobilization, and farm loans.

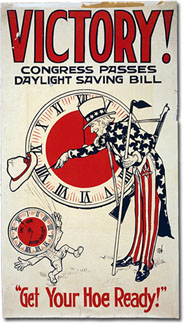

Our collection of over 600 World War Posters was digitized shortly before being transferred to the Rare Book and Texana Collections, where it resided briefly before being returned to the Documents Department. This collection is particularly strong in World War I French and American and World War II American “home front” posters, covering topics such as war bonds, rationing, enlistment, security, and morale, and featuring the work of popular artists such as Norman Rockwell, Theodore Geisel (better known as Dr. Seuss), and Boris Artzybasheff.

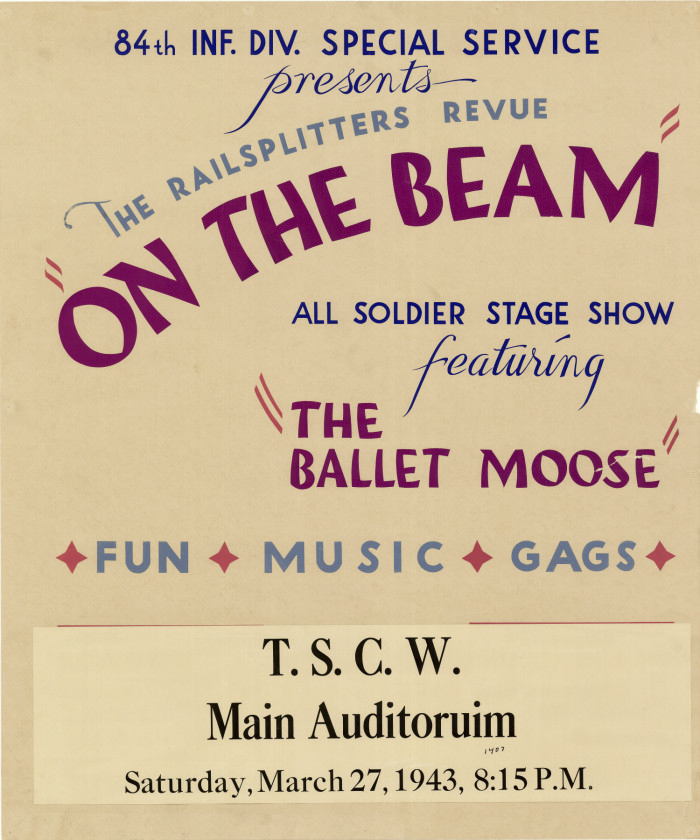

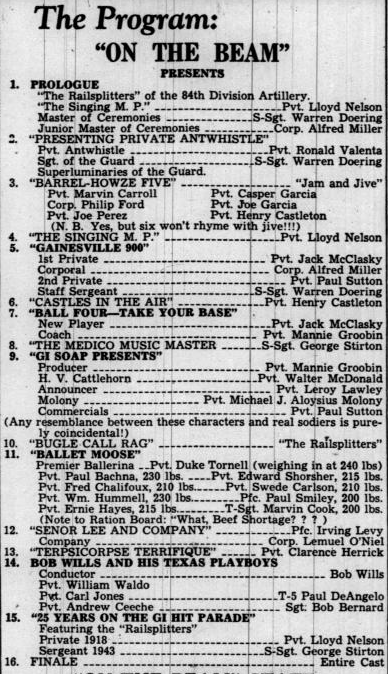

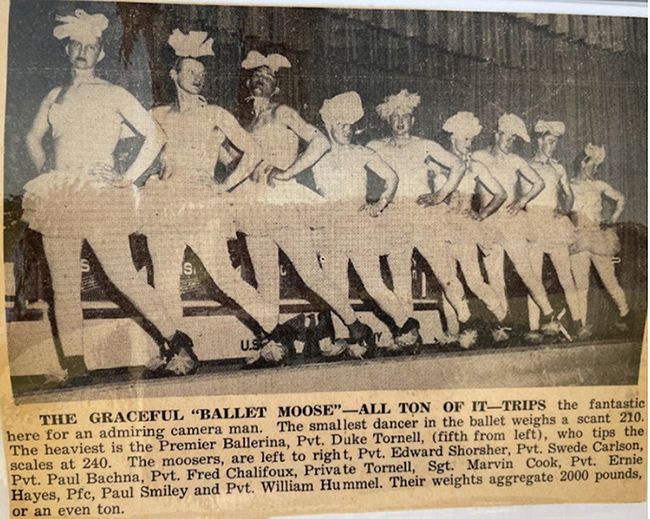

These are scripts and scores of shows that were performed by soldiers for their fellow soldiers during World War II, developed by the Special Services Division of the American Services Forces as a morale-building tool. The Soldier Shows “Blueprint Specials” provided soldiers with all the resources they needed to stage an original, Broadway-style musical. They were made available online in December 2022.

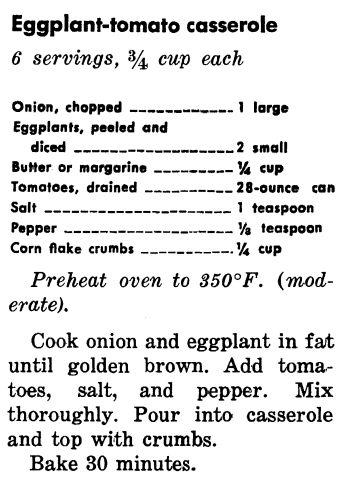

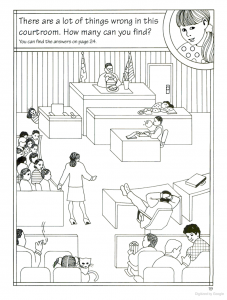

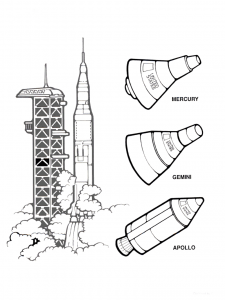

These are a selection of comic books from the UNT Libraries government comics collection. The collection includes comic books produced or commissioned by the U.S. government, government publications with cartoon-style illustrations, and government publications about comics, such as drawing manuals and congressional hearings. This collection was made available online in December 2022.

We Initiate the Texas Agency Partnership Program

Our experience with Federal Partnerships and digitization projects has served us so well that we have applied the concept to the state level.

In 2000, we initiated the first Texas Agency Content Partnership through a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU). This MOU is modeled on the GPO Content Partnership agreement, and our new agreement with the Texas Secretary of State established this collection to ensure permanent storage and public access to the non-current electronic files of the Texas state government publication, the Texas Register.

The most current issue of the Texas Register is first posted on the Texas Register website, where they maintain access to the most current six (6) months’ issues. The University of North Texas Libraries provides free access to all issues of the Texas Register beginning with Volume 1, No. 1 (January 6, 1976) up to within a week of the most currently released issue.

In 2003, we received a grant to digitize the first ten volumes of Gammel’s The Laws of Texas and also debuted as a Texas Electronic Depository Library.

Although H.P.N. Gammel’s editions of The Laws of Texas (1822-1897) were published over one hundred years ago, they are still one of the most important primary resources for the study of Texas’ complex history during the 19th century. At the time this project was begun, The Laws had never been reprinted, and the set in its entirety had become quite rare and virtually impossible to obtain. Furthermore, the existing sets are fragile and often in poor condition.

Historians, legal professionals, students, and other researchers in the state and elsewhere benefit from the electronic access offered by this project. The complete set of 33 volumes is available, with funding for the first 10 volumes provided by the TexTreasures program, which provides grants designed to help libraries make their special collections more accessible for the people of Texas and beyond.

Our Texas Laws and Resolutions Archive makes available online all bills, joint resolutions, and concurrent resolutions that have been passed by the Texas Legislature from the 78th Legislative Session to the present, including those that were vetoed by the Governor.

The University of North Texas Libraries and the Office of the Texas Secretary of State, in a partnership arrangement, established this site to ensure permanent storage and public access to the non-current electronic files of the Texas Laws and Resolutions, beginning with the 78th Legislative Session.

Our historical collection of Texas Soil Surveys puts online all Texas county and reconnaissance soil surveys completed prior to 1950. These surveys demonstrate early scientific thought regarding soil identification and use, and the maps contained in them show many cultural features in the landscape, including businesses, churches, schools, gins, mills, and ferries.

We Are One of the Last Three Active Texas Depository Collections

In 2011, the Texas Depository Library Program was severely curtailed and most Texas depository libraries stopped receiving new Texas state publications. Although several libraries in Texas have retained their collections, and staff continue to share their in-depth knowledge of government information, the only currently active Texas state depository collections are the Texas State Library and Archives Commission in Austin, Texas Tech University in Lubbock, and the University of North Texas in Denton.

UNT Wins Depository Library of the Year Award

UNT staff receiving Depository Library of the Year award pictured (left to right): Jen Rowe, Jenne Turner (holding image of Melody Kelly), Bobby Griffith, Robbie Sittel, Betty Monterroso, Davita Vance-Cooks, Suzanne Sears, Martin Halbert, Mary Alice Baish. Photo from collection of Sycamore Library.

In October 2015, the University of Texas Libraries received the Depository Library of the Year Award from the U.S. Government Publishing Office (GPO). The following services and accomplishments were mentioned as factors in winning the award:

“The University of North Texas Libraries offers access to more than six million print and digital materials and innovative programs to its patrons. UNT has worked with GPO for more than two decades in leading the way of digitizing Government documents and preserving online Government information before other libraries began those efforts. GPO is a partner of the UNT Digital Library, which allows the public to find Government information in a digital format. GPO and UNT first partnered in 1997 for “The CyberCemetery,” which preserves and provides access to publications and websites of defunct Government agencies and commissions.”

We Partner with GPO as a Preservation Steward

In February 2020 the UNT Libraries signed a Memorandum of Agreement (MoA) with GPO to become a Preservation Steward.

Preservation Stewards make a commitment to retain specified tangible depository resources for the length of the partnership agreement. They also take on the additional responsibilities for preserving that material. This includes both preventive maintenance and conservation treatments.

As a Preservation Steward, UNT has committed to preserving a number of unique collections, including government comics, cookbooks, and the Statistical Abstract of the United States, among other materials.

Our Future

With the continued support of UNT and the UNT Libraries, our Federal Depository Library—and our collection of Texas state publications—will remain not only a valuable local resource, but also will, through the Internet, serve an expanding global community of scholars.

Do You Want to Know More?

- Join us on Thursday, April 27, 2023 as we celebrate 75 years as a federal depository library. This event will feature an address by Scott Matheson, Superintendent of Documents as well as refreshments, games, giveaways, and highlights from our collections.

When: Thursday, April 27, 2023 at 2 p.m.

Where: Sycamore Library, Sycamore Hall

- Watch an address by Superintendent of Documents Scott Mattheson reviewing our accomplishments over the last 75 years, and peruse an interactive timeline reviewing our history: 75 Years as a Federal Depository Library

- Visit Sycamore Library on the University of North Texas Campus to browse our collections and perhaps check out a few documents!

- If you need assistance with finding or using government information, please visit the Service Desk in the Sycamore Library during regular hours, contact us by phone (940) 565-4745), or send a request online to govinfo@unt.edu.

- If you need extensive, in-depth assistance, we recommend that you E-mail us or call the Sycamore Service Desk at (940) 565-2870 to make an appointment with a member of our staff.

Article by Bobby Griffith, expanded from an article by Melody Kelly.

Benjamin Franklin is credited with first conceiving the idea for a daylight-saving law, which he proposed (perhaps as a joke) in an anonymous and humorously-worded letter to the editor

Benjamin Franklin is credited with first conceiving the idea for a daylight-saving law, which he proposed (perhaps as a joke) in an anonymous and humorously-worded letter to the editor  The National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) has answers to several

The National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) has answers to several